MIXING UP THE MEDICINE: FILM FARM 30TH ANNIVERSARY

@ OTHER CINEMA SAN FRANCISCO SEPT 21 2024

Other Cinema Screening of Film Farm Films

Archive tour with Craig Baldwin September 21, 2024!

CANYON CINEMA SALON, SAN FRANCISCO

vulture & Film Farm Films (by Maïa Cybelle Carpenter & Markus Maicher). Program curated by Brett Kashmere: Continue reading MIXING UP THE MEDICINE: FILM FARM 30TH ANNIVERSARY

Brasil Tour 2023

Hoffman Screenings at Strangloscope Fest, Curitiba Cinematheque, and 1666 Festival, Sao Paulo:

Flower Power and the Language of Animals

Film Farm Brasil

endings at Ribalta Film Festival

Award for endings Ribalta Film Festival, Italy

Archive tour with Craig Baldwin September 21, 2024!

CANYON CINEMA SALON, SAN FRANCISCO

vulture & Film Farm Films (by Maïa Cybelle Carpenter & Markus Maicher). Program curated by Brett Kashmere: Continue reading endings at Ribalta Film Festival

Deep 1 @ Simon Fraser University, B.C. & Ribalta Fest, Italy (Review)

The Gāyatrī mantra of the Ṛigveda sets-up the entire short film: it is the mantra itself that creates the atmosphere of darkness, followed by the first creation: the tree, which contains the identity of darkness as if it were its visible matter…. (see below) “Deep 1” Ribalta Film Fest Review

`Deep 1′ preview

DEEP 1 (2023, 15 min, HDV or 35mm)

Hoffman on `Deep 1′

…more on Hoffman’s films

Stan Brakhage on `passing through/torn formations’

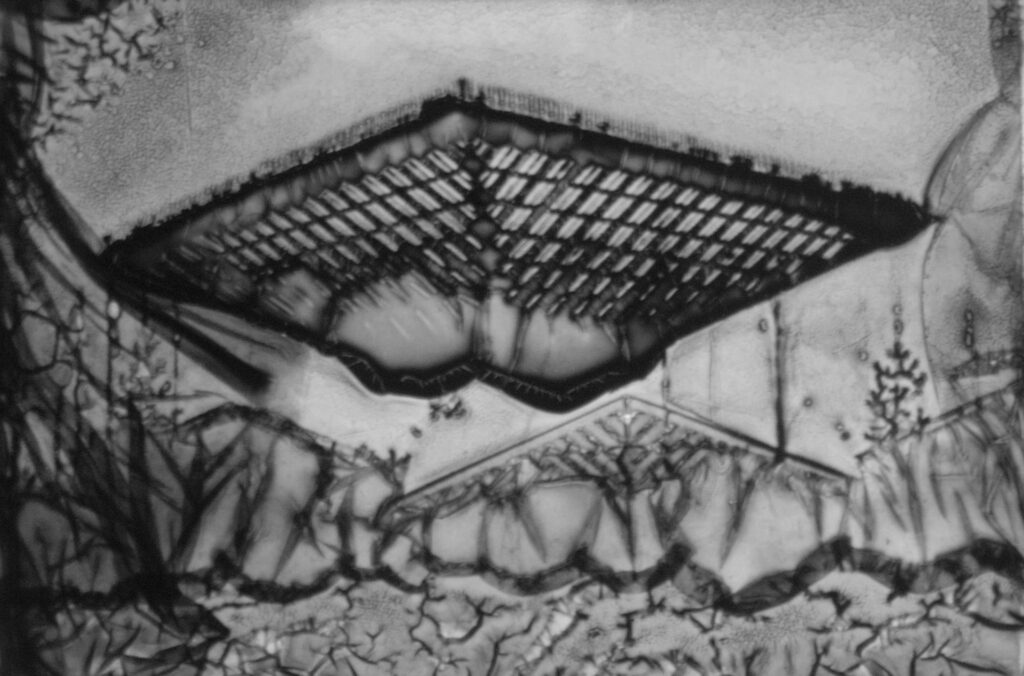

“passing through/torn formations accomplishes a multi-faceted experience for the viewer—it is a poetic document of Family, for instance—but Philip Hoffman’s editing throughout is true to thought process, tracks visual theme as the mind tracks shape, makes melody of noise and words as the mind recalls sound.”

