by Karyn Sandlos

from Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom/Sandlos, YYZ/Insomniac Press, 2001

When Ann Carson writes “…death lines every moment of ordinary time” (166) she suggests that mortality resides in the quotidian details of our lives. Time, as we know it, is a progression that is measured by clocks, calendars, the passing of days, the changing of seasons. When a loved one dies, the knowledge of time passing may allow us to hover over the chaotic reckonings of the present and imagine an afterwards; a prospective view that makes the immediate impact of loss bearable. But in the midst of bereavement, ordinary time is a view from the proximate clutter of a present that can’t envision a future, a heightening of the minor drama of death that permeates the everyday. For Carson, the kind of death that “lines every moment” doesn’t quite amount to an event, to the actual fact of Death. The problem is that rather than surviving death, we live it.

What took place every day was not what happened every day. Sometimes what didn’t take place was the most important thing that happened.

— Marguerite Duras, Practicalities.

Death is a recurring fascination in Phil Hoffman’s oeuvre, a body of films that seem to rehearse a penultimate death that will take Hoffman to the outer and inner reaches of grief. In the film cycle that concludes with Kitchener-Berlin in 1990, be it the figure of a young boy lying dead on a Mexican roadside or an elephant falling at the Rotterdam Zoo, death is an indelible presence that is often left out of the frame. After 1990, by undertaking a series of collaborative works (Technilogic Ordering 1994, Sweep 1995, Destroying Angel 1998, Kokoro is for Heart 1999) and inviting audiences to order the progression of his Opening Series films (1992 ongoing project), death becomes a method in which Hoffman as maker is displaced. Phil’s latest work, What these ashes wanted, documents the death of his late partner Marian McMahon from cancer, and the film is a declaration of insurmountable grief. But the death that Hoffman has been rehearsing since assuming the role of familial custodian of memory at the age of fourteen is his own.

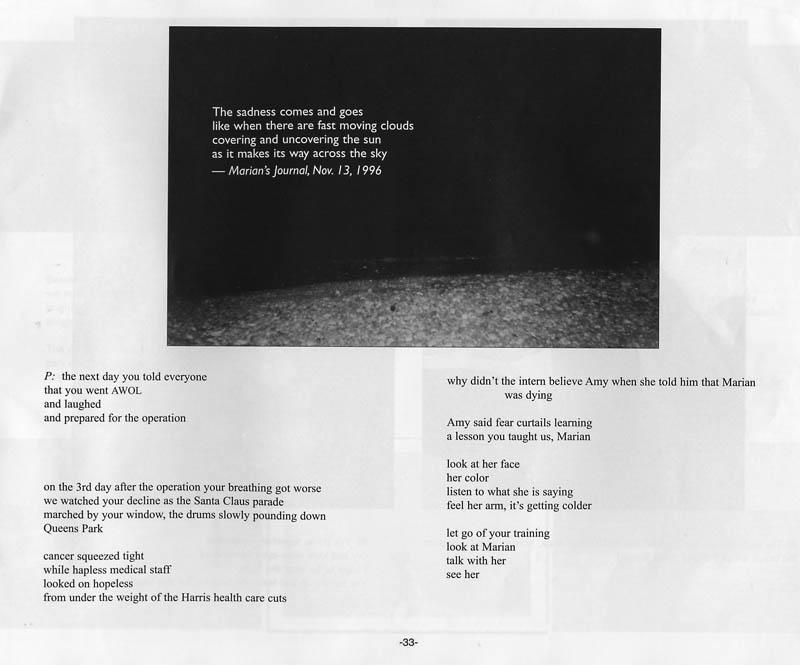

What these ashes wanted is populated by the familiar – even banal – images of home and family that I have come to expect from Hoffman, but here he makes use of the ordinary to evoke a profound experience of loss. Hoffman’s iconography is that of the immediate material that surrounds him: a garden alive in summer and dead in winter, the view from a hotel window, highway traffic signs, the brick wall of the farmhouse where he lives. Ashes finds a gentle rhythm in the unexceptional that acts as a refrain throughout the film, proposing a way of seeing how extraordinary loss illumines the daily practice of death-in-life. The film is not a story of surviving death, but rather, of living death, of making life hospitable to the prospect of mortality. It is through Hoffman’s carefully crafted attention to the minor details of loss that the presence of death in the ordinary fabric of life is acutely felt.

