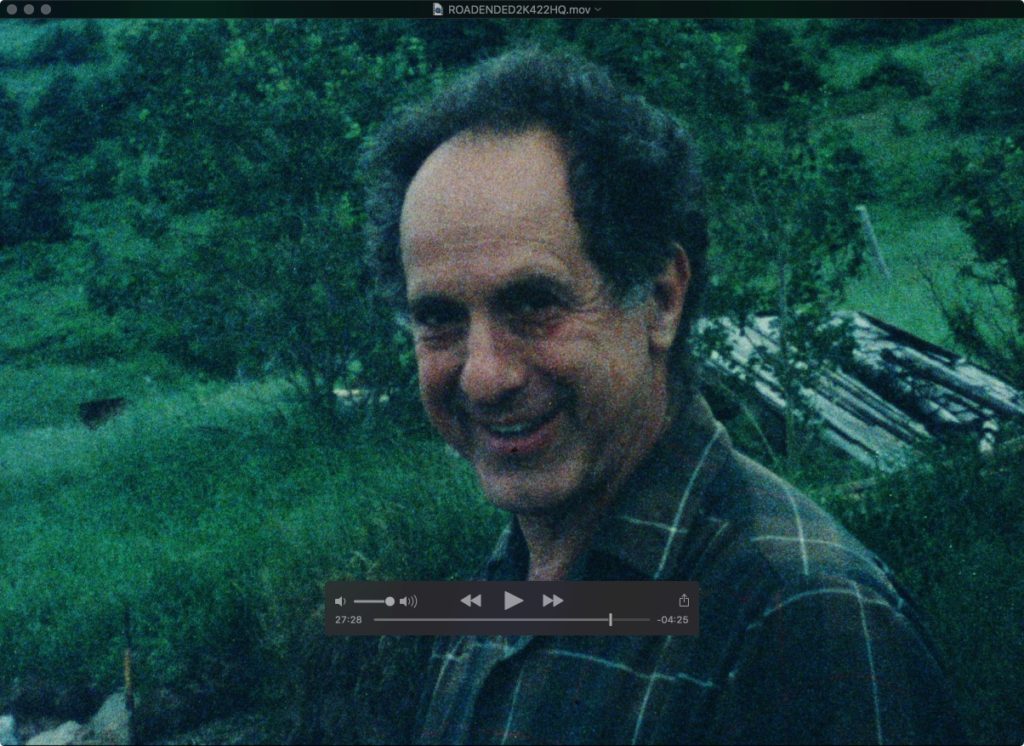

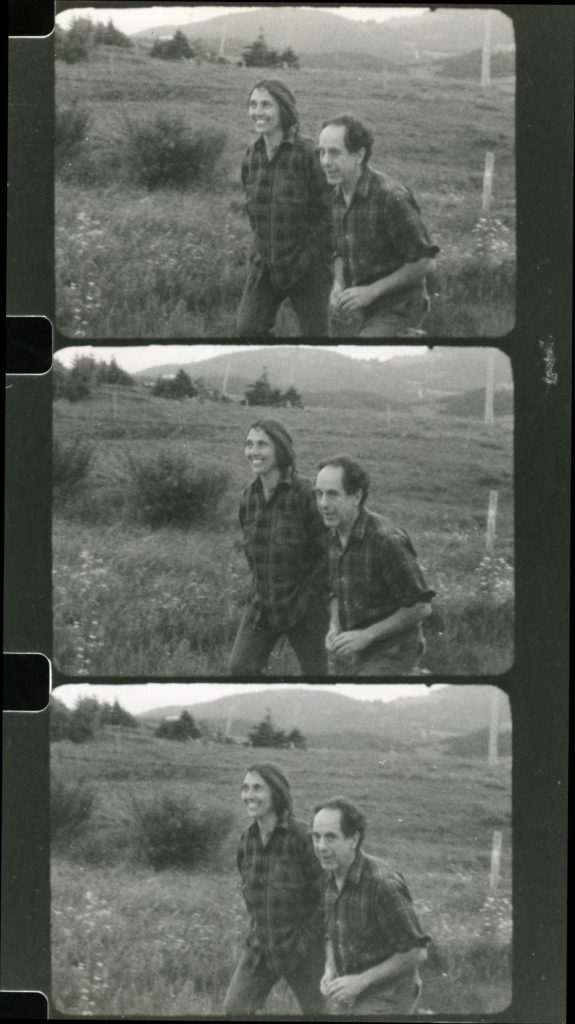

May 1980 Mabou, Nova Scotia. Photo excerpts from Hoffman’s film THE ROAD ENDED AT THE BEACH (1983)

INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT:

JM: Jim McMurray

RK: Richard Kerr

PH: Phil Hoffman

RF: Robert Frank JL: June Leaf

Jim McMurray: How did you happen to find a spot like this?