PASSING THROUGH/TORN FORMATIONS (1988)

`passing through/torn formations’ preview

Mike Hoolboom on `passing through/torn formations’

Hoffman’s sixth film in ten years, passing through/torn formations is a generational saga laid over three picture rolls that rejoins in its symphonic montage the broken remnants of a family separated by war, disease, madness and migration. Begun in darkness with an extract from Christopher Dewdney’s Predators of the Adoration, the poet narrates the story of ‘you,’ a child who explores an abandoned limestone quarry….The film’s theme of reconciliation begins with death’s media/tion—and moves its broken signifiers together in the film’s central image, ‘the corner mirror,’ two mirrored rectangles stacked at right angles. This looking glass offers a ‘true reflection,’ not the reversed image of the usual mirror but the objectified stare of the Other. When Rimbaud announces ‘I am another’ he does so in a gesture that unites traveller and teller, confirming his status within the story while continuing to tell it. It is the absence of this distance, this doubling that leads the Czech side of the family to fatality.

complete Cinema Canada review by Mike Hoolboom on `passing through/torn formations’ Continue reading Deep 1 @ Simon Fraser University, B.C. & Ribalta Fest, Italy (Review)

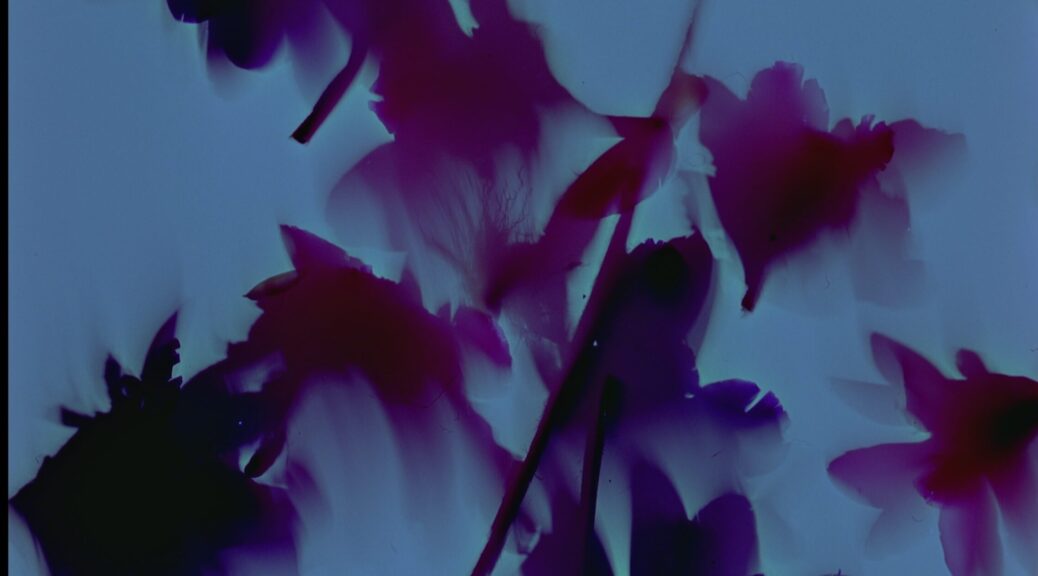

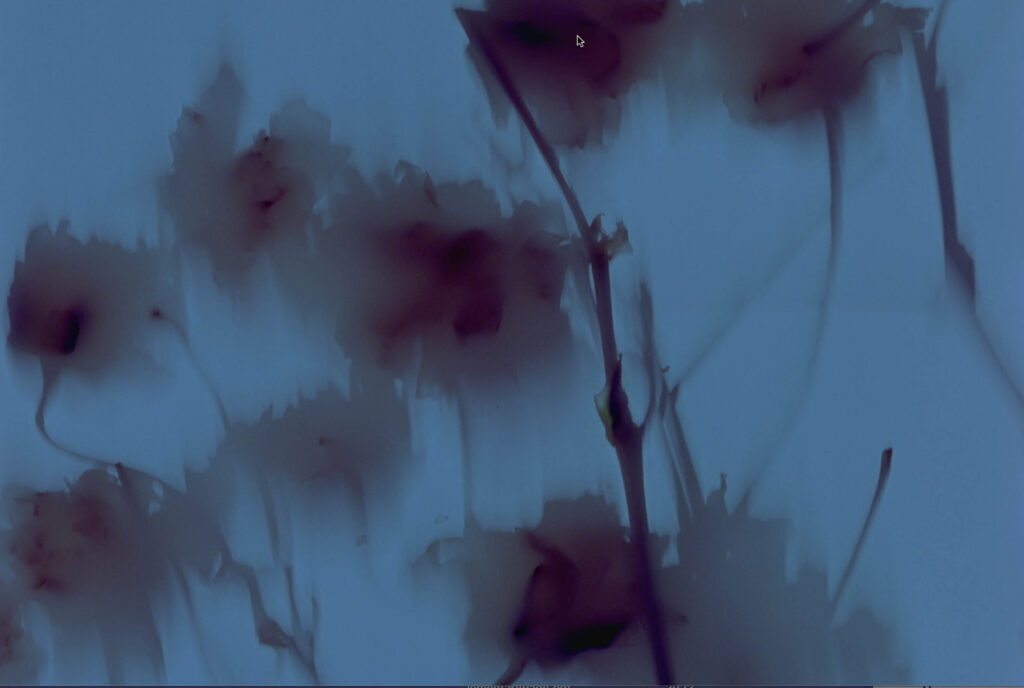

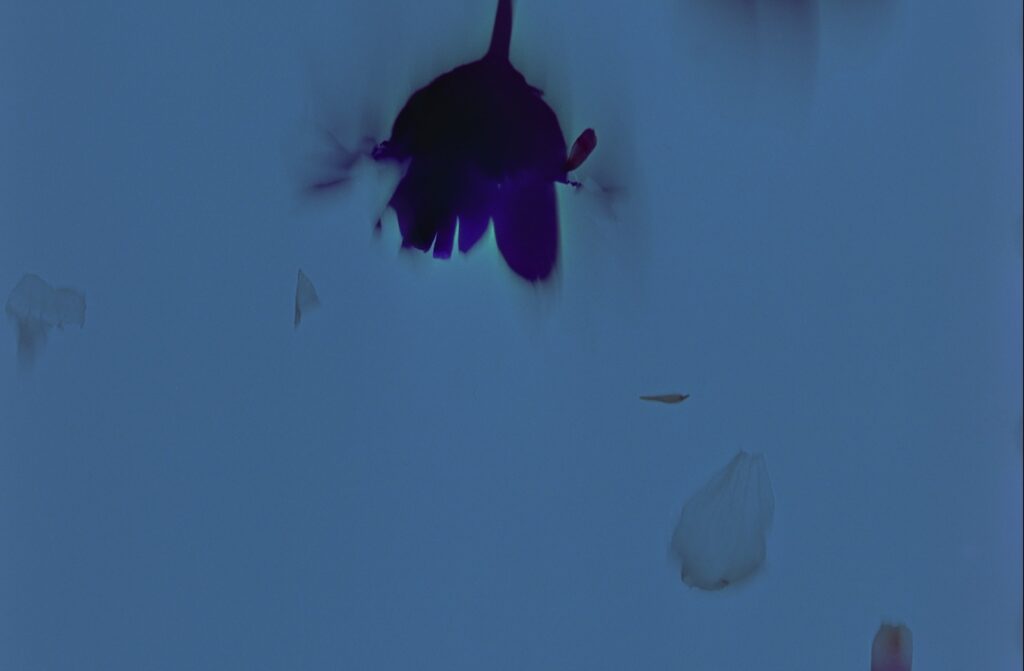

Deep 1 (2023)

