An interview by Mike Hoolboom (2001)

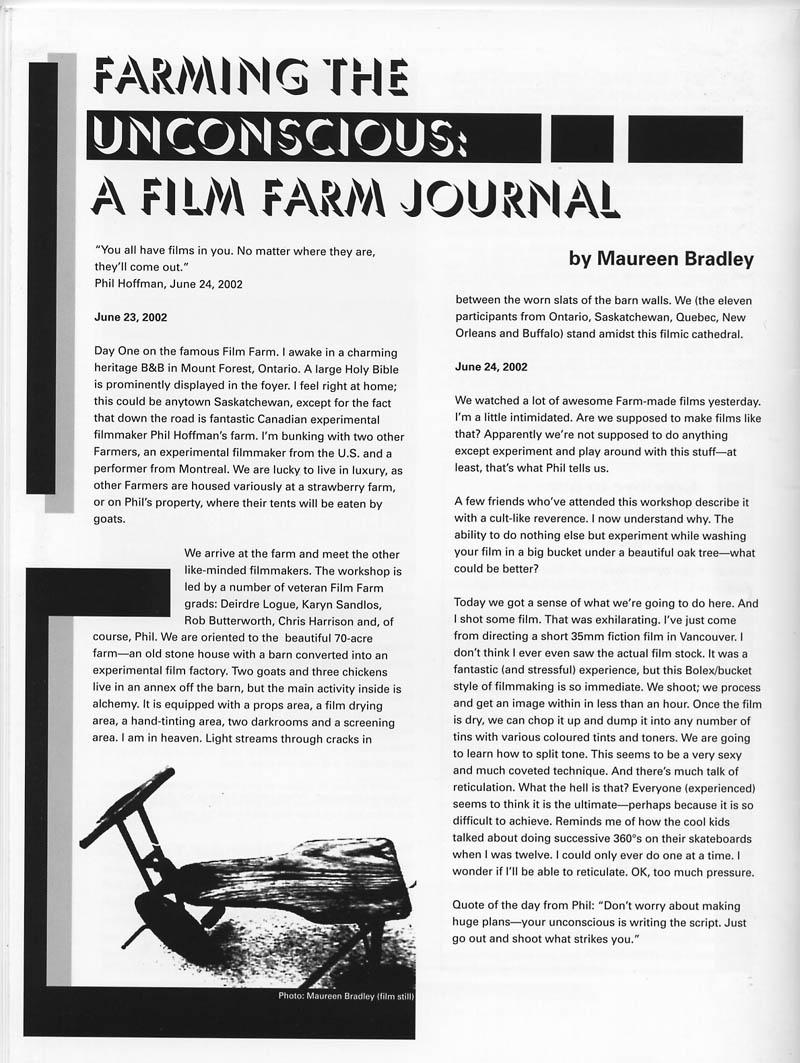

Philip Hoffman: After finishing the autobiographical film cycle I wanted to play again. I brought a super-8 camera along with me to Banff in order to do some sketching. I began exposing a frame at a time while zooming, or moving the camera. The result was a Cubist kind of taking apart of the world. It splays the frame, making the image move. Because of its extreme speed, it is necessary to slow the image down afterwards, controlling the speed via re-photography on the optical printer. The lightness of the camera allowed me to play along with my subject in a musical way. This kind of shooting, or being in the world, marked the end of one kind of working, which was much more personal and traditionally ‘documentary.’

MH: Why was it important to break the space up?

PH: It was in the air. The Berlin Wall had fallen, film had become media, computers were everywhere and fragmentation ruled. The cycle of personal film work I’d finished allowed me to travel and show the work, and Chimera (15 minutes 1996) was the result. It was photographed in Banff, Finland, Russia, Egypt, England and Australia.

MH: Despite lensing for years all over the globe, your shooting style is very consistent.

PH: I felt electric. Like I was touching eternity. These camera gestures create rhythms at the speed of light following an inner-outer sympathy. I was doing a fair bit of inner work at that time—trancing, meditation, yoga—so what was coming to me in image was symbolically meaningful. I had my own narrative, no matter how abstract it might appear to others, but instead of people and places which are a part of a social world, it became another kind of journey. Chimera began in 1989 during the Banff residency and took seven years to shoot and edit.

