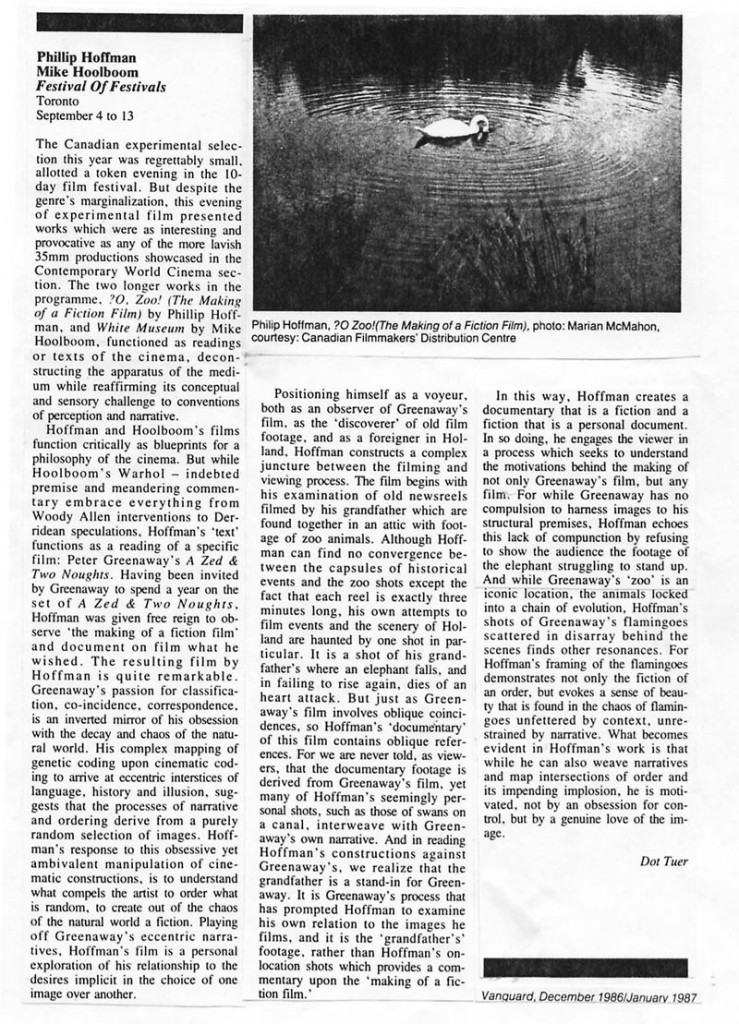

by Dot Tuer

Vanguard, December 1986/January 1987

Category Archives: Reviews & Articles

With Genie-nominmated under his belt, filmmaker now hopes for recognition

O Zoo: The Making of a Documentary Film Music

by Tucker Zimmerman

I want to take you into the actual process of working on music for a film. I want to do this with a piece of music that I am not so pleased with. This is intentional. I had a lot of trouble with this film music. The film was made by Philip Hoffman, a Canadian filmmaker. In Canada, Phil met Peter Greenaway who liked his work and invited him to come to Holland to make a documentary on the shooting of his new film which was A Zed and Two Noughts. Phil shot his documentary in the summer of 1985, and at the end of that summer he came to me from London, where he had met a mutual friend who told him of a composer living in Belgium who writes a similar kind of serial music that Greenaway used in his film.

At this point Phil and I didn’t know each other. This was our first meeting. One of the things I sensed about Phil was that for me to write successful music for his film I would have to become his friend. This was not as drastic as it may sound. We did become friends—and not only because of the work we did on the music for this film. However, everything that Phil does is personal. And in many ways, at the start at least, this was a difficult situation to be put in. It is much easier if the relationship between filmmaker and composer is detached. Then it is simply a transaction.