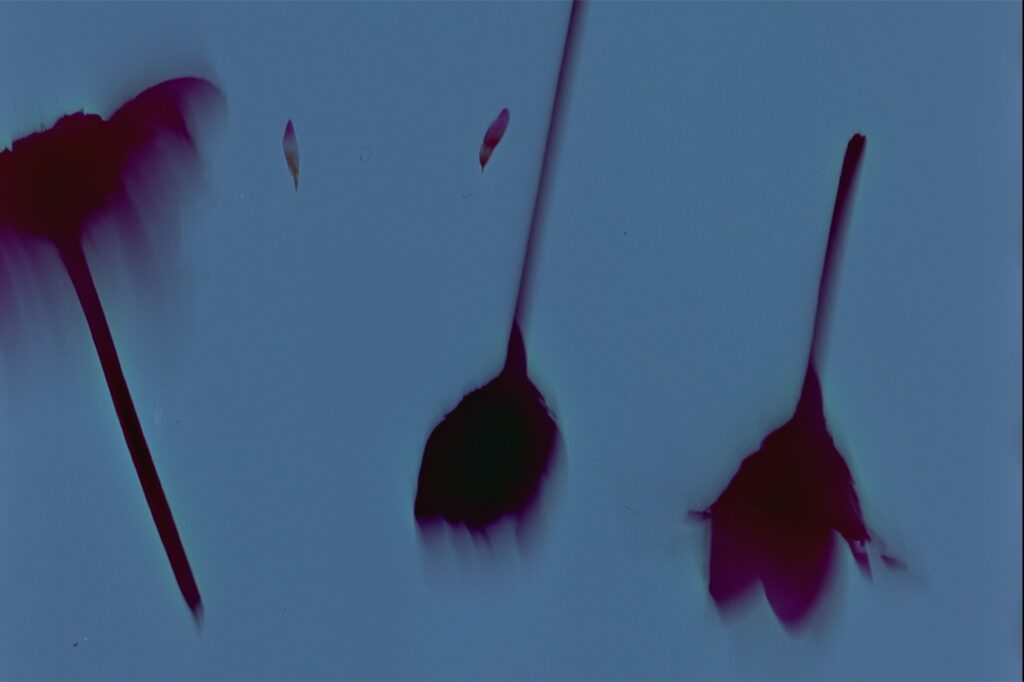

Deep 1 (14:30, 2023)

Filmed over 2 years (2020-2022), at home and away, Deep 1 is a diaristic meditation, flower/plant processed and decayed with hyacinth and lichen extract. Winged and four legged animals, both wild and domestic, traverse the frame marked by a hand-made practice. Filmed in Mount Forest, Ontario and Dawson City, Yukon. *available on digital & on 35mm

Analogica Festival, Bolzano, Italy 2024 Playhouse Theatre, Hamilton, Ontario 2024 Prismatic Ground Film Festival New York 2024 Shapeshifter Cinema, Oakland 2024 Simon Fraser University, Vancouver 2024 Adhoc, Innis College Toronto, 2024 Revolutions Per Minute Film Festival, Harvard U, Boston 2024 Ann Arbor Film Festival 2023, USA; Jury Award Ribalta Experimental Film Festival 2023, Italy La Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión (EICTV) 2023, Cuba Strangloscope Festival, Brasil 2023 16mm Film Festival, Mumbai, India 2023

Opening audio passage from a recording of the “Gayatri Mantra” by mentor/friend Rup Chand (Ann Arbor 1979). He told me that his mother suggested he recite the words when he was in fear.

Om Bhur bhuvah svah Tat savitur varenyam Bhargo Devasya dheemahi Dheeyo yonah prachodayaat — The Rigveda (10:16:3)

“Oh manifest and unmanifest, wave and ray of breath, red lotus of insight, transfix us from eye to navel to throat, under canopy of stars spring from soil in an unbroken arc of light that we might immerse ourselves until lit from within like the sun itself.” (translation from Sanskrit by Ravi Shankar)

About looking at things; envisioning a space “where we are not separated from other things.” – R.H. Blyth

“across the window, birds and beasts look unaware of their decay” –Ph

Still Time in Philip Hoffman’s `Deep 1’

by Lucia Ruggieri, Francesco D’Accia, Matteo Ricci (Ribalta Experimental Film Festival, Italy)

Thankyou Federica Foglia for the Italian to English translation!

