vulture

Experimental Film and Photochemical Practices by Kim Knowles: “Sections of the film were processed and tinted with a variety of flowers, fruits and plants from around the farm –magnolia, hyacinth, hydrangea, daffodil, rhododendron, pond algae, hosta buds, wild garlic seeds, tansy, aster, echinacea, sunflower and walnut. From this perspective, vulture, is more than just a visual appreciation of the land; it is a complex material engagement with an ecosystem that draws out the expressive possibilities of living things beyond conventional forms of representation. Over a shot of a flying bird, we hear a child relating fragments of information about vultures and their hunting habits. `Vultures live together, and they don’t fight, they help each other’, says the child. `I didn’t know that’ replies Hoffman. Behind this simple exchange lie multiple layers of signification that testify to the intellectual and spiritual depth of the film, and, at the same time, point towards a philosophy of collective nurturing that quietly runs under the surface of the Independent Imaging Retreat (aka Film Farm).”

vulture (16mm, B&W, COLOR, Conventional & Flower/Plant Hand-Processed to Digital, 57 MIN., 2019)

by Philip Hoffman

Direction & Camera: Philip Hoffman

Edit and Sound Mix: Isiah Medina & Philip Hoffman

Sound: Clint Enns, tones/originating music by Luca Santilli and Kennedy

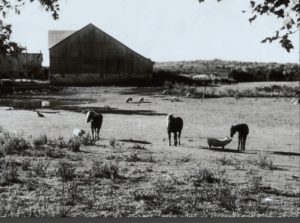

`vulture’ sets its sight on farm animals and their surrounding flora. Static shots and slow moving zooms, follow the grazing animals in their minute inter-species exchanges. When left to roam together the sensibilities of these “beasts” are allowed to surface.

The film was shot and processed with various means including flower/plant processing carried out as blooming occurred, from 2016-18,. In some cases a salt bath was used for fixing the film which was left soaking in the dark for 3 days.

Vultures hover over the barn, from high, with razor sharp eyesight, and a keen sense of smell. Together, they stalk and share their decaying sustenance. Intense acid in their stomach allows them to digest great quantities of their dead prey, without falling ill. -Ph

Awards

Fugas International Award 1st Prize, Documenta Madrid 2020

Environmental Certificate for Eco-Sensitivity, Docpoint Film Festival, Helsinki 2020

Kodak Cinematic Award, Ann Arbor Film Festival 2019

“for its beauty, the perfection of the relationship between sound and image, its radical concept of cinematographic time, the sophistication of the montage, but above all, for its non-negotiable commitment to the essence of cinema – the image in time – and the didactic and community context that it generates around its work”Fugas International Jury, Documenta Madrid: Haden Guest, director of the Harvard Film Archive, Dora García, artist and filmmaker, and Raúl Camargo, director of the Valdivia International Film Festival (Chile)

Screenings

Canyon Salon-San Francisco, Ann Arbor Film Festival-USA, Edinburgh International Film Festival, DocLisboa-Lisbon, Silent Green-Berlin, DocPoint-Helsinki, MDFF CinemaScope Selects TIFF Bell LightBox-Toronto, Documenta-Madrid, Strangloscope Experimental Film Festival-Brasil, Forest City Film Festival, London

Reviews & Articles

Kim Knowles, Edinburgh International Film Festival 2019: Last year we celebrated Canadian experimental film, showcasing works that have emerged from Phil Hoffman’s Film Farm – The Independent Imaging Retreat in Mount Forest, Ontario. This yearly gathering is an important example of the alternative communities that both emerge from and facilitate the continuation of photochemical film practice. This year, Film Farm celebrates its 25th anniversary, and we’re honoured to welcome Phil to Edinburgh with his medium-length vulture. It’s a beautiful and contemplative study of interspecies co-existence, where farm animals roam freely and the camera patiently observes their various interactions. Shot on 16mm film and processed with plants and flowers, it’s also an exercise in eco-sensitivity on so many levels.