Robert Frank: Oh, it’s just an accident.

JM: You were just up here?

RF: Well it was on a bulletin board in Port Hood. Yeah, it’s pretty nice.

Richard Kerr: What are the winters like? Pretty severe.

RF: The wind is sometimes pretty rough but it’s not too bad. I like it in the winter.

JM: Where’s the coal mines from here?

RF: Past this house here. See that house? There’s a hole going down, that’s where it used to be. It fell down the tower.

RK: Are they going to use it again do you think?

RF: No, it’s all under the water so it’s too expensive.

JM: Too dangerous too, eh?

RF: …it’s too expensive to come in here and you know look after the track here. It takes a long way to get it out from here.

JM: Can anybody come around here dig themselves and use it in their fireplaces?

RF: People use to do it, use horses, get some chunks. Not anymore.

JM: I sometimes work with, you know like iron. Bending it in a furnace. I went down to the railway tracks and they were selling coal at places where an old railway car had tipped over. All free now.

RF: Where do you come from?

JM: Ann Arbour. I saw a picture in your book. I think The Americans, of someone laying in a park.

RF: Ann Arbour. Yeah that’s with all the cars. There’s a little lake outside Ann Arbour. Not far from…

JM: Do you get away from here very much anymore or do you stick around home?

RF: Well, when I have got to go, I got to go. When you got to go, you got to go. I like it here.

RK: I just saw they had a display of your pictures at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto in the spring. Were you up there at all?

RF: No. No I didn’t go.

RK: Just send the pictures and let them do the talking.

RF: Yeah.

RK: I guess what you know were looking for and I guess it’s in the form of some sort of advice, is that, I imagine there’s no secret to it, but what frame of mind were you in when you did The Americans. And how conscious was it? The spontaneity, this sort of thing.

RF: Ah.

RK: Because you read so much stuff and a lot of it frankly is you know?

RF: I think spontaneity might be a way of not thinking you know. Maybe if I would define it. Spontaneity, I don’t think I thought a lot about it. It was more feeling than thinking.

RK: You just did it.

RK: Yeah.

RK: What sort of line as far as equipment goes, were you outfitted with. The finest equipment of the time or were your tools just what you had?

RF: No, I had ordinary equipment. A couple of Leicas, one with a normal lens the other with a wide angle. It helps with good equipment but I think it’s more important to have good equipment when you do carpentry. It’s more exact. When you’re out there working alone I think that. Then thinking about carpentry it’s not that you’re working together with someone. But doing The Americans at the time, I think that it was wonderful to travel alone.

RK: That’s what we were talking about this morning. This is Phil’s project. I’m doing sound. Jim’s doing the driving and music. We were wondering, to do what he’s doing, to do it by himself, he’d be more mobile. He wouldn’t have to listen to our bitching and complaining you know.

RF: Well if it finally gels, what you do with the tape and what he does with picture. It’s an ongoing process.

RK: Have you ever tried much team work as far as film.

RF: Well with films I think you have to. It’s too hard to make films alone.