If you can read this you are standing too close.

— Epitaph for Dorothy Parker.

Bereavement has become a thriving industry in Western culture, replete with therapeutic approaches and self-help strategies that instruct on how to grieve well and for discreet periods of time. Many forms of bereavement counseling treat life after loss as a healing strategy, a way to reach toward a time when grief will be less shattering, when the pain of loss will be less present. Funerals also act as occasions for shaping and articulating grief, and for marking the distinction between the mourner and the mourned; a kind of reality check that affirms what the mind at once understands and resists knowing. And it may well be the case that loss is far too amorphous and terrifying without the containers of formality into which we are compelled to pour it. Hoffman’s project is, however, less committed to protocol and more concerned with a practice of bereavement that mixes psychic disintegration with the provisional solace taken through secular therapies or devout rituals of mourning. Early in ashes we partake of a playfully private moment shared between Phil and his late partner Marion McMahon, the first of several sequences that will draw us into the small circle of their relationship throughout the film. Heavily bundled against the cold they frolic, home movie style, in the yard outside their Mt. Forest home. The camera moves erratically across the brick wall of the farmhouse at close range; an uncomfortable proximity is felt in observance of an intimate game from which the burdens of the world seem to fall away. Phil touches the wire fence, feigns electric shock, and laughs. Filming this moment, the couple play at death while reaching for posterity – for permanence – bringing the underlying tension that haunts ashes to the surface.

People may die and be remembered, but they only disappear when they are completely forgotten, when no one ever uses their name.

— Adam Phillips, Darwin’s Worms.

It was Freud’s observation that dreams are populated by incidental images and fragments of experience from conscious life. The death of a loved one, he noted, is often obliterated from the dreamscape only to return to memory with unusual force upon waking. (78) Perhaps, then, in the midst of grief the unconscious makes itself known through a heightening of the minutae of waking life, like a long, slow swim under deep water where every movement, every sound, and every glimpse of color and light is attenuated. The irreconcilable clash between psychic longing for the lost loved one and the reality of absence is less an event than a palpable emptiness, a heightened view from the jumble of experience that has fallen out of step with the continuity of time. In ashes, the brick wall of the farmhouse contrasts the brick facade and pillars of a more monumental structure, a relic of ancient history. A figure walks slowly past an Egyptian temple, appearing, disappearing and reappearing from behind the columns. When the body is absent, this sequence implies, the shadow remains.

A person will walk through a hundred doors to carry out the whims of the dead, not realizing that he is burying himself away from the others.

— Michael Ondaatje, Anil’s Ghost.