As it turned out, Phil had four days to spend with me. And for the first three days I think I drove him crazy because I refused to talk about music, film music, or even the specific work at hand. So we had conversations about other things. I had him doing other things, such as playing baseball (he is not the first filmmaker I have subjected to my baseball test, nor will he be the last—I can tell a lot about a person once I get him or her out throwing a baseball). Later Phil told me that he had serious doubts about my own sanity, about my capabilities—whether I knew how to write music for films at all.

Finally, on the last day we got down to talking about his film. We went to the RTB in Liege where I had the use of a Steenbeck, and I saw the unedited footage on the small screen. After the screening, I was not sure I could do the job. I must say that when I look at most films the first time, I know what needs to be done and how to do it. With Phil’s film I didn’t know what I was looking at. I’d never seen this kind of work before. It was not just a question of what kind of music I would write, but if I could do it at all. I wasn’t sure I was the right person for this job.

One of the first things we discussed was the music of Michael Nyman, the composer of Greenaway’s film. Phil thought that my music should somehow connect with Nyman’s. He wanted something with a mechanical nature to it. My first reaction was that Phil’s film did not need minimal music, that it was not a ‘minimal’ film, that it needed another kind of music.

Another element that became important was that this was the first time that Phil had worked with a composer. He had used music in some of his previous films—one features a saxophone solo— but it was done without a great deal of preparation. This new film would demand a composed score.

So understandably, Phil was a little nervous about this new adventure. And he reacted by wanting too much control over the music. He had these elaborate charts. Music should be here and music should be there. Which is OK. If a filmmaker says he wants 37 seconds of music at this point here, and another piece of music over here for 13.5 seconds, that’s no problem. But if he gets too specific about how all these various pieces should be related—and not only in musical terms—then the job becomes too restrictive. The composer is shut out of the process and his input is denied. This is a trap that Phil fell into with his unbelievable schemes which I couldn’t decipher. And this is getting back to what we talked about before about trust — learning to trust the composer and letting him get the job done. Phil couldn’t trust me, and as it turned out, he found he couldn’t trust himself either. In any case I agreed to do the music, still unsure I could, thinking maybe that I was jumping off a cliff.

Phil returned to Canada and then began a series of long telephone calls. The plans kept changing and the phone bills kept going up. We exchanged letters with a lot of conflicting decisions. We were wasting time. He told me later that he was confused about the music. He admitted it.

(Later, when I did the music for his next film, he gave me total freedom and the music came out quickly and we were both pleased with the result.)

Anyway—concerning the film we were working on back then—the film presented certain problems to me that I wasn’t sure how to solve. It was supposedly a documentary about the making of a feature length fictional film. It’s called ?O,Zoo!, and subtitled: The Making of a Fiction Film. But what Phil did was a lot more than that. He created a fictional documentary. A documentary is one thing, but a fictional documentary is something else. For example, let’s take the opening sequence. The old footage that his grandfather, who was a newsreel reporter, had shot a long time ago and which Phil discovered in his attic. As you quickly find out, there is no grandfather, there is no attic and there is no old footage. You begin to see that this is all something that Phil has created himself. It is imaginary. Then you start realizing, you say “What’s going on here?” And what is going on is that he’s playing around with the documentary, with its traditions, while making a fiction film.

Now for the music. Phil is saying ‘mechanical’ and I still don’t know what to do. I’m struggling, trying out this and that kind of music and unsure of what I’m doing.

Another problem was that Phil had shot some of the same things Greenaway had shot and would probably use in his film—from a different angle and not all of the time—for as you will see, Phil spent a lot of time with his camera doing other things, which at first sight might appear to be unrelated to the Greenaway film, but which in fact are not. You have the scene with the tigers. What does Phil do? He goes around to the back of the cage where the tigers are waiting and gets into a conversation with two boys. Those scenes Phil shot on set were the same as Greenaway, and to which Nyman would probably write his own music. So the problem here is twofold. First, I don’t know what music Nyman will compose, and second I must compose my own music for a different ‘angle,’ just as Phil’s camera was shooting that scene from a different angle.