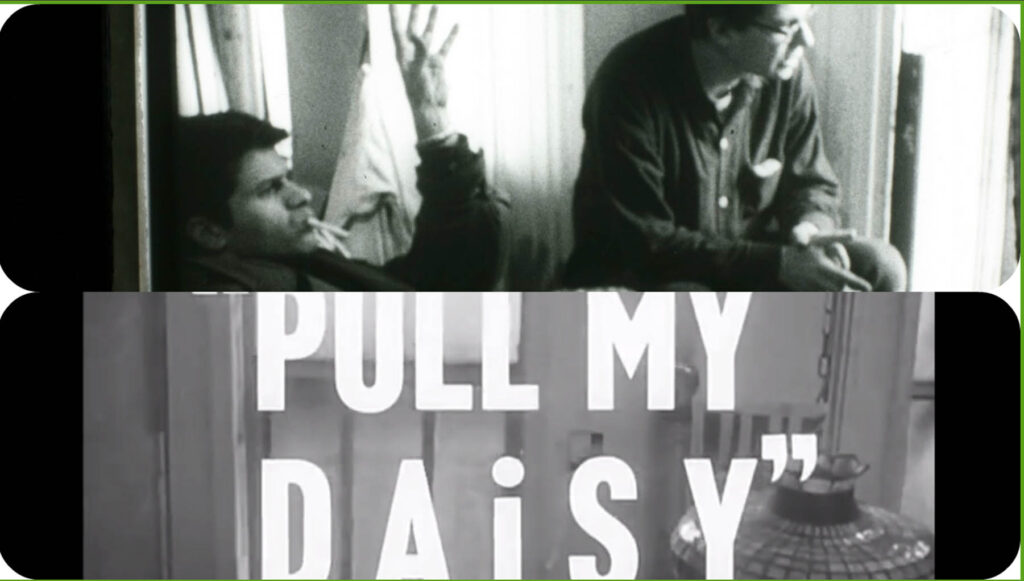

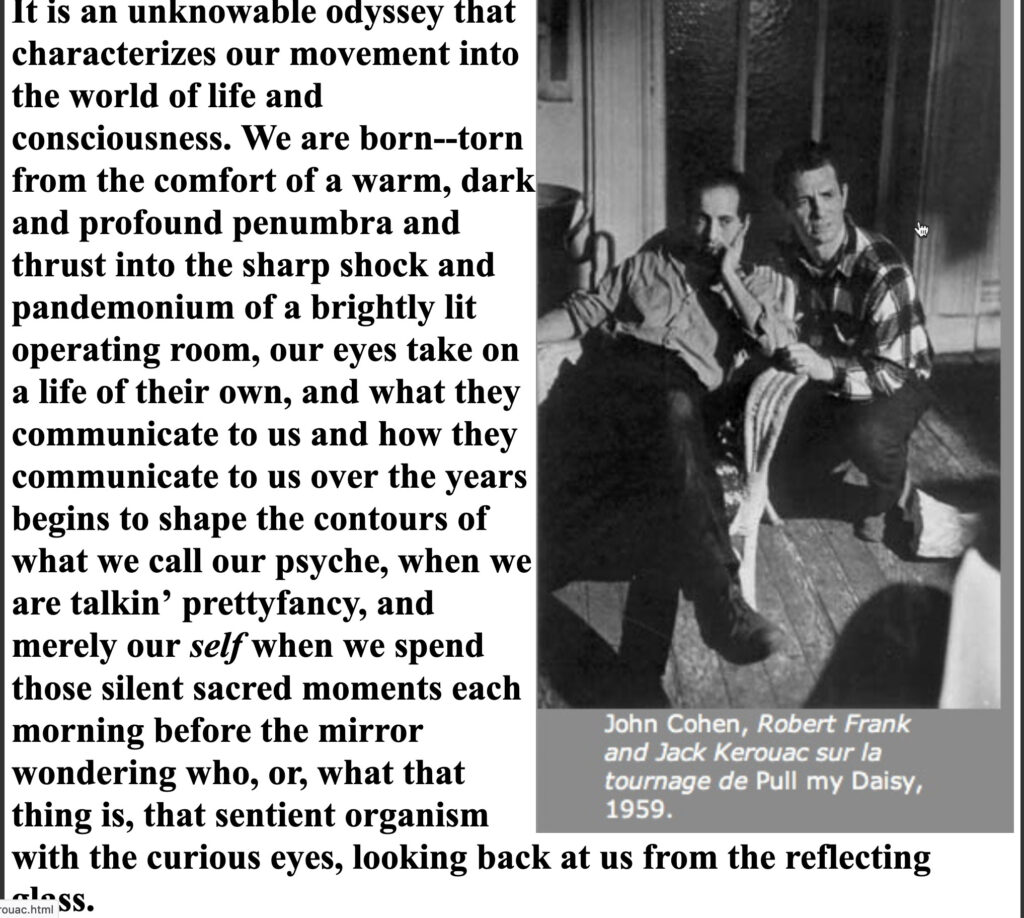

PH: How about Jack Kerouac and Pull My Daisy. Did you shoot the film and then Kerouac did the narration after?

RF: Right. He looked at the film and narrated as he looked at it.