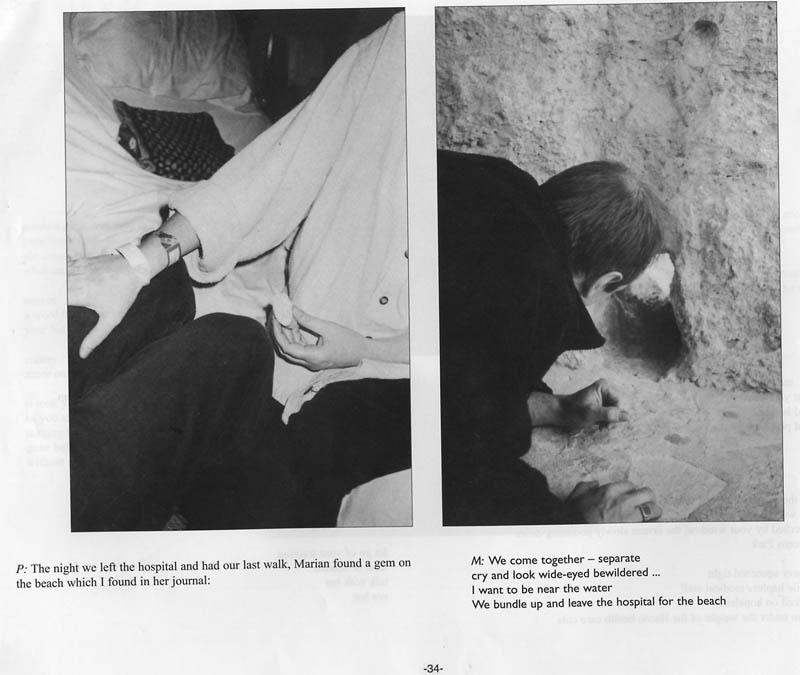

In the days approaching her death Marian asks, “If you had to make up your own ritual for death what would it be? And would it be private, or shared?” Phil responds that it should be shared, and his tone resonates with the force of this deeply held conviction; for Phil, death is a lived practice that must necessarily be shared if one is to live at all. It is often said that funerals are for the living; but how, precisely, does ritual help us grieve and move on? With this question in mind, I often visit cemeteries and wander amidst gravestones belonging to people I have never met. Something troubles about the tone of epitaphs. The words say that the loved one is gone. Etchings in stone mark the finality of death, but they don’t account for how life is lived as the practice of death. The severing of attachment and the abruptness of absence may be life’s most shattering experience, yet loss itself has a lingering presence in life. Lovers leave, but the inevitability of death, if not desirable, is wholly enduring.

Death, although utterly unlike life, shares a skin with it.

— Ann Carson, Men In the Off Hours.

Ashes is no epitaph, no tribute to the solace of monuments or the passing of time. In his latest work, Hoffman remains in his own time, a daily practice of loss lived precariously on the margin between disintegration and ritual. A voice on Phil’s answering machine enjoins that “in times of great grief it is important to go through the motions of life until eventually they become real again.” When Phil films Marian making calls on her route as a home care nurse, he rides in the back seat and watches her face in the rear-view mirror. Caught up in the demands of the everyday and the immediacy of the task at hand, Marian thinks out loud about how peculiar it feels to provide intimate physical care to complete strangers. In illness, she observes, the body becomes public property. The conversation takes on a heightened anxiety as Marian describes the awkwardness of the situation, and her inability to talk with Phil about things she really wants to talk about while he complains about the weight of the camera. The nuances of Phil’s response are missed in an exchange in which Marian teases him for failing to appreciate the gravity of her insights. The conversation becomes a speculation on the daily minutae of loss; the disappointments, missed connections, and absences that act as small rehearsals for the larger drama of death.

Although I never met Marion McMahon, I remember her in a very particular way. I was a new graduate student waiting for a meeting in the hallway outside a professor’s office. Wanting to absorb the culture of collegiality and ideas I studied my surroundings. The walls were plastered with memoranda; posters advertising political rallies, calls for papers, and cartoon strips ¾ the clutter of academic life. What I recall most vividly is a poem that was taped to the door directly in front of me. Reading that poem, I felt a momentary break in time that I have yet to understand.

Perhaps there are no accidents. I had skimmed the eulogies on e-mail, and heard fragments of conversations in the hallways about a colleague who had passed away. She was a doctoral candidate, and she died of cancer just as her dissertation was approaching completion. The poem was written by one of Marian’s professors, but it read as if her hand was urgently tracing his words…I am still here.

She might have spoken the words, or whispered them.

It is a common clinical experience that bereaved people fear that talking about the person they have lost will dispel their contact with them.