MH: The shooting blends one place into another.

PH: It shows a world breaking down, and the images express the energy of change. The film doesn’t insist that market people in Cairo’s Khan Khalili and London’s Portabello are the same, but that they share an energy related to colour, shape and form. That’s why some of the film is abstract, to evoke these pleasures of sharing.

In Technilogic Ordering (1994), by contrast, the fragmentation is political, re-working media images of the Gulf War. The collisions mean more because lives are being lost, along with their representation. This sketch of Chimera is simply one way to experience the world. As a viewer you’re only moving forward, like the stream of images that come to us through TV, or the Web. Chimera is a representation of that way of being in the world. Gathering speed. But in the third and concluding part of Chimera I finally go back, and this return offers a critique of the first two sections where each image replaces and erases what’s gone before. In the final section a man plays electric piano in a Russian square, and this is intercut with scenes from a Finnish rave, and the great rock Uluru. Uluru is a sacred aboriginal site which I photographed from a distance. It stands boldly through it all. This movement finally brings us back to making pancakes in the kitchen, because despite virtual velocities and cyberspace, at the end of the day you have to go home and make supper.

I had a lot of trouble finishing the film, in finding the shape for these sketches. I finally returned to its original idea, which is contained in the title. Chimera is an animal in Greek mythology which combines the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of a serpent. For the first time in my making, I didn’t have a narrative to hang the structure on, so I was guided by myth, and the beast’s embodiment of diversity and fragmentation. The first section begins with a roar on the soundtrack and proceeds with an accelerated drumbeat and a scream, which I associate with the roar of a lion. The second section has a very ethereal soundtrack, which is the goat on the mountain, ‘up in the clouds,’ where he finds his place. The final section is the serpent. It is filled with sibilant chanting which brings on transformation.

There were many things in my life that I pinned to these scenes. They are returning now in my making because I couldn’t deal with them at the time. I encountered three deaths while shooting this way. The deaths are not shown or even alluded to in these films, but they lie underneath each of them. Waiting.

Chimera‘s original super-8 footage was being blown up to 16mm by Carrick Saunders in Montreal. I gave him a call to see how it was going and his wife answered. There was some commotion—she left the phone and didn’t return. I phoned later that night and discovered he’d had a heart attack and passed away.

MH: He died while you were on the phone?

PH: Yes. And you don’t know why you’re part of it. Of course this is an awful tragedy for Carrick’s family, but I didn’t know him. As a witness to his death, I felt I was being given a gift, and that I had to do something with it. I just wrote it all down in my journal, but couldn’t figure on how it would become part of Chimera.

In the second instance, I was crossing a bridge over the Thames, just coming out of the Moving Image Museum where I’d shot their history of cinema exhibit. I was blurry eyed. I stepped out on the bridge where a stranger looked me in the face, got up on the bridge and jumped. I spied him through the cracks, already going underwater without a struggle. Dazed, I wondered if I should film him. And didn’t. A man came by and asked if he’d jumped. A woman arrived from the other side of the bridge and said she’d call the police. That’s when I came round. I’d been stuck in that existential moment where you see someone who wants to die. Do you let him? Should you do something? Can you? I ran to the other side of the bridge and met up with a policewoman who didn’t have a walkie talkie. I kept running until I found another cop who said they’d got him. A pleasure boat had come by and picked him up. What a coincidence, this man wants to die but a boat chances along. I asked the cop if he could let me know what happened, and that night I got a note: “The bloke who jumped in the creek is alright.” Both these events made me think about death, and how little control we finally have.

MH: Tell me about Technilogic Ordering (30 minutes 1994).

PH: The Persian Gulf War was a made-for-TV affair which filled me with anxiety. I watched the war with some of my students at Sheridan College where I was teaching. A couple of them—Heather Cook and Stephen Butson—began to collect images as a way of thinking about the broadcasts. It’s like when you have a lot of nervous energy you go for a skate. You have so much anxiety watching this stuff and you have no control over it.