The Gāyatrī mantra of the Ṛgveda sets-up the entire short film: it is the mantra itself that creates the atmosphere of darkness, followed by the first creation: the tree, which contains the identity of darkness as if it were its visible matter. Continue reading Deep 1 (2023)

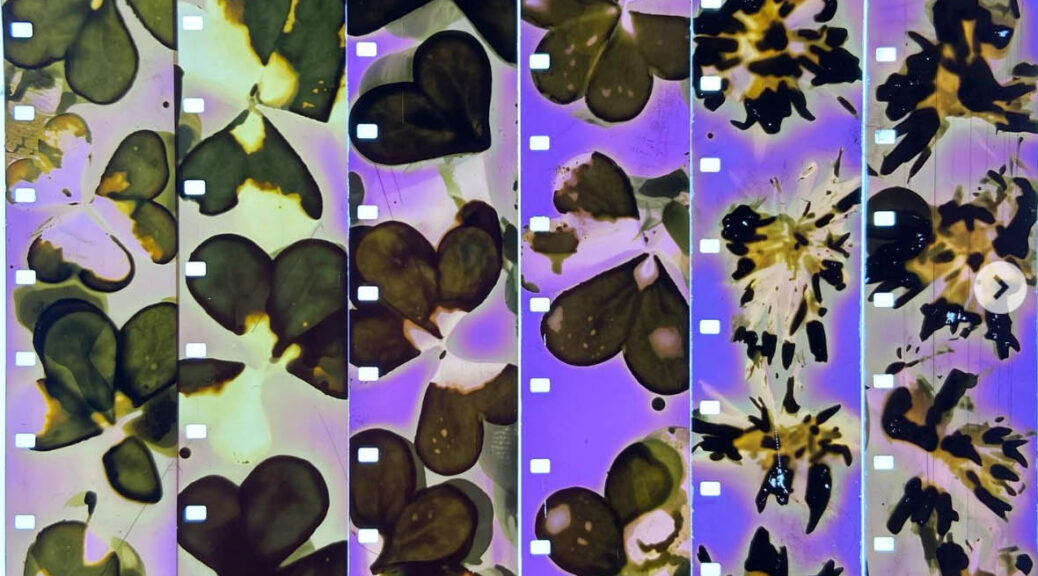

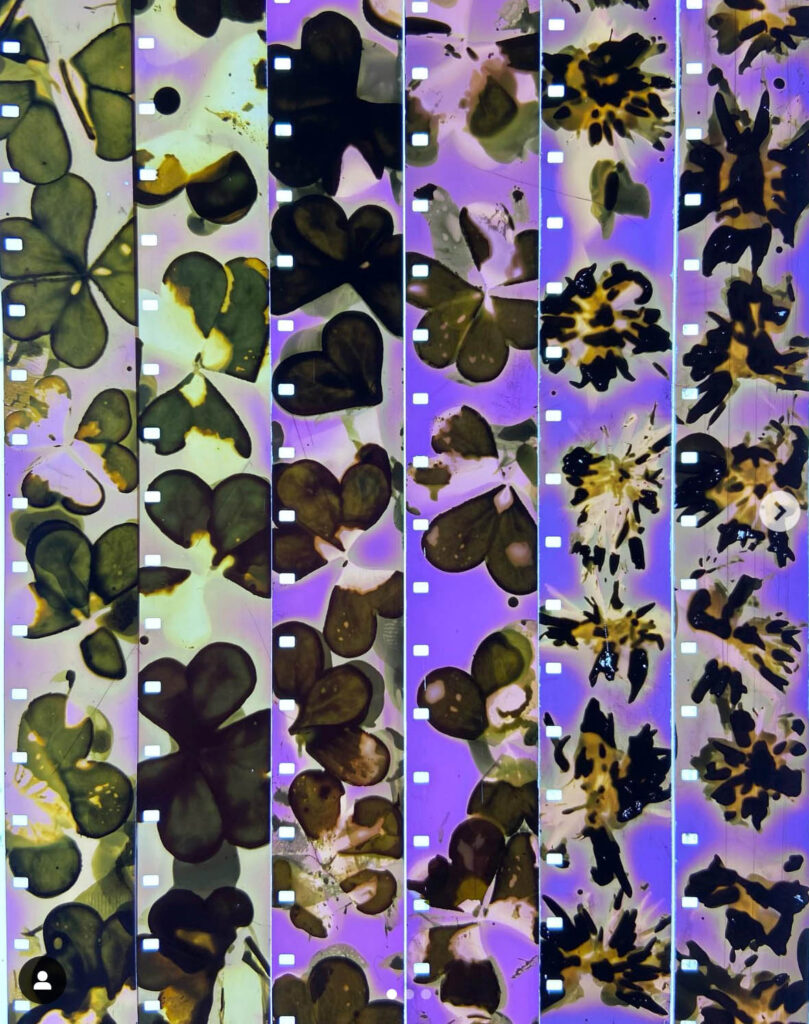

Flowers #1 (2022)

Flowers # 1 (3:18, 2022) By Philip Hoffman & Alexander Granger

This motion picture photogram was made during a 5 hour plunge into the darkroom; a procession of herbs. Séance #3 – Sentir Comme Une Plante

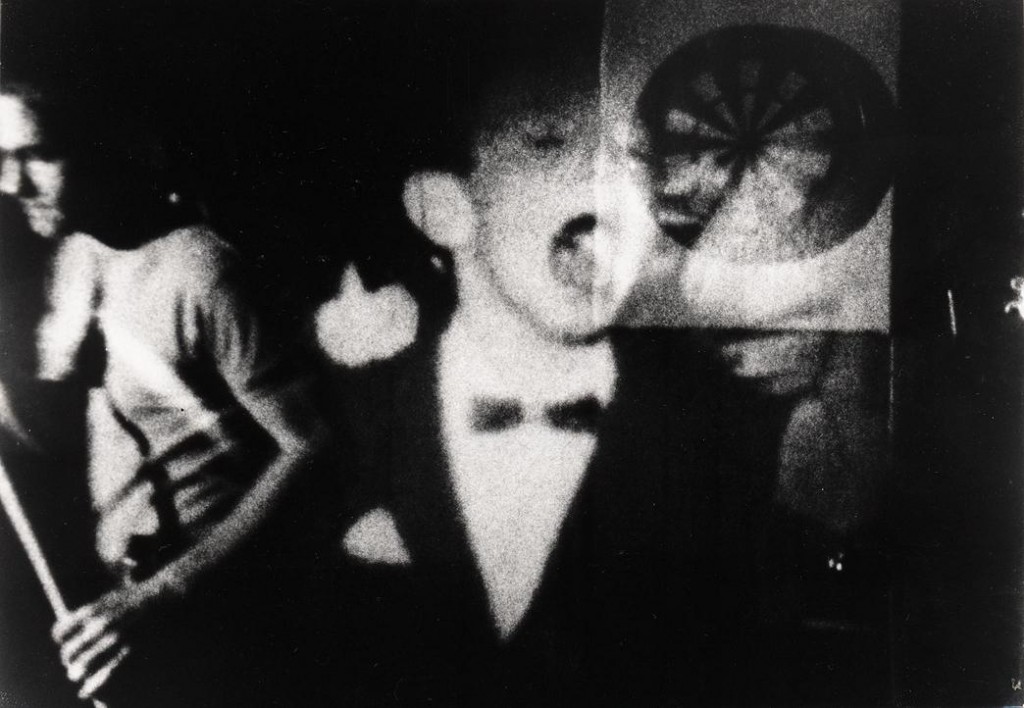

Chimera – Philip Hoffman

“Chimera is Hoffman’s most understated film that explores his two most common themes: death and chaos. And it is perhaps his most immediate film dealing with frozen moments, life transitions and fragments of memory. The shots are in constant movement and it makes the image blurred a good portion of the time; periodically, a readable moment will appear, just briefly, and then the movement continues. It’s a statement in chaos at its most heightened state. The world is blurry with only snatches of clarity—it’s moving fast with only glimpses of calm. You never know exactly where you are or what is going on, except for fleeting moments.”