Jordan Cronk, Off the Grid (on Hoffman’s vulture) in Cinemascope 2020, MDFF Selects, TIFF Bell Light Box: Nature plays a different but equally ominous role in vulture, an unassuming yet sublime featurette by veteran Canadian filmmaker Philip Hoffman. Assembled by the director over a period of two years, the film comprises 16mm footage shot on Hoffman’s farm in Mount Forest, Ontario that the filmmaker then photochemically processed with natural plant and flower pigments, resulting in a roughhewn, multivalent display of richly tinted and textured celluloid. To hear Hoffman tell it, his analog approach to cinema is part and parcel of a universal cycle of survival and sustainability; like a vulture, his film feasts on the very elements of its production, finding aesthetic nutrients in its every ingredient.

Following a brief shot of Homer Watson’s turn-of-the-20th-century landscape painting The Flood Gate, the film commences with a procession of slow, Wavelength-esque zooms towards a variety of animal life (pigs, horses, cows, goats, chickens) before shifting focus to take in the larger ecosystem surrounding the farm fauna: overhead, birds of prey patiently circle, while in the distance, tractors plow the land and farmers work the fields. The film’s landscape imagery occasionally recalls Nicolas Rey’s autrement, la Molussie (2012) or the work of the late Peter Hutton, though the quietly swelling audio frequencies—the sound is credited to Luca Santilli and Clint Enns, with a mix by experimental filmmaker Isiah Medina (88:88)—portend something far less comforting. Like Wilcox, vulture forgoes direct sound; instead, the distant din of fluttering distortion echoes across the stereo field like helicopter blades on the horizon, with the occasional sample of a young boy’s voice emerging from the void as if summoned from another dimension. Before long, those unassuming establishing shots (which appear mostly untouched by any post-production techniques) give way to a series of colour montages that cut together heavily treated images of plant, animal, and human life from around the farm—an idyllic vision disrupted by the subliminal threat of violence and industrialization. Rather than let the threat loom, Hoffman reworks a selection of this same material for a bracing coda in which the previously placid imagery is subjected to a caustic combination of rapid edits and atonal musical flourishes. (Unsurprisingly, both the sound and edit for this section is credited to Medina.) “Vultures live together, and they don’t fight, they help each other,” the boy says at one point—a perfectly succinct bit of childlike wisdom for a world in which pleasure and peril often go hand in hand.

Andrew Robertson, Edinburgh International Film Festival 2019: Vulture is not an easy film, one shot through with the materiality of film. Though it’s only the credits and the programme notes that will tell you, it helps to know that its celluloid was processed with natural dyes and other substances extracted from a bank of flowers, a process that has embedded itself in scratches and flickers and streaks projected upon the screen. There are experimental films that do not with them bring warnings of strobe nor squalling tones somewhere in the electronic sonic region but this is not one of them. The chemistry of film and filming is such, though, that it makes something special.

In much the same way that even cover versions of Cage’s 4’33” tell us something about the environment of performance, Vulture is contextualised by cinema performance. A sunny day outside is heard rather than felt in the chuckling wind through flowers as those passing by the emergency door contribute. Shots of watering hole beef and pork still ambulatory as animals with the silent shining of the projector give audiences the chance to hear the meat around them sough and whistle, the suckling of a pig at bovine teat as easy a reminder of (un)nature as the three (by my count) who had enough and made their way back to the world.

Vulture hangs, slow zooms to pigs in hollows, an agricultural oasis surrounded by goats and chickens and horses and tractors and rare human forms and shot by shot there is a sense of place – this wall is that wall, that shadow is here, the trailer brings the horses takes the horses, that wall is this wall. Multiple exposures themselves invite an almost aggressive recontextualisation, the cough and creak of chairs and sitters and the clatter and bark of fit and fitters from neighbouring construction. It overwhelms in places, like a black pudding supper, as much batter as bludgeon and heavier in place.

Philip Hoffman’s work is a textbook Black Box entry, light goes into film, picture comes out. There are processes at play and hints thereof – and this is ever one of the delights of festival film.