During our gathering I found a VCR with a computer chip that fragmented the image into Muybridge-like box-frames. This machine allowed you to play the image, changing the size and number of the boxes onscreen—do you want 9, 400 or 1600?—and scroll them from left to right, like reading or media literacy.

We collaged some of the different footage we’d collected, inserting commercials, movie fragments and sports into news broadcasts of the war. Among other things, we wanted to show the difference between Canadian and American coverage. While many Canadian commentators questioned the necessity of the war, the Americans were blindly patriotic. As we discovered later, all the war footage had been cleared by the Pentagon, so it appeared bloodless and techno-centric. It was mayhem at a distance. The boxes were a visual way of commenting on the reports, making patterns out of this destruction, and allowing the pictures to critique themselves.

The montage featured many heavy-handed collisions. Kitchen cleaners were juxtaposed with images of the Iraqi army being ‘cleaned up.’ Airplanes from the Wizard of Oz smoked messages across the sky: “Surrender Dorothy.” There was a nationally televised football championship going on at the same time which blurred the line between sports and war. Both featured the same mass hysteria. Once the editing was done, the video footage was transferred to film because in order to really see television you have to look at it somewhere else, in a movie theatre for instance.

MH: Like much of your work in the nineties, this film began as a collaboration.

PH: After my personal work in the eighties it was time for the author to die. I wanted to relinquish control, explore ways of making that would expand the palette. In the early nineties I started three projects that had in common sketching, collaboration, and smaller format technologies (other than 16mm). With the help of Vesa Lehko and other friends in FinlandChimera was turned into an installation. Technilogic Ordering was made with Stephen Butson, Heather Cook and Marian McMahon, who naturally helped with all of them.

In Opening Series I collaborate with the audience by offering a film in parts, each in its own painted box. I ask them the audience to arrange the boxes in the order they would like to see them on screen. The film not only runs differently each time, but provides a picture of its audience. Opening Series arose out of questions of inter-activity, which too often means people watching computer screens instead of relating to one another.

Following Opening Series are three collaborations: Kokoro is for Heart with Gerry Shikatani, Sweep with Sammi van Ingen and Destroying Angel with Wayne Salazar. By the mid-90s, I’d committed to hard-core collaboration.

MH: Kokoro is for Heart (7 minutes 1999) has a feel of daily ritual and naming.

PH: I met Gerry Shikatani at Sheridan College where he worked in the writing department. Gerry’s a poet, a Nichols protegé. He writes sound poetry, novels, and food reviews for the dailies. One morning Gerry came up to the farm and we went for a drive, not thinking about making a film at all. We wound up at a gravel pit, and I pulled my camera out of the truck while Gerry interacted with the space of the pit, moving rocks and branches around. I shot two rolls of 16mm reversal. When I got the footage back I noticed the registration pin was slipping, so there were periodic stutters in the image. Trained as a cinematographer, I saw these as flaws, though Marian said they were like Gerry’s voiced poetry. He works with the structure and gestures of language, and the flipping frame reveals the structures of vision strained through the machine.

I optically printed the whole film one to one and two to one. So each picture had a double, one for each of its makers. Then I cut the film into twelve parts, and put them into twelve separate boxes for Opening Series 3 (7 minutes 1995). The audience would choose the order they’d be screened in. I made the paintings for the box covers by using natural materials like seeds and sunflowers, along with family photographs and paint. Then I put a blank canvas on top of the painted ones, laid them on the ground and drove over them with my truck, so every picture is doubled as well.

As an interactive work, the film began its life as part of the Opening Series experiment where the audience effected the order of the film by arranging the boxes. We also ran it as a performance at Cinecycle where Gerry sat in front of the projected image rapping out his sound poetry. Later, we fixed the order of the film, made a final print and renamed it Kokorois for Heart. The performances served to find a satisfying, fixed order. But it can still run as an open ended work in the performance setting.

‘Kokoro’ is the Japanese word for heart, or life force. Here, it’s the heart of the land, speech or breath. Gerry is shown as part of the landscape but separate from it, and his words on the soundtrack (a blend of Japanese, French and English), are a way of knowing or naming the land. They’re the language of the land or a landscape of language.