From Impakt

Flowers #3 (Kissed by the Sun)

Flowers #3 (Kissed by the Sun) 10 min., 35mm photogram to HDV, Sil., 2023. By Philip Hoffman in collaboration with Alexander Granger and Jason O’Hara

These motion picture photograms were initiated through a five hour plunge into the darkroom;

remembering the Galician celebration of flowers on the road in Baiona, near Vigo in 2019, here too we made a floral carpet of photograms. –P.Hoffman

A Procession of herbs “emerge in all their structures, colors and epidermis.

The motion picture itself becomes a plant which delicately stretches petioles and petals.” – Séance #3-Sentir Comme une Plante, Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle, Paris.

“From Film Lab to Film Farm” by Kim Knowles

EXCERPT from Film Lab to Film Farm by Kim Knowles (Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices, Palgrave MacMillan, 2021.)

Over the next few days, our world reduces to the contours of this barn and the surrounding fields, but I feel my mind expanding into new terrain. We are taught how to operate the Bolex camera, how to hand-process as negative and reversal with traditional chemistry, as well as eco-friendly formulas with local flowers and plants. We plunge ourselves into the colorful world of tinting and toning, the handmade and largely unpredictable processes that define such films as Jennifer Reeves’ We Are Going Home (1998), Eve Heller’s Behind This Soft Eclipse (2004) and Penny McCann’s Crashing Skies (2002). We experiment with solarization in the dark room, each of us secretly hoping to get results as striking as Chris Chong’s Minus (1999), an uncut stream of superimposed movements on a single roll of film that were apparently produced in one sleepless night at the barn. read more

CFMDC Panel on Kim Knowles book “Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices” here

Film Farm 25th Anniversary 2019

Exhibition curated by Michelle Lovegrove Thomson

Kim Knowles talks about Film Farm at Tiff Bell Lightbox 2019; and Q & A

Screenings Curated by Chris Kennedy

If there is life in the BARN: it will survive. Philip Hoffman interviewed by James Holcolme

Can you talk a little about the history of the land and buildings before they became a rural lab? Can you paint a textual picture of the landscape over the seasons and how the equipment is bedded down for the winter – what do you have to do to keep quite complex machines working and functional?

I got the property in the early 1990’s, with my partner at that time Marian McMahon, with the idea of creating a kind of school for image-making. The old stone house was built by Henry Chilton in the 1880’s, and had been used for farming ever since. The farm is approximately 50 acres, and some of it is used by my neighbours for farming purposes, in exchange for various things over the years… Erwin dug the pond and built a foundation for an extension to the house. Tom plows my lane and gives me a freezer of meat every year from his grass fed animals that graze on the land. We started the workshop in 1994 with Rob Butterworth, Tracy German and Marian McMahon, and at the time my neighbour had cows in the bottom of the barn, so we had mooing sounds echoing through the barn while we screened films! The old barn, built probably in the 1920’s is an old Mennonite constructed structure, held together solely by wooden pegs. Over the years my partner, Janine Marchessault, and I have had to maintain the barn by having our friend Jon Radojkovic, who’s an expert in timber frame barns, help to keep it standing, as the barn shifts. In 2007 he did a major repair, as the barn was shifting quickly. My neighbour Wayne put some cement posts at the back of the barn and Jon tightened some of the major beams using a permanent winching system, with thick wire, and replaced some beams by jacking the barn up…the jacking is done over a few months, raising the barn a fraction of an inch every week. So the barn is in a constant state of repair. Every winter the animals, the wind and snow take over the barn. We cover everything in tarp and hope the machines start up again in the spring!

Read the complete interview here.