(an excerpt from a larger article publication forthcoming)

by Janine Marchessault

I was still a young boy when I saw my first film. The impression it made upon me must have been intoxicating, for I there and then determined to commit my experience to writing…. I immediately put on a shred of paper, Film as the Discoverer of the Marvels of Everyday Life, the title read. And I remember, as if it were today the marvels themselves. What thrilled me so deeply was an ordinary suburban street, filled with lights and shadows, which transfigured it. Several trees stood about, and there was in the foreground a puddle reflecting invisible house façades and a piece of the sky. Then a breeze moved the shadows, and the façades with sky below began to waver. The trembling upper world in the dirty puddle—this image has never left me.

— Siegfried Kracauer (Ii, 1960)

We can see the development of strategies based on coincidence, accidents, indeterminacy, endlessness, and contingency in documentary and experimental filmmaking of the post war period expressly in this light. As a means to work through some of Kracauer’s insights around cinema and the “whole world”, let me turn to a specific work—the short ‘travel’ film Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) by Canadian filmmaker Philip Hoffman. The film was shot under the influence of Jack Kerouac and inspired by the Beat Generation. Kerouac went on the road in the fifties to wander and to have experiences, to create a scene across cities, New York, San Francisco and Mexico. ‘On the road’ refers specifically to a mode of writing that is quite literally writing while en route. It is after The Town and the City and through On the Road that Kerouac developed his art of ‘spontaneous prose’, an improvisational method of writing in time connected to the flow of life like jazz. Famously he used a full roll of Teletype paper that matched the road and typed the novel almost continuously over three weeks. The roll enabled him to write without stopping, without interrupting the flow of words, essentially mirroring the experience of driving. Kerouac like Gertrude Stein before him, associates writing with a phenomenology of the mind, a writing that is “composed on the tongue rather than paper” (Ginsberg 74). Kerouac’s writing does not seek to transcend mediation so much as it does to document its actions so that writing becomes a record of the connection between inner and outer structures of perception, binding bodies to places through time. As much as it pushes the boundaries of presentness, writing like film, is always in the past. Although the fact of mediation between word and image is altogether different as Kracauer would stress.