MH: Tell me about Sweep (30 minutes 1995).

PH: One of my interests in making the film was to go to Kapaskasing because that’s where my mother settled when she first came to Canada. My grandfather, Driououx, came toCanada to work as a lumberjack, eventually ran a poolhall and pushed moonshine on the side. The area they lived in was actually called Moonshine Creek. My grandmother, Babji, ran a rooming house. I asked my mother to recollect Babji’s stories for the film, which she does while looking at family photos. One of these shows the family gathered for Christmas dinner. Mom says this picture makes her feel happy, because at Christmas everything would go well. But I knew from my own growing up that visits to Babji and Driououx’s would always start in fun but often end with a plate of food hitting the kitchen wall. I pose these questions to my mother through narration, and her answer is evident in the grain of her voice. The violence and abuse in the household remains in her trembling speech. This is where our forgetting, and the things we care not to tell, come to reside.

This makes me think of Marian’s work, how the past lives in the present. The fears we don’t get over become part of our everyday life.

My mother’s image returns at the end of the film when I zoom in on her, followed by a zoom on me, as a reminder of that repressive pain, which flashes forward from the beginning of the film to its end, as suddenly and ferociously as the past takes over the present.

MH: Your collaborator is Sami van Ingen and his journey is also a personal one.

PH: Sami’s great grandfather was the American documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty. He’d made ethnographic ‘classics’ like Nanook of the North, which was shot in Canada. While it is considered one of the first verité documentaries, most of the scenes were staged and rehearsed. And it offered a particularly white view on native practices, made in a time when white meant ‘objective.’ Sami wanted to return to some of the places that his grandfather had been in order to deal with this part of his family’s history.

While we were making the film, a feature-length drama was released about Robert Flaherty, which reveals a love affair he had with a native woman. Everything was suddenly out in the open. Sami and his family already knew this, but no one dared to speak about it. They were keepers of the legend, the great genius, the family name. Our film begins with a suggestion that we will hear details of family history, but Sami didn’t want to go further in that direction, so the film arrives at more general conclusions. We used archival home movies showing white men’s journeys to appropriate the north. Sami’s great-grandfather, Robert Flaherty, was just the most famous person who went up there. So while we couldn’t speak of the family legacy, we could show white men hanging around the native camps, and the effects they had. These scenes are intercut with shots of Sami and I dozing around a pool on our way home amidst spring blooms, implicating us as part of another wave of white explorers. The film has a strong visual thesis, but parts are missing. It’s like the deaths I encountered while making Chimera, real life overwhelmed its representation.

MH: The film shows the two of you traveling north by car, meeting people along the way, and entering a Cree reservation. This journey ends when one of the native guides takes you across the water to Fort George.

PH: Fort George was one of a series of British forts built in the North, and Flaherty would have traveled through there. The Fort is gone, but we found an old Hudson Bay Company trading post still standing which we filmed. I say in voice-over, “You’re not going to find your grandfather here. It’s gone now. It’s over.” Around the building we discovered a lot of beautiful driftwood. Earlier in the film we showed the dam, and talked about how the need for hydro-electric power overwhelmed Native protests, and how their burial grounds were flooded because the dam raised the water level. This driftwood is also a result of the dam. These are the bones of the forest, the ruined culture. The driftwood was shot in high contrast stock, with the haunting call of Canada geese in the distance. Then we have a lunch of canned fish and tomatoes which we film, because all we can do now is film ourselves. We’ve come all this way to shoot the making of a sandwich.

During the trip all of the native people we met asked us to film them. During the dam protests so many white journalists had been up to visit they were used to it. They’d even built a motel just for visiting politicians, and had a huge teepee as the local supermarket! We always refused, saying we don’t want to tell your story, this is up to you, and it always has been. So the film’s critique of ethnographic filmmaking shows the failure of white culture to integrate, proposing a movement alongside instead of the usual pictures of control.

At the end of the film, during dinner, I showed our native host Christopher Herodier how to use the camera, and he shoots us eating. I left him with the camera, saying, “Give me a surprise.” When we got back to the city and processed the roll we discovered that Christopher had filmed a teepee against a backdrop of new housing, and then the two of us against a sunset, slightly out of focus.