Finally Phil and I established the idea that we would start with ‘source’ and move away from that and progressively deeper into the illustrative (or a non-real music). I was talking earlier about sound effects and how music can be mixed with good result with natural sound. So we started with the water sprinklers. Tapping and making a spraying sound. Of course this is not the real sound of water sprinklers. This is the noise generator on my synthesizer making a ‘false’ sound effect. This tapping allowed me to establish the pulse of the first piece and I moved on from there, inwards, into the illustrative. The plan was then to get progressively deeper into the illustrative until you reach the end where the boy is walking with his grandfather, coming home from a fishing trip, and you’re hearing music that is almost straight out of a Hollywood film from the 40s or 50s, if not in colour at least in style and gesture. It has the same nostalgic, or sentimental type of feeling to it, but of course its function here is quite different. Its function is to make you aware that I’m fooling around with these emotions, that the music is almost a parody of itself. So I am playing around with ‘false’ music in the same way that Phil is playing around with a ‘false’ documentary.

So I hope you get the idea. It’s a very complex thing. Let’s look at the film.

On (Experimental) Film

by Barbara Sternberg

…speaking to Philip Hoffman about his summer in England ‘apprenticing’ with filmmaker Peter Greenaway (Draughtsman’s Contract, The Falls): Philip was especially interested in Greenaway as someone who has bridged the gap between shorter experimental films and (low-budget) feature-length works accessible to a broader audience. Philip wanted to see how Greenaway operates within the commercial industry, yet maintains his control; how he can make films for the ‘public’ without compromising his conceptual and visual concerns. Philip is an independent filmmaker (On The Pond), The Road Ended at the Beach, Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encaraclon) and a freelance cinematographer. He worked on Kevin Sullivan’s Krieghoff and Megan Carey. And recently on Richard Kerr’s On Land Over Water. His films have been screened at the National Gallery, Ottawa; Zone Cinema, Hamilton; The Funnel, Toronto: Museum Fodor, Amsterdam; London Filmmakers’ Co-op, England. Philip teaches part-time in the Media Arts Department at Sheridan College.

He first met Peter Greenaway at the ’84 Grierson Seminar where the idea arose of going to England to observe Greenaway shooting his newest film Zed and Two Noughts while Hoffman made a short film of his own. Philip speaks highly of the experience – the opportunity to look over the shoulder of cinematographer Sacha Vierny, to follow the filmmaking procedure right through, to see what worked, what didn’t, how adjustments were made, when to let an idea go, and generally how communication was effected. Philip is still glowing from the warmth of his reception. Besides access to the shoot and the use of his editing facilities, “more than just that,” says Phil, “Greenaway appreciated that I am trying to be inventive in film against all odds. He even took prints of my films and showed them around—that kind of cooperation!”

Interest was shown by Kees Kasander of Allart’s Enterprises (the Dutch producer of Greenaway’s film) in Hoffman’s short premiering along with Zed and Two Noughts at the London Film Festival in November. Philip returned to Canada at summer’s end with his film? O, Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) in rough-cut stage and with this deadline in mind.

Unfortunately, he won’t make the festival. Although the film had been accepted into the N.F.B. PAFFPS programme, Ontario Region, Philip was reminded in September that this is a Low-Priority Programme—the film would he printed when there was time, perhaps three to six months. He was also told that he would have to reapply for completion money and that the programme is ‘on hold’ for now. Philip was disappointed by a system that is supposed to help, but even more by the lack of interest, respect or enthusiasm shown—they didn’t even ask to see the film!

The N.F.B.’s aid to independents IS helpful, but the whens and hows are always uncertain – and that’s less than helpful. Philip has decided to apply to the Arts Councils and hopes to complete the film for the Berlin Festival in February.

(Originally published in Cinema Canada 1985)

*Footnote: When Hoffman tried to use NFB facilities to edit his film, he was told he would have to wait his turn as the editing machine were all in use. Meanwhile, Gary Popovich another PAFFPS recipient, and partner in experimental crimes, invited him into the space he was given. Hoffman was surprised to see many machines on the floor unused, so the film was eventually edited at the NFB, though they do not know that. This was the last film Hoffman made with support of the NFB.

