(2001, 55 minutes, 16mm)

In the documentary film What these ashes wanted Hoffman arranges the jagged bits of life he shared with writer Marian McMahon. Her early death in 1996 provoked this essay on mortality. Hoffman’s goal: “to illuminate the conditions of her death… the mystery of her life and the reason why, at the instant of her passage, I felt peace with her leaving… a feeling I no longer hold.” Using painterly swatches of sunflowers, hand-processed film, found sound recordings, the “antiseptic fictions” of doctors and other mortal icons, Hoffman takes us on journeys to London, Helsinki and Egypt. Pondering morbidity in its many forms, Hoffman discloses an early photographic assignment involving his deceased grand-father, a failed suicide, and his own personal numerology of death centering on the number seventeen. Through these and other memories, he develops a soul-searching vocabulary of love for one whose journey continues into the beyond. ‘If you had to make up your own ritual for death, what would it be? Would it be private or shared?’ asked his partner, Marian. Hoffman’s answer is this beautiful document. (San Francisco International Festival Catalogue, 2002)

In the documentary film What these ashes wanted Hoffman arranges the jagged bits of life he shared with writer Marian McMahon. Her early death in 1996 provoked this essay on mortality. Hoffman’s goal: “to illuminate the conditions of her death… the mystery of her life and the reason why, at the instant of her passage, I felt peace with her leaving… a feeling I no longer hold.” Using painterly swatches of sunflowers, hand-processed film, found sound recordings, the “antiseptic fictions” of doctors and other mortal icons, Hoffman takes us on journeys to London, Helsinki and Egypt. Pondering morbidity in its many forms, Hoffman discloses an early photographic assignment involving his deceased grand-father, a failed suicide, and his own personal numerology of death centering on the number seventeen. Through these and other memories, he develops a soul-searching vocabulary of love for one whose journey continues into the beyond. ‘If you had to make up your own ritual for death, what would it be? Would it be private or shared?’ asked his partner, Marian. Hoffman’s answer is this beautiful document. (San Francisco International Festival Catalogue, 2002)

What these ashes wanted places flesh on the poet Ann Carson’s words “…death lines every moment of ordinary time.” With this work Hoffman resides in an acutely intimate time, a daily practice of loss lived precariously between the terror of psychic disintegration and the provisional solace taken through public rituals of mourning. What these ashes wanted is not a story of surviving death, but rather, of living death through a heightening of the quotidian moments of every day experience. (Images Festival Catalogue, Toronto 2001)

“We are very pleased to present Philip Hoffman in person to present the Vancouver premiere of his latest film What these ashes wanted. Hoffman has long been recognized as Canada’s preeminent diary filmmaker and is keenly attuned to the shape of seeing, foregrounding the image and its creation as well as the manufacture of point-of-view. What these ashes wanted is not a story of surviving death, but rather, of living death through a heightening of everyday experience. The film draws on images and sounds gathered over the course of Hoffman’s relationship with Marian McMahon, from their early meetings in the mid-80s to her unexpected death from cancer and beyond. The three parts of the film (entitled “He always thought they would grow old together”; “Four shadows”; and “17”) form a rich combine of hand-processed film, video diaries, sound recordings from daily life and epistolary voice-over. What these ashes wanted is the result of several years of hard work coming to terms with the traces and fragments of a life that has ended but whose presence persists.” (Alex Mackenzie, Blinding Light Cinema, 2001)

“For a medium that so often relies on images of death for effect, there are few films that truly explore the subject of grief. Perhaps that’s because absence is not easily conveyed in an art form that excels at simulating a direct experience of the present-the haziness of memory is more smoothly rendered in literature. Cinema ofen doesn’t know what to do with emptiness, and the death of a loved one leaves a space-physical, emotional, psychological-that can never really be filled.

Phil Hoffman’s What these ashes wanted, the latest example of the veteran Toronto filmmaker and York prof’s self-described “experimental diarist cinema,” is an honest and very moving attempt to represent that absence and negotiate a way through it. Two lines in the film are particularly relevant. In a phone message left for Hoffman, an unnamed friend passes on a line from Mark Doty, “In times of great grief, it was important to go through the motions of life. Then, eventually, they would become real again.” The second quotation comes from Hoffman’s partner Marian McMahon, a fellow filmmaker and teacher who died of cancer in 1996. “If you had to make up your own ritual for death,” she asks Phil, “what would it be? And would it be shared or private?”

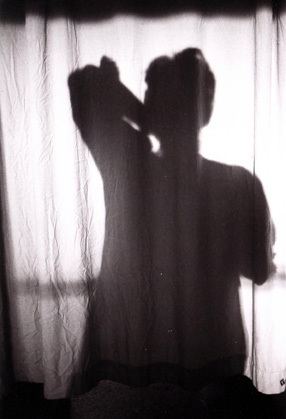

Completed in 2001, What these ashes wanted — which combines hand-processed film, video diaries, found sound, text and narration—is a ritual of grief that seems both shared and private. Our own stories of grief fill the gaps between Hoffman’s images of Egyptian tombs, wintertime frolics and insect activity. Hoffman also includes several awkward attempts to capture his partner on camera. Of course, she never can be captured. He can only take the meager amount of evidence that he has collected and arrange it in a manner-such as the torrential din of overlaid telephone messages in the film’s second quarter-that illustrates the extent to which their lives were integrated. His pain and confusion over her loss is conveyed with a clarity and directness that is rare in experimental film. Like many of Hoffman’s films, what these ashes wanted has the precision of a haiku.