When the film was finished, Petra Chevrier invited Sweep to screen at the YYZ Gallery. I called Christopher and asked if we could show our work together. He had made a videotape called Chiwaanaatihtaau Chitischiinuu (Let’s go back to our land). It shows a Cree protest against the building of another dam, the canoe voyage from Fort George to Great Whale, the singing and the outrage. The two pieces played together for a month and it was very satisfying. It reflects our approach of living cinema.

MH: Can you tell me about the title Sweep.

PH: To shoot the drive northwards we rented a motor that ran the camera very fast, giving us super-slow motion. At the head of the shot the motor’s still gaining speed, so you get a fast motion which is overexposed, which then turns into slow motion at a regular exposure. This gives a sweeping motion to the image, a sweeping of landscape and driving. ‘Sweep’ is also sweeping the road clean, trying to start over again, sweeping away Flaherty.

MH: Destroying Angel (32 minutes 1998) features another collaboration, how did that begin?

PH: I met Wayne Salazar in Australia in 1991 at the Sydney Festival. The curator Paul Byrnes had invited me show all my work. In Sydney, Paul would take you to supper every night, with a small group of filmmakers and curators, and Wayne was party to that. It was a marvelous time. Soon after the festival I visited Wayne in New York, and a while later he called to tell me he’d contracted AIDS and was very sick. He was going to tell his mother who lived in New York State, so I invited him to come up to the farm and relax and meet Marian. That’s when we started shooting. I don’t know how these things start. Maybe it’s just that you’re always shooting film, and when people come you keep shooting and then films start.

The farm reminded Wayne of his rural youth, the day trips he used to take with his father who worked as an insurance salesman. Wayne’s bad health made him wonder how long he was going to be around, and he felt compelled to deal with his father who had abused him as a child. They hadn’t seen each other for years, but Wayne decided to go see his father and tell him he had AIDS. This all became part of the film. The first weekend he came he got along well with Marian, and they spoke about personal histories, and her themes of remembering and forgetting. He was very sick then, and taking a lot of pills. The drug cocktail hadn’t been introduced yet, so he was tired and depressed. It was Wayne’s idea to make the film and I felt my role was to assist. He’d made a short video about Cuban artists, had seen a lot of films as a curator and had been painting since art school, but really had no experience making personal film work. Which is fucking hard. During the making, I felt I was back working on Road Ended because the struggles were the same. Road Ended took seven years to make, trying to give shape to these concrete bits of memory, working without a script, and letting the camera respond to experience as it’s happening. I stayed patient, trying to help give Wayne an outlet. I learned more about his struggles of growing up gay, dealing with his macho father’s disappointments, and how he and his lover Mickey were finding a way to live.

It began as a film about our fathers, but it quickly became clear that mine was no match for his. The stories of Wayne’s abuse created too much of a contrast to my father’s sympathetic parenting. I shot sequences and told stories which were part of an early cut, which might one day join another film. But there was so much anger and need on Wayne’s part that I had to withdraw. The decision was made when my partner of twelve years, Marian McMahon, was diagnosed with cancer, and a week later, during a biopsy, she died. We stopped making the film, and when I climbed up out of the hole, that’s when I moved my voice out of the film. I needed to make my own film about Marian, her life and the grieving. Marian was already part of Destroying Angel, asking Wayne questions on video about his meds, and AIDS, and everyday life. Wayne felt close to her and asked if her story could be developed more in the film, if we could show this passing, and I felt that would be right.

MH: You show Wayne and Mickey getting married.

PH: Back in San Francisco, Wayne got healthier, which was partly the drugs, diet and exercise. But the film had a lot to do with it as well. Wayne and his partner Mickey decided to get married. Mickey is Austrian, so an Austrian TV crew arrived to shoot them for a news program on San Francisco gay life and marriage. And I thought, yes, we have to have this in the film. Their reportage was typically television. It opens with a shot of the Golden Gate Bridge, then moves into the gay bars, and sexual activity and dancing and high pitched screaming, but in our film, we inserted a shot of Wayne and Mickey walking down the street buying flowers. Very everyday. It’s a nice moment because it shows how television creates stereotypes.