— Adam Phillips, On Flirtation

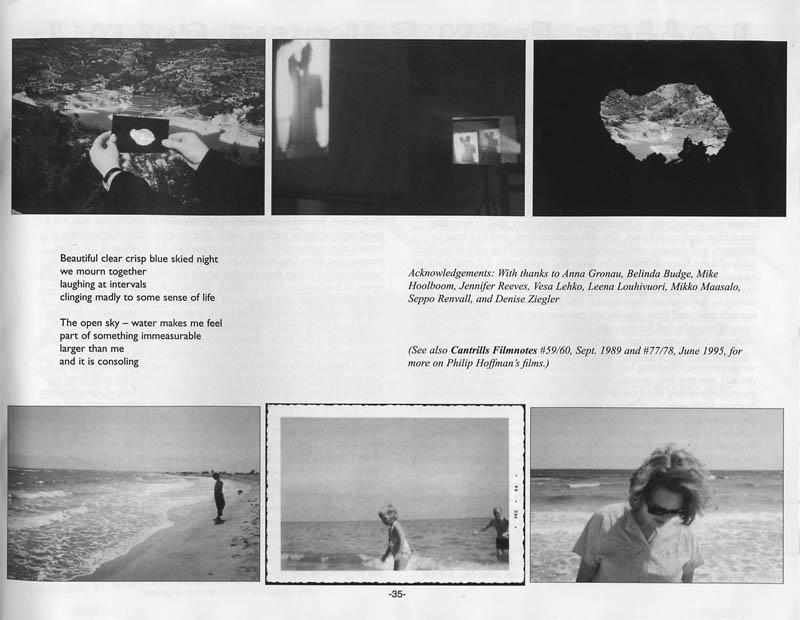

Ashes speaks most profoundly through a story that Hoffman struggles to put to words, not only because he cannot bear to articulate his loss directly, but because language itself can only approximate the void that is absence. In ashes, loss is evoked through a reordering of referentiality, a fragmentation of the details Hoffman depends upon to order his world. A window provides the only source of light for a darkened bedroom. Although the light fluctuates, it is impossible to determine when it is morning and when it is evening. The camera hovers on time lapse. Are seasons passing, or merely hours? Formless images, shapes, and shadows are intercut with lush scenes of the garden awash with the color of emotion, with the vividness of an image one might wish to have shared with a lover. Anecdotal remnants of Marian contained in answering machine messages procure the flavor of shared lives, recount daily events, confirm appointments, and announce the birth of a baby girl.

A nurse calls, wondering what to do with a blouse left behind at the hospital.

It is possible that we have no idea what secular grief is; what grief unsanctioned by an apparently coherent symbolic system would feel like

— Adam Phillips, PromisesPromises.

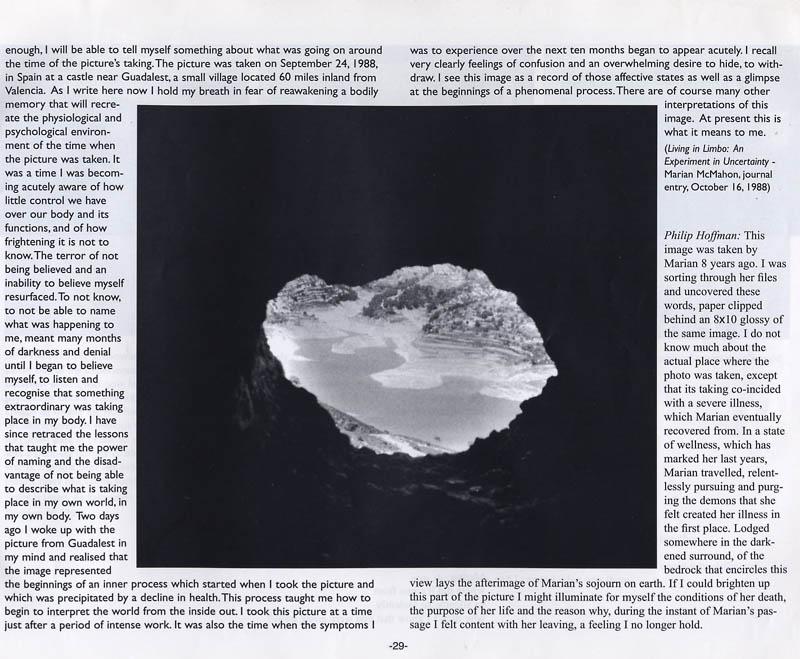

Obsessing over the hidden meaning of a photograph taken from inside a cave, Marian reflects on learning to live life “from the inside out,” from the midst of happenings yet to be understood, yet to be integrated into a coherent realm of experience. Transposed in text across the darkness of the cave’s interior, her reflections on loss – in this case the loss of memory – resonate with Phil’s own struggle to articulate his grief. The power of naming, Marian insists, gives experience its credibility. Attuned to the capacity of the symbolic to legitimize, Hoffman takes ritual as an entry point directly into the midst, the incoherent centre of sorrow.