Deception and Ethics in ?O, Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film)

by Michael Zryd

Like all “anti-documentary” films–those which call into question the documentary genre’s easy claims to epistemological certainty–Phil Hoffman’s ?O, Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) must be approached in terms of the particular documentary form it questions and the particular context of its maker and making. In ?O, Zoo! Hoffman plays off the filmic projects of John Grierson and Peter Greenaway to furnish an admirably tentative meditation on two knotted ethical problems of film form. One concerns the way that sound/image constructions attempt to dictate meaning in conventional documentary. The second takes on film’s photographic claims to certainty in one of documentary’s favourite subjects: the representation of death. These intersecting planes of subjectivity and convention, and these ethical meditations, create a turbulence underneath the disarmingly simple and elegant surface of ?O, Zoo!, a turbulence which accounts for the emotional resonance of its ending(s), and for its troubling aftertaste

Founding Fathers

?O, Zoo! is, in some ways, atypical of Hoffman’s work, being his most directly analytical examination of a set of film conventions. In films like On the Pond (1978) and passing through/torn formations (1987), a much more meditative and lyrical mix of image, sound, and narration offers an intensely personal view of childhood and family. Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) deals with Hoffman’s reaction to an isolated incident in Mexico, the death of a small boy in the street. The Road Ended at the Beach (1983) is a diary-quest following Hoffman and some friends “in search of the Beat generation,” as they trek across Eastern Canada to find Robert Frank. All these films share an explicit personal voice (either in voice-over or written text), a voice by turns matter-of-fact, self-ironic, poeticized (here, often with less certain success), but always direct and Hoffman’s own.

Robert Frank’s influence is central to the development of Hoffman’s sensibility. Aware of the filters the apparatus imposes between film and experience, the filmmaker seeks direct contact with his subjects. With Frank, Hoffman shares a concern for the articulation of the filmmaker’s subjectivity, and for the camera’s power to record and reveal events. Unlike Frank, however, Hoffman’s approach is tentative; as Blaine Allan puts it, Hoffman places himself “on the temporal and spatial edges of an event” (1987:91). In The Road Ended at the Beach, Hoffman ironizes the Frank persona to point, finally, to the folly of attempting to recapture the immediacy of the Beat generation’s attitude to “experience.” When he finally finds Frank in Nova Scotia, Hoffman is told, in a low key (and utter) deflation of his quest, that Kerouac is dead, the Beat generation is over, go home.

If The Road Ended at the Beach can be seen as Hoffman’s attempt to exorcize the ghost of Robert Frank, ?O, Zoo! finds him tackling two more figures of influence: John Grierson and Peter Greenaway. In ?O, Zoo!, they are paired as the Founding Father and the Grand Inquisitor of the institutional documentary. Hoffman links the two unmistakably, though not explicitly, in a passage in the first sequence of the film:

“That spring, I went to the Netherlands to make a short film around the making of a fiction film. I met the director in a seminar in my native country in the fall before my grandfather’s footage was found. This seminar, an annual tradition since 1939, is devoted to the documentation and categorization of all types of wildlife species ever captured on film. The seminar grew out of the same institution that employed my grandfather as a newsreel cameraman. I can still hear my grandfather’s remarks about the founder of the institution, as he put it, “that old battle-axe.”

The “fiction film” is A Zed and Two Noughts (1985); the director, Greenaway. Hoffman and Greenaway met at the 1984 Grierson Documentary Seminar held in Brockville, Ontario. The seminar that year, entitled “Systems in Collapse,” was devoted to the anti-documentary. The Seminar began after Grierson’s death and within the fiction of the first sequence, Hoffman conflates the seminar with the National Film Board (NFB), founded by Grierson in 1939. “That old battle-axe” is an appropriate description of the mythical crusty Scotch Calvinist; to underscore the point, the phrase appears over a close-up of an ostrich’s head. The physical similarity to Grierson is striking.