There is snow and simultaneous scratches on the film and it’s hard not to think of The Eyes Of Orson Welles some stretch of shoe leather from where I am sitting. There are forms of degradation that add depth and gradation like the bubbles and blisters over and under a babbling brook, a sediment of sentiment that might be clouding my judgement. It is perhaps grain or rain upon the sunflowers, but it has hard not to turn one’s face towards it, to create meaning in a meditative geography, to fall under an alchemic charm. The screening I attended will not be the one that you go to, indeed, some who started the journey with me sought other avenues, but I do not doubt a similar transport awaits anyone who is circled by the vulture. As any child (and here one specific) will tell you, the vulture tells you where the meat is. Cracked marrow and all this is a visceral treat, though its experimental palette may be at once too much for some palates. Reviewed on: 19 Jun 2019

https://www.eyeforfilm.co.uk/review/vulture-2019-film-review-by-andrew-robertson

Forest City Film Festival 2021 here

In Conversation: Philip Hoffman & Charlie Egleston here

Mónica Delgado Desist Film (S8) MOSTRA DE CINEMA PERIFÉRICO 2018 (excerpt, in progress test version):

In Hoffman’s Vulture (work in progress) the farm is the space for the recording of different animals, cows, horses, chickens or pigs, in a suggestive harmony and symbiosis, however, this apparent harmonic ecosystem exists due to the absence of man, who isn’t interrupting this tranquility. In this context, the filmmaker, as the vulture of the title, is capturing (via slow zooms and panoramic shots) or waiting for the bursts which reveal this interaction of the animals in pseudo freedom: a cow nursing a pig, roosters and chickens looking for seeds in the woods, or horses riding in slow motion. But Hoffman doesn’t stay in the tale or naturalistic description, but instead confronts this gaze with the “performances” of the animals, with the scarce presence of farmers, and then with the work on crops free from animals to watch over. If this is indeed a non-finished work, the nobleness of a work like Vulture lies in its choosing of a point of view, where the filmmaker’s function is clear, as a watcher of this uncommunicated fauna, but also in the process that is patented in several parts of the film, where he goes from a use of “clean” celluloid to the contaminated (decayed) texture of flower-developed film, which gives the frame a closer touch with the absorption of the environment… In Vulture’s last minutes, Hoffman adds an appendix which has a different rhythm in its editing, executed by filmmaker Isaiah Medina…This ending subverts the initial bet (flow) to finally return with a significant shot (explosion) and a perfect epilogue, of children in a farm separated from goats by a fence.

I’m pretty astonished by this. The new born from the lasting. A work reinvigorating the lineage of observational forms, taking the digestive tract of the titular animal – it’s estranged eye, too – to create something of a dual linguistic assemblage in image interpretation and evaluation. There is something a bit revolutionary, a bit traditional – but it’s, I beleive, rather enlightening. review by Chaim Kindergelt

Francesco Kazzin on `vulture’

Vulture (Canada, 57 ‘, 2019), or Our Father, Who Art (Were) in Heaven: an infinite, asymptotic zoom, an animality that is not internal to a landscape but which creates landscape, primarily with the gaze, then with the specific and intra-specific interaction, and against a nature that explodes, indeed one would say that blossoms, through the manipulation of plants and flowers in the refulgence of their flowering.

A radical operation, that of Philip Hoffman, assisted by Medina, Enns and Santilli in the interweaving and for the music-sound carpet which punctuates a work in which Cinema is no longer machine nor spirit, but materialistic transcendence of a dissipation that is only apparent: if the World exists, it exists for Cinema, meaning it exists in place of Cinema and thanks to Cinema.

Beyond Deleuze, here cinema is no longer what makes us believe in a world. Film is no longer something thanks to which we can still have faith – that, despite everything – a world exists. Even more wildly, world is dissipation. The multifarious that cinema contains not as a unitary and/or unifying transcendental, but as the ultimate, final and definitive truth for which that two (2) is (1).