“Seventeen’s the number,” Hoffman repeats, “One is for one, and seven is for doing.” With childlike insistence, he translates a personal lineage of life and death into a number game. “She was born on May seventeen, and died on November seventeen. My Dad was born on April seventeen, my uncle was born on April seventeen, and my grandfather was born on April seventeen. Seventeen’s the number. One is for one, and seven is for doing.” Seventeen, we are told, is the number of Phil’s hockey jersey, and of his seat on a plane, and it is the number entered in his log book on the day an elephant fell down at the Rotterdam Zoo. Seventeen is just a number, a minor detail easily discounted in the rush of daily experience. But in Phil’s efforts to account for a series of happenings from the midst of bereavement, seventeen becomes the number, the numerology of loss.

Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home. Your house is on fire and your children are gone.

Hoffman’s method is that of reiteration without redundancy; loss, we are reminded, is never just this loss. In ashes we learn that Hoffman is once removed in the birth order of his siblings from an older brother who died as a result of a miscarriage. Because the child died in utero, the priest refused to perform the funereal rites that would have legitimized this life in the eyes of the church. But funerals are meant for the living, and this disavowal prompted a loss of faith that would sever Phil’s father’s commitment to the church. Later, this man would have another son who would also be named Philip.

Good mourning, in Freud’s terms, keeps people moving on, keeps them in time…

— Adam Phillips, Darwin’s Worms

What becomes of grief that traditional practices of mourning cannot, or will not, contain? Ashes suggests that ritual serves us less as a remedy for grief, and more as a glimpse of ordered time from outside the midst of our daily reckonings with loss. When her mother died, Ann Carson scanned the pages of Virginia Woolf’s diaries in search of something, following Woolf’s own premise that there is pleasure to be derived from “forming such shocks into words and order” after the fact of Death. (165) On the day after the funeral Carson sat at her desk, books spread out before her, looking not for meaning, but for the comfort of structure. I turned to Carson the week I was finishing this writing, the day I had to pause, unexpectedly, to write a eulogy. How can I write my uncle’s life? I wondered, barely upright before a blank screen, caught in the midst of this cruel death, of my memories, his personal life, this public declaration, the faces of my family, my anguish, my rage.

He didn’t just die, he was taken.

Sudden death doesn’t begin to feel real until you see its impact etched across the faces of the people standing directly in front of you. Or, as in the case of my uncle’s death, until I read the horrible truth in what would otherwise have been an ordinary newspaper headline, on an ordinary day. Even then, these were cues that only hinted at what I should feel. Everywhere it said that my uncle was gone, but I could not write of his life in the past tense. I could not write “My uncle was a committed painter for over three decades.” In writing that “he has been painting all my life”…has been, and will be, I clung to the present perfect, the tense of continuity. I do not release him, my uncle’s friend choked from the podium on the day of the funeral with an urgency that cut through my carefully measured sentences, my own attempts to fashion the inarticulate expression of my grief. With those words came another break in time. If mourning requires our participation in the flow of time, ashes insists that we live with death in capricious ways that exist outside of this ordered progression. Perhaps learning to live “from the inside out” means learning to live while dying at the same time – learning to live with death and not despite it. Loss, it seems, is a persistent presence.

Works Cited

Carson, A. Men in the Off Hours. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Freud, S. The Interpretation of Dreams. Trans. James Strachey. London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1991.

Originally published in Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom/Sandlos, YYZ/Insomniac Press, 2001.