Grierson hovers as a key figure behind both the Canadian and British documentary traditions, and is thus a point of departure for both Hoffman and Greenaway. His unique legacy as film director and administrator, to the end of an openly propagandistic film product in the service of the state, makes the “Griersonian” mode of documentary a particularly acute model of what Noël Burch calls an “Institutional Mode of Representation” (1979). Certainly, one can identify an NFB house-style with as many stylistics as any Hollywood studio study could muster. Greenaway worked for 8 years in the British equivalent of the NFB, the Office of Information. During that time he produced, as he calls it, “soft-core propaganda” (cited in Della Penna and Shedden, 1987:20) before turning to experimental and narrative fiction modes of filmmaking. Especially in his hyperbolically parodic anti-documentaries, The Falls (1980) and Vertical Features Remake (1979), Greenaway works to great advantage off the solidity and recognizability of the government-issue documentary. Systematic in their astonishing mimicry of form, and profound in the depth of their analysis of the technocratic ideology at the base of Grierson’s form, Greenaway’s films initiate a full-frontal assault on the Griersonian institutional mode.

Hoffman’s confrontation with the Grierson mold and myth and with Greenaway’s analytic project are oblique, even affectionate. ?O, Zoo! adapts the central formal device of Greenaway’s critique–a coherent voice-over ordering disparate images to create a hermetic non-referential fictional universe–to the rhetorical traditions of the narrated personal diary-film of the independent filmmaker. The fiction of the grandfather frames Hoffman’s own penetration of Greenaway’s narrative film production, less to satirize (*1) Greenaway than to harness the skeptical dynamic of Greenaway’s voice-over/image relation. While the extreme artifice characteristic of Greenaway’s later cinema is concentrated into his elaborate visual tableaux, in his earlier films, Greenaway’s artifice is concentrated in the complex counterpoint between his soundtrack (Colin Cantlie’s voiceover narration and Michael Nyman’s music) and “documentary” imagery. Hoffman mobilizes Greenaway’s counterpoint but refuses to capitulate his filmic world entirely to fiction; instead, Hoffman keeps his meditation on events focussed on what he calls “lived experiences”.

Sound Models

In “The Creative Use of Sound” (1933) Grierson outlines his defence of the freedom and power of sound. Clearly inspired by the 1929 “Statement on Sound” co-signed by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Alexandrov, Grierson insists, like the Soviets, that “the final question is how we are to use sound creatively rather than reproductively” (1966:158). Yet, though he maintains the mobility of the sound montage-piece, Grierson prescribes a limit to the possibilities of asynchronous sound:

“Our rule should be to have the mute strip and the sound complementary to each other, helping each other along. That is what Pudovkin meant when he talks about asynchronous sound.” (1966:159)

By invoking Pudovkin instead of Eisenstein, Grierson demonstrates his preference for linear coherence at the expense of a dialectical approach that would expose contradiction. In this respect, when Grierson calls for art to be a “hammer” (cited in Morris 1987:41), he is far from Eisenstein’s “kino-fist.”

Complementary sound/image relations serve the production of coherent, stable meanings in the text. Later in the essay, when Grierson speaks of the use of “chorus,” he says it must be in the service of unity: “By the chorus, characters are brought together and a single mood permeates a whole location” (1966:160). Interestingly, he notes of the “recitative chorus” that “the very crudest form of this is the commentary you find ordinarily attached to ‘interest’ films” (1966:161). 1 Yet even if Grierson favours, at this early point in the 1930s, a voice-over narration “which adds dramatic or poetic colour to the action” (1966:161), that “colour” must not in any way create conflict. Rather, it must enhance meaning. As he said of the general desired effect of the propaganda film, the voiceover should “inspire confidence” not present “problems” (Morris, 1987:45). Grierson’s dislike of Humphrey Jennings’s WWII films demonstrates how the “creative use of sound” must not be in any way disturbing. Moreover, the overarching dominance of the “recititive chorus” in the Canadian WWII documentaries made under Grierson’s command demonstrates how the route of least resistance to a strong propaganda message is through “authoritative narration” (Elder,1986-87: 157).