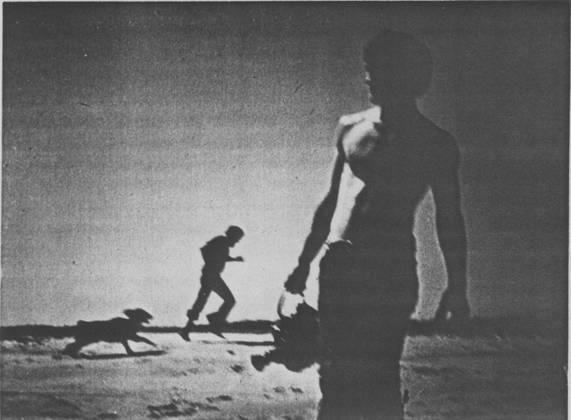

Hoffman made Somewhere Between, after attending a conference devoted to the legacy of On the Road in Boulder, Colorado. Yet Hoffman’s film is not so much on the road (the highway) as it is on the street, featuring two cities (Boulder and Toronto) and towns somewhere between the cities of Guadalajara and León. The film cuts across various scenes in these places with lengthy (often twenty-eight seconds) unedited sequences of action and black leader as “measured pauses” (Kerouac’s silence or breath) between sequences. These juxtaposed moments play out a reflexive rhythm that foreground the randomness and stubborn indeterminacy of the images of everyday life, and of their placement in the film. We are presented with situations that are delimited without being explicated. The film opens with a text on the screen: “Looking through the lens/ at passing events/I recall what once was /and consider what might be.” Two early sequences in the film give image to these words. The first is an image of what is now a cliché of globalization. The static camera poised on a street corner in the centre of a small town in Mexico, frames in long shot, a mule and buggy parked beneath a large red Coca-Cola sign, a tangle of telephone wires above low rise dilapidated buildings. The only movement in the frame is the cars, driving in and out of it, and a woman and child crossing the street. Yet movement and layers of interaction are implicit in the juxtaposition of the mule and the global corporation, which co-exist in this place. This image is preceded by another static shot of a church down the street, doubly framed between two pillars of a Catholic arch. Looking in, the camera reveals someone deep in prayer. After a motionless few seconds, a child interrupts the stillness of the sequence, enters the frame and begins a game of crawling up and down on chairs. The child’s sudden appearance is precisely that kind of “unexpected incident” that Kracauer delights in—“the stirring” of nature and people that the Lumiére films first captured. The kind of “spontaneous writing” that we often find in experimental ethnographies favors a self-reflexive methodology[1]. In this instance, focusing on the physicality of the scene to include the temporal structure imposed by the camera (i.e., the spring wound Bolex’s 28 second take) and the filmmaker. The acts of “looking through the lens” as Hoffman’s text tells us, calls upon a time-based aesthetic where past and future co-exist beyond the edges of the frame. Yet it is not only the film strip/ flow of life analogy that foregrounds this temporality. It is also the reoccurring themes of religion and children, of tradition and horizons that Hoffman finds across the different places in the film. Given that the film concerns the story of a Mexican boy run over by a truck somewhere in Mexico, these themes resonate throughout. The boy’s death is an event that the filmmaker refuses to film (or include in the film) but instead conveys through a poetic text on the screen that is intercut throughout the film. Filled with black holes overwritten with the poem that remembers the boy’s death, the film’s architectonics are structured by the words that never conflate the commonalities between the situations. The poem embeds the boy’s death in all of the images of the film so that it is not inconsequential to the corporate sign, the superstructure in the opening images but rather stands in a contiguous relationship to it as to all the images in the film. The melancholic saxophone that draws the line from Mexico to Colorado to Toronto, seems to synchronize momentarily with the musicians and children holding out cups to collect money in these different places but then separates and floats over them from an off screen space that leaves the frame open to a multiplicity of found stories: children playing games on different streets in different cities, a crowd kneeling outside a church, the Feast of Fatima procession in a Portuguese neighborhood in Toronto, little girls dressed as angels and streets lined with telephone poles, the beautiful patina of pealing walls aged by the weather, graffiti palimpsests in different languages, a paint brush sketching a likeness of Jesus from a painting of Jesus, a child crawling up and down on a large sculpture of a sea shell in an outdoor street mall, a pond surrounded by trees at dusk. The camera stages situations from a distance and in long shot; sometimes the movements of bodies are slowed. But it is the materiality of the built environment that is framed to equalize the human and the non-human (trees, benches, windows, sidewalks, statues, cars, signs) which are counter influencing and interpenetrating processes. We see here the manifestations global cultures, national and urban idioms and technologies that the film stages as commonplace.

In the study of localities, filmmaker and anthropologist David MacDougal points out that it is not singularities but interconnectivities and flows between particular cultures that lead to the cinema’s capacity for deeply phenomenological and pedagogical gestures. Somewhere Between gives us the interval or the interface between places where identities and experiences take up their meanings in Hoffman’s memories of a shared world. Yet it is also the characteristic of the “found story” that it remains open, fragmented, that it burn through myths and clichés. It must resist the “self-contained whole” that would betray its force by casting a tight structure with a beginning, middle and end around its anonymous core. The found story Kracauer explains arises out of and dissolves into the material environment, often in “embryonic” forms that reveal patterns of collectivity (Theory 246). The found story comes from the aesthetic of the street and we should add, holds infinite possibilities for the psychic investment in the whole even as it takes it apart. In the end, Hoffman may well have broken with Kracauer’s prescriptive visual aesthetics by staging reality with word, image and black leader in a way that actively petitions the dreamer to envision what was and what might be. What holds the spectator’s interest in Hoffman’s film is the gap, the place of imagining: the black smoke from the truck, the children weeping, the sky and the boy’s spirit as it “left through its blue”.

[1] Take for example the films of Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Jean Rouch, Agnes Varda or Chris Marker who use the camera as an intrinsic aspect of performance. We could also include some of the more self-reflexive documentaries by the Unit B directors at the NFB of Canada. Cf. Catherine Russell Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video (1999).

Read whole article here