Yet the experience remains private as well. Some of the imagery-the ladybugs, the broken cups, a mysterious photo of Guadalest in Spain—is allusive in meaning, part of the system of signs that is particular to every couple. And throughout the work, there is the sense that preparing What these ashes wanted constituted the “motions of life” that Hoffman performed in order to make his life feel real again. No wonder the film is so powerful.” (Good Grief by Jason Anderson, Eye Magazine, October 9, 2003)

“The image is not enough, though sometimes, it comes close. Toronto experimental filmmaker Philip Hoffman’s most recent film is a rich, densely textured lament for and celebration of his life partner, Marian McMahon, who died suddenly and unexpectedly several years ago. A mosaic of memory, the film weaves together images of McMahon, of their farmhouse before and after, of places visited together and apart. Hoffman’s dark intimations of death and a sonic collage of impassioned messages left on the answering machine. There is also a poignant explanation of Hoffman’s own role from childhood as the family photographer. Throughout this courageous work, Hoffman investigates the oddness of the processes, technological and otherwise, that we invent in order to remember. At the same moment, he also sanctifies them. More than a strictly personal work that excludes the viewer, Hoffman’s film transcends its own intimate power to ponder time itself. Indeed, its diary structure suggests and even demonstrates how the cinema, with images and sounds, can create, destroy and reconstruct temporal experience. What these ashes wanted constitutes a poetics of loss, a valentine to the lived paradox of the very real presence of absence. In the elegiac tradition, it is also an affirmation of the tough, sad, beautiful burden we must undertake to care for those who have departed and those who remain.” (TAKE ONE, May, 2002 by Tom McSorley)

“Philip Hoffman’s What These Ashes Wanted is one of those films that forces you to rethink the medium. There are pictures, yes, and movement, light, and sound. There is, however, no narrative, and yet there is emotion. Both of these last two points are remarkable. To make a film that is genuinely non-narrative is no small accomplish¬ment. At a recent exhibition of short films, I listened as budding visual artist Victoria Prince attempted to explain that there was no narrative link among the images in her latest experimental video, despite an audience member’s insistence that he had been told a story. Last year, soi-disant “guerrilla projec¬tionists” Greg Hanec and Campbell Martin were forced to concede that peo¬ple will find a story in their work pro¬vided they look hard enough: audiences tend to do so. The fact is, there is some¬thing hard-wired in the human psyche that forces us to find continuity where there is none.

What makes What These Ashes Wanted unique and interesting is Hoffman’s ability to override our inherent expectation of being told a story. We learn that his longtime partner, Marion McMahon, has died of cancer, and that the film is an expression of his grief, but that’s only what it’s about. Nothing actually happens in it, just as nothing in the physical universe happens to us while we’re sitting and reflecting on the past. It’s assembled from nostalgic pieces of video footage, Bolex film, still pictures, words, music, poetry and seemingly random micro-montages that fade into obscurity like fragmented memories. “In times of great grief, it was impor¬tant to go through the motions of life,” he narrates, recalling author Henry James. “Eventually, they would become real again.” Hoffman edits these motions together the way that Jackson Pollock paints. He expresses his grief over his lost loved one not through the images themselves, but through the physical act of filming them. The images such as an empty room, an inventory of mementoes, and a field of sunflowers, coupled with a mournful monologue and a montage of unanswered voice-mail messages, carry all the weight of emotional brush strokes. If Pollock was an “action painter,” then Hoffman, I suppose, ought to be called an “action filmmaker;” that label, however, might cause confusion. Instead, call him a documentarian of the human soul.” (A Dream for a Requiem, Winnipeg Free Press, 2003)

AWARDS & SCREENINGS

2002 – Golden Gate Award, New Visions, San Francisco International Film Festival

2002 – Gus Van Sant Award, Ann Arbor Film Festival

2001 – Telefilm Canada Award, Images Film Festival, Toronto

DISTRIBUTION

Canadian Filmmakers’ Distribution Centre

401 Richmond St. W., Suite 119

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V 3A8

416-588-0725 bookings@cfmdc.org

www.cfmdc.org

Canyon Cinema

145 Ninth St. #260

San Francisco, CA, USA. 94103

415-626-2255 films@canyoncinema.com

www.canyoncinema.com

REVIEWS & ARTICLES

Philip Hoffman, diarist filmmaker

by Monica Nolan, Indie Circuit, March/April 2004

Living as Filming

Philip Hoffman interviewed by Barbara Sternberg (2004)

No Epitaph

by Karyn Sandlos, Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom/Sandlos, YYZ/Insomniac Press, 2001.

Phil Hoffman’s Camera Lucida

by Brenda Longfellow

He always thought they would grow old together (text only)

CANTRILLS FILMNOTES

A Dream for a Requiem

Review, by Peter Vesuwalla

Stet

by Michael Cartmell