The complementary voice-over/image relation is the bedrock of the institutional documentary. The image track is arranged to illustrate the narrator’s descriptions and the indexical power of the [**add: photographic] [**sorry to add a word, but not all images are indexical] image is harnessed to the rhetoric of the soundtrack. This places its referential authority in the service of an authoritative voice-over narrator, usually male, whose own vocal performance is coded by standardized diction, pacing, clarity of tone, and coherence. Greenaway’s mimicry of this convention is superlative. In Vertical Features Remake, Colin Cantlie’s “BBC voice” explains the attempts of the “Institute for Restoration and Reclamation” to reconstruct a film by a “TulseLuper.” As names and places appear on the soundtrack, photographs, drawings, and moving images appear on the image track to illustrate the often convoluted but always self-assured narration. The insistence of the illustration is key to the satire; the film cuts to the same photograph of Tulse Luper no fewer than 23 times.

Hoffman’s clearest appropriation of Greenaway’s method of constructing a fiction in fake documentary form appears in the opening sequence of ?O, Zoo!. Instead of attacking the authority of the institutional narrator (Greenaway’s target), Hoffman undermines a different set of conventions: those surrounding the authority of the filmmaker-narrator of the personal diary film. Interestingly, ?O, Zoo! is the only early film of Hoffman’s where he does not read his own narration. Reminiscent of Hollis Frampton’s (nostalgia) (1971), where Frampton has Michael Snow read the voice-over of his most obviously “autobiographical” film, Hoffman puts himself at one remove from the “revelations” contained in ?O, Zoo!.

Sound-Image Relations and Fake Framing

The film opens in silence on a lion roaring–a joke on the MGM lion announcing the beginning of another, more familiar, kind of fiction film. The image is sepia-toned (as will be all the images of this sequence), connoting age. The silence is broken by the voice of the male narrator:

“The footage was found by my sister in my grandfather’s loft. Having been at one time a newsreel cameraman, grandfather knew to keep the cannister well-sealed, and since the loft was relatively cool and dry, there was no noticeable deterioration.”

The voice is flat and deliberate, not a BBC voice but a voice appropriate to a personal diary film. This explanation of the image’s integrity and lack of deterioration makes reference to the filmmaking process, while bringing the viewer into the confidence of the voiceover. The narrator assumes we know that a cool, dry loft and a well-sealed canister will prevent a film from deteriorating. The immediate wedding of image and voice-over, its personal tone, and the reflexive explanations attempt to pull us into the film, consistently set against the institutional film:

“I recalled seeing my grandfather’s old newsreels … There was a marked difference between the repetitive nature of the news film and the footage found in the loft.”

If Hoffman differentiates the “voice” of the institutional newsreel from that of the personal diarist, he also invokes his own tradition: Canadian experimental filmmaking. One shot of the stock footage Hoffman uses has already been incorporated by experimental filmmaker David Rimmer into his film, Waiting for the Queen (1973). The allusion is, first, proleptic of the levels of intertextuality in the film as Grierson, Greenaway, Vermeer, and a variety of tropes of structural film make “appearances” in ?O, Zoo!. More specifically, it refers to the tradition of Canadian experimental filmmaking that interrogates the photographic image. Rimmer, for example, often uses stock footage to study image degradation through looping, so Hoffman’s term “repetitive” is apt. When Hoffman later implies that the NFB is an organization devoted to the filming of wildlife, he makes allusion both to Greenaway’s obsessive filming of animals (and the setting of A Zed and Two Noughts in a zoo) and to the stereotypical NFB nature documentary. The inversion is here complete: within the fiction, the “personal” images of the grandfather are linked, by subject, to the institution of the NFB. Meanwhile, the stock institutional images of the public event allude to the independent experimental tradition.