PH: Was that a good way to work?

RF: That could be called spontaneity. I mean that certainly was a spontaneous piece of literature.

screen `Pull My Daisy’

PH: Was there editing involved? I mean did you go to a third person again? After you had shot it and he had done the narration, anyone cut things out? Like, Kerouac’s On The Road apparently has been butchered quite a bit for the publisher.

RF: There was very little taken out. We just had to fit it sometimes, it ran a little bit over or we wanted to put some music in, so some words were cut out, some sentences. But it didn’t happen very often. Of the thirty minutes that he narrated maybe two or three minutes were cut out and that’s about it.

RK: Earlier we were down talking to Allen Ginsberg in th elower east side, NYC, doing some research at Columbia, that he kept there, and I was wondering, is there… those people they seemed like such a close knit group at the time. Are they scattered now or do you have any contact with any of those people? Is it just a time and a place and now you’re in a different time and place.

RF: Well Kerouac is dead… he’s away. Sometimes I see Allen. I never kept that close in contact with them. So, I don’t know. Corso’s living mostly in Italy. I think it pretty much goes apart after… years.

RK: Yeah, that’s what I find with my friends. We just drift I’m out here now and they’re all out in Calgary in the real estate boom. At the time, were the conditions right to work? Were things as free as it looked. You know we were only two and three years old then but we had the image that it was free, that everything just went along… Did it have that feeling to it or is that something the media played upon. Grabbed.

RF: I don’t think that it gets freer. You know good people work. They work the same in 1980 as you would have worked in 1960. Maybe it was freer because you knew less and you were more innocent. Now I wouldn’t be that free simply because I know more about it. Much more.

RK: Are you familiar with the term zeitgeist?

RF: What?

RK: : Zeitgeist. It’s a German word for spirit of the times.

RF: Zeitgeist, zeitgeist. Yeah.

RK: I heard that word when I was in Switzerland about six years ago. That was the word all the people were using. I didn’t know what the hell it meant.

Frank: Well I’ll give you another one. How about Weltschmertz?

RK: Weltschmertz? ha ha…We come from a German town so we get all this. A town in Ontario, Kitchener. It’s a rural German community, so you get osmosis over the years.

RF: I think this dog makes a good soundtrack.

RK: Yeah. I just did a film called Dogs Have Tales, about my other dog. I don’t go anywhere without a dog.

RF: So who is in charge of editing the film?

PH: I am. It’s a project where we all work together. I think one of the things that’s happening in a way, is it’s just gone a week and things are kind of gelling… We all kind of got our separate jobs now, you know.

RK: A guy gave him a free truck. He went to California and couldn’t take it with him. It was fifteen years old ..I did him a favour once and he said take care of this for me it’s yours.

RF: It’s nice.

JM: It is nice.

RF: What kind of truck is it?

JM: It’s a Dodge. An old Dodge.

RF: Wonderful looking. Nice.

JM: Well we put new doors on it, but it was painted… covered with flowers and beautiful things like that. But nowadays I guess you can get away with things like that. Is there anything we can help you with, any heavy lifting?

RF: No I can’t think. No, I don’t think there’s anything.

RF: How long have you been here, five, six years sort of a thing?

RF: No we’ve been here ten years. Eleven years. We came here in 1969.

JM: Wow.

RF: We built this you know? Yeah, it’s satisfying to build something.

RK: You bet it is. That’s something I was never brought up to do but it’s something I want to do.

RF: It’s satisfying to look here, you know? See the water?

RF: Well I mean I thought it would be more like having to look into the camera…like a TV interview, you know.

RK: No. We left the make-up girl at home. Make-up person.

RF: I always liked it when films you know had freedom… when you could move sound and image around. When I was teaching in sometimes Super 8, I always liked that about Super 8 because I completely divorced the image from the sound, and there’s so many possibilities then.

PH: It’s exciting… there’s always something being born,

RF: You always stumble on something that makes sense that enhances the picture itself.

PH: I think of a saying… let the feeling find its own form.I have to remember it for this film. That’s what I’m trying to do … sometimes it’s really hard… travelling is hard enough… It’s two jobs in a way.

RF: I use to think… how is the wind doing?

RK: It’s kicking the hell out of this mic, but what can you do?

RF: Sometimes the wind sounds so beautiful. What kind of a machine is that?

