Peter Greenaway

28 St Peter’s Grove

London W6

January 24th 1984

Monique Belanger

Arts Awards Service

Canada Council, Ottawa

Dear Ms Belanger,

I met Phil Hoffman at the 1984 Grierson Seminar. His films were a breath of fresh air amidst so much conventional material. His films blithely side-stepped the orthodoxies so taken for granted by those who believe documentary cinema is an educational rostrum, is about questions of balance, is essentially a dissertation on something described as ‘truth.’ Meeting him in the context of his films backed up my impressions of his aims and abilities. His work is an encouragement to those who want to use autobiography as subject matter, personal vision as a trademark, and show how small resources can be a positive virtue.

It was Phil’s suggestion in London several months later that he would like to be some sort of witness to the feature production of the film Zed and Two Noughts in Rotterdam in the Spring of this year—which I am certainly agreeable to—though I will not hide the fact that I believe, as a filmmaker with a personal vision, he is well past the apprenticeship stage. What he needs now is opportunities, encouragement and experience. Since his method is to work with a camera as a constant companion, I would wish he could be encouraged to make a modest film whilst he is in Rotterdam and London, certainly to be encouraged to shoot some two or three thousand feet of 16mm. The desirability of his presenting a script before hand, as far as I can see, is not necessary, considering his work method. In fact, I think it ought to be a condition of his association with the Zed and Two Noughts project that he shoot on his own on any subject whatsoever.

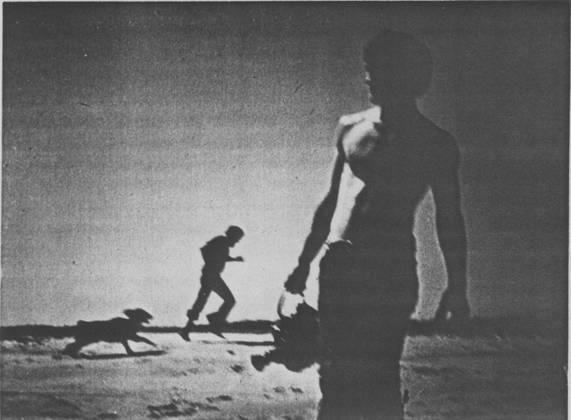

Most of the relevant detail of the production of Zed and Two Noughts Phil has already mentioned. It is perhaps not so strange a co-production, as seen from a British point of view, but nonetheless will present a nicely complex mixture of finance, production, cast and crew that aptly mirrors the complexity of the film’s structure and content—the ambivalent diversity of species and purpose—of beasts and men—both sides of the cages in a zoo. Phil has volunteered not just to stand by and observe but to offer practical help which will always be useful on such a modestly budgeted, ambitious film.

If he (and you) believe that he (and you) can profit by his experience with the production, then I am certainly happy to invite him. If there is anything else you would like to know, I am sure I can help, though I would be obliged, as I am sure you would understand, to keep bureaucracy to a minimum. The production of a feature film is very time-consuming and demanding.

Here’s hoping that you can agree to Phil’s participation.

Yours sincerely,

Peter Greenaway