MH: Why did they want to get married?

PH: They were in love of course. But I think it was a political decision as well. In a culture that doesn’t accept their sexuality, it was a step towards gaining the same rights as heterosexual couples.

MH: Wayne speaks to his father surrounded in darkness, directly to the camera, outlining a history of ignorance and abuse. But when we meet his father at the wedding he looks so benign.

PH: The film reveals how the monsters of our past live in us. He’s become an old man, no longer shouting abuse at Wayne. But it doesn’t change what he did. He hurt Wayne, and neither of them could deal with it. They held onto this pain for years. At the ceremony, Wayne says it hasn’t always been easy with his father, who then breaks in and proposes a toast to Wayne and Mickey. He says that he’s from Guatemala, a culture where gay people exist only in the closet. And then he wishes Wayne and Mickey happiness in their life together. But it took the making of our film to release this fear. It’s Wayne that’s done the work to recover his past, and the evidence of this work is Destroying Angel. While the early passages of the film are drawn from Wayne’s point of view, the ceremony at the end is shot in a verité style by the Austrian video crew. Finally, we’re seeing something outside ofWayne’s frame. He’s no longer telling his story using voice-over. We enter another side of him, and this adds in a profound way to the information we get about his relationships.

Wayne called me last week, a year after his father died. He said, ‘I don’t recognize that guy in the film.’ He was referring to himself. People use different tools to create change in their lives. Some use work, or alcohol, or art. Wayne doesn’t need to talk about his father that way anymore. This is a familiar feeling for me. passing through, for instance, was a grieving for my grandmother Babji. You hope these rituals of filmmaking resonate for others.

Marian’s death is revealed in Destroying Angel and people say, ‘you must find that hard to watch,’ but I don’t. I love her images, her voice and her writing. After Marian’s death, while looking up references to bring her Ph.D. thesis to completion, I dwelt for hours on the small hand-scribbled writings she left on the texts she was reading. No matter how esoteric or academic the text, her response would always tune in the personal, the everyday. She came back to life for me through her writing. The film I’m working on now attempts to deal with the traces she’s left behind, so that I might better understand our time together and learn something about death and life. The dead carry on longer than the living, and it seems that the force of a life lived is stronger once it ceases to exert itself… its silence and mystery.

MH: The title Destroying Angel suggests an angel that returns to wreak vengeance, a once purity that’s now armed.

PH: It’s also a mushroom, one of the most deadly and poisonous. The poison is the virus, which brings pain and suffering, but also transformation and change and growth. There’s an eating sequence in the film shot up at the farm where Wayne is making us dinner. In the early nineties there was still such a fear of casual infection, you know, he could cut himself and infect us, but instead there’s only celebration. We’re living right now, the camera’s floating around the food and we’re having a ball in the face of it all.

MH: Much of your work in the 90s is more hermetic and difficult than your autobiographical cycle. What would you say to those who feel your work, along with others in this small field, is willfully self enclosed, unnecessarily obscure, interested in formal issues in a medium which itself is coming to an end, and on the other hand suffers from solipsism andnarcissism.

PH: Yes and? It lives with me and that’s what is important. Often circumstances collect around you and you have to make the film as well as you can without knowing why until later. Sometimes you get a song out of it, sometimes a mumble.

MH: Is it important to finish work or is it just the process that’s important?

PH: I need to bring everything to some kind of completion. I learned from my dad how to start and finish things in the factory when I used to make boxes every day. Screening your work and receiving feedback is an important part of the process. We experimentalists may not get the TV audience but that’s alright. Our work has a different purpose. We’re the people behind the stage sweeping up the old act and getting it ready for the new show.

People who try and push boundaries are part of a lineage that’s a much thinner thread than CNN or Cineplex, but it’s continuous, it’s a living history. We’re carrying this on, and maybe I’ll make just one film that’s important, that will have an effect on people. I hope I haven’t made it already. If I’ve always held on to the personal it’s because I believe that what I’ve lived has a shape, an organic world that can be shared, through film, with others.