RK: It’s a Sony. A Sony cassette deck. It’s got little toys on it you know …too many gadgets.

RF: You always work with one mic?

RK: This can work with two.

RF: Yeah, but you do everything with one?

RK: As much as possible. I’m not a technical person so I got to find a simple machine. Don’t need a Nagra.

PH: We’re just using this Bolex with 3 or 4 different lenses.

RF: Is that a combination lens? I mean that’s just one lens.

PH: It’s just one, yes. That’s one thing I wouldn’t mind for this trip is maybe not changing lenses so much.

RF: You just work with that one lens?

PH: one or two..wide and normal.

RF: You have other ones but then you have to take it off.

PH: Yeah, It’s the only one I could get a hold of for the trip, but it works well.

RF: What do you shoot? Colour?

PH: Yeah, negative. We’ve shot for three or four years now west and east trips. This is our second time out east. I shot super-8 and collected sound when I first started a while, and now what I’m going to do with the super-8 is blow it up to 16mm and use it sort of as a concrete form of memory. And so over the years we have been returning to places and people …. So hopefully the film will have some history to it.

RF: How long is it since you’ve done the super-8?

PH: 1976… about four years ago.

JM: We came out here last year and got some footage, but the car kept breaking down. It was a newer one then this. Do you still go down to the School of Design in Halifax.

RF: No I haven’t been there since at least three or four or five years.

RK: I was thinking about going there back to school for the fourth time. Think it’s an alright place?

RF: School? Well if you feel like you need to learn something and that’s the way you feel you can learn it. What would you take there.

RK: Art education or something like that. How about teaching I do some teaching now, but you don’t get paid well when you know the stuff but don’t have the letters behind you. They don’t pay you as well. But I don’t know, change my mind every day, that’s what I got one for I guess.

RF: Well if you can go to school that’s nice. It gives you place, not in the streets.

JM: Especially out here as opposed to Toronto. I just got out, been going for years. Got a Masters Degree in Fine Arts and I finally realized that it’s not doing me much good at all. I wish I had worked all that time. ….The dog likes it here. He likes those cliffs, feels like he’s climbing mountains.

RF: It’s your dog, eh?

JM: It’s Richard’s dog.

RF: Oh, yeah.

JM: It was his birthday two days ago, two years old. You getting pretty stuck to this place here? I mean hard to leave?

RF: Well I’m attached we put a lot of money into it. We’ve worked on this for a very long time.

JM: Nice to make something and have something there.

RF: It seems permanent. It doesn’t change. It’s nice to watch nature. Watch the water, the wind, the sea.

JM: That’s what I like. I didn’t really want to come on this trip. It was hard to break myself away. How are the people down here? Pretty nice?

RF: Very friendly, yeah. Well they’re very discreet. There’s a lot of room, nobody bugs you.

JM: This has got a lot of Scottish history … The highlanders or…

RF: Yeah, they’re mostly Scottish.

JM: A lot of ***………*** (?)

RF: Some of them speak Gaelic.

JM: Yeah? Wow.

RF: It’s a good place to live. I don’t know about working. I have a hard time working here but June works a lot. She works on the building. Why don’t we stop for a while?

JM: How do you heat in the winter? Is it wood?

RF: Wood stove, coal.

JM: You just go down in your car or truck and pick it up?

RF: Yeah. When we just came here in 1969 coal was something like eleven, twelve dollars.

JM: A hundred weight?

RF: A ton. And now it’s forty and I guess that’s still cheap.

JM: Yeah. It’s a lot more down in the city..

June Leaf: It’s good huh?

RF: Can they have some tea?

JL: OK. You want some tea?

RK: Then we’ll let you get back to work.

RF: It’s a good day for working today.

RK: Yeah. Not too hot.

JL: Are you guys having tea?

JM: Phil you want some tea? (Phil filming on rocks). A lot of people paint their shingles. But I guess that once you’ve painted it once you’ve got to paint it over and over again.

JL: Most people paint them. They do, they like to paint them. It makes the house look fresh every couple of years.

RF: With just oil.. you know, seems to keep them pretty well.

JM: That’s a pretty colour that, silver.

JL: See these are old shingles, see we’re reusing them they’re very strong. I mean, they’re just like new shingles. Look at that. That was already cracked when we took it off. See we took it off with a shingle puller. That way where you see we’re putting it back it varies.

(The all go in the house for some tea).