Inhabitant / environment, subject / object, artifact / natural element, plant / animal, are expressed by the camera, for which they now find themselves reunited, united sun and moon, black and white and colour, mercury and sulfur, the red man and the white woman. If it seems to act in a mechanical way, this is due to the fact that, in the face of reality, cinema is everything and nothing, absolute fullness and emptiness: everything/fullness because it contains everything, has everything, takes up everything and subsists in its frame; nothing / emptiness because of everything that is shot, any element captures and restores the frame, cinema transcends it, not immolating it as a residue of a fallacious individuality but in the perspective of an overcoming of representation as a relationship between subject and object, reality and fiction, expressed and expression.

Cinematographically speaking, that conception of the “tremendous” for which “void is actually a non-void” is valid. The cinematographic language revolution that the Canadian director puts in place is among the most sensational of this new millennium. In fact, if we consider the film as a lexeme, it is no longer the shot that acts as a “seme” but the self-moving fixation that goes beyond the single frame, connecting it and also separating it from the others.

Not quite the superimposition, nor the minimum common denominator which, in this case, the zoom could be, but the spirit that holds and expands together. The frames, as well as the photograms, cannot be resolved cinematically unless they are in relation to a reality to which cinema, shooting and exhibiting, leaves room for — however, only afterwards.

In other words, cinema comes before reality, and reality finds its place in plain opposition to the cinematographic one, thanks to a retraction of the camera. Landscape doesn’t precede the transcendental subject, but a position, a rectitude of the panorama that, suddenly and for a moment, blinks, and in this “sleep of death” – becomes. A whole real-being emerges that Hoffman can then film and return.

In this sense, the zoom results from the opposite of the principal act that made what will therefore be registered to be: from the emanation to the penetration of what is manifest. The zoom doesn’t aim to preserve, but to be a cure for a nyctalopia, that is, in the final and definitive instance, the condition of existence of the real as such.

Like the vulture, both the destiny of what is on earth and its consubstantiation in the skies, cinema does not find meaning in reality nor does it interpret it. The cinematographic “seme”, that indefinitely differentiates and holds – in a unicuum – both the different and the difference, no less than the differential-differentiating process itself, that movement, in short, that vibration entirely internal to the monolithic stability of film as a work of art, is the word-truth which is beyond, because it is entirely internal, to the word-reality as, however, already expressed in the duplicity of the signifier / signified.

Far from signifying or acting as a signifier, Vulture minimizes, it gets to the insignificant root of the word-truth of reality. It gets to the syllable that, alone, means nothing but expresses everything, since that syllable, and all the syllables preceding it or following it, have in them a trace of a word, of which we have lost grasp.

And this is the cinematographic seme: not the relation to reality, but the decomposition of reality into minimal units which, precisely by losing the reference – due to the disappearance of an all-encompassing unification – pierce it (reality), grasping its essence, the hidden fire and the intimate capable of – by dissolving the link between meaning and signifier, subject and object, reality and fiction – transcending what exists only on the reality plane, as dispersed in the opposition, as signifier or signified, subject or object (or the one and the other, but according to two different perspectives, not communicating and never given at the same time). The vulture is the perfect image, it was said. A persecutory destiny but also the impossible ascendence of what is anchored to the ground.

The matter of which reality is made of, is not spiritualized by cinema, and it is not even a question of liberation/emancipation from the realm of matter; rather, matter finds itself spirit: in the smallest unit, really, that is on the plane of the real, insignificant, here is the proper, non-conflictual manifestation of the existing. What in reality is divided, can be found as a whole in Cinema. For this reason cinema is both the wholeness and the emptiness of reality.

Here lies Hoffman’s most important discovery, it is not cinema that is structured like reality but reality that is structured like cinema (and for this reason it gives itself). The cinematographic sky, the ascension of the material through cinema happens, yes, thanks to cinema, but in so far as the very position of the real, no less than its structure, is eminently cinematographic.

Our Father, Who Art (Were) in Heaven… Reality exists to be filmed, Cinema pre-exists it. Reality is not the condition of Cinema except as its obfuscation – and Cinema shines with this obfuscation. What most binds us to reality, to earth, to fields and animals, to nature and the farm, is also what brings us back to the cinematic essence of reality. Here lies the emphasis of Vulture, materialist theocrasis.

By Francesco Cassin