Another important arena of cinematic critique in ?O, Zoo! is the film’s use of direct address to set reflexive traps for the spectator. In the next section, the narrator directly addresses the viewer in the imperative:

“There was something peculiar about grandfather’s footage. Watch. Wait for the flash marking the beginning of the shot and then start counting.”

Once again, the direct address underlines the reflexivity of the film by acknowledging our presence as spectators, underscoring its apparent honesty and transparency–even as it more forcefully tells us how to interpret the images (there is something “peculiar” to watch for). But the voice-over tricks us. After the flash, the narrator falls silent for about 20 seconds over a close up of a camel rhythmically chewing. Following the narrator’s orders, we begin to count and fall into sync with the camel’s chewing. But as the shot proceeds, the chewing gets more and more erratic and our counting struggles to keep its own pace. Finally, the voice-over returns to rescue the viewer and explain the “peculiarity”:

“Most of the shots are exactly 28 seconds in length.”

Instructed to count, we are defeated by the rhythm of the image. The narrator’s knowledge further points to our failure:

“I was impressed with both the precision and self-control my grandfather expressed in shooting this unusual material as compared with the erratic camera work displayed in the newsreels.”

“Precision and self-control” are qualities of the text and its “maker,” but not of the viewer. Moreover, the “self-control” is an arbitrary limit set by the apparatus; Hoffman’s camera is a spring-wound Bolex, whose full shot length is 28 seconds at 24 fps.

In addition to direct address, ?O, Zoo!’s voiceover plays with codes of documentary evidence, specifically with one of the most banal elements of the cameraperson’s trade: camera logs. ?O, Zoo! takes this elementary “document” and uses it to critique Grierson’s “technocratic” logic of classification. The narrator suggests:

“More clues as to the nature of my grandfather’s discipline were found on a slip of paper secreted in the film canisters.”

After the shots of the camel, the film cuts to a close up of a piece of paper titled “Camera Negative Report Card,” dated 6/6/45, with neat, legible printing listing six shots, all under the heading “Day 17”: “Lion”; “Elephant slo-mo”; “Fallen Elephant tries to get up”; “Elephant gets up”; “Camel Chewing”; “Insert Humps.” Here is another piece of the film apparatus exposed – and if we read quickly enough, we can see that shot list supports what we’ve been seeing. But questions arise: if this is a slip of paper the contemporary narrator has found, why would it be filmed with the same sepia tone as the grandfather’s footage? The characteristics of different documents (paper and film) begin to collapse into one another.

Later in the film, we see that the contemporary filmmaker also uses these cards to chart the progress of his Holland diary, following in the family line, it seems. But here, too, the very neatness of the “documents” indicates that they are fictional constructions, not a log representing the process of filmmaking but a later construction caught in the false hermetic package of the fiction. All the shots listed on the grandfather’s cards appear in ?O, Zoo! (unless the film has a 1:1 shooting ratio, the report sheets must be reconstructions); both the grandfather’s and the filmmaker’s cards list “S. Mangor” as cameraman (explicable by continuity of family name, but improbable). Finally, later in the diary, we see the right hand part of the grandfather’s card from the first sequence, now dated 6/6/85, as a hand tapes a second card to it and writes “Day 17.” This notation completes, in a sense, the missing left side of the grandfather’s card (also Day 17). It would seem that even off-screen space can be recaptured by the hermetic bounds of the fiction film frame.

Next, the long passage explaining the “making of a short film around the making of a fiction film” establishes ?O, Zoo!’s link to Greenaway and Grierson:

“The footage was found in the winter. That spring, I went to the Netherlands to make a short film around the making of a fiction film. I met the director in a seminar in my native country in the fall before my grandfather’s footage was found. This seminar, an annual tradition since 1939, is devoted to the documentation and categorization of all types of wildlife species ever captured on film. The seminar grew out of the same institution that employed my grandfather as a newsreel cameraman. I can still hear my grandfather’s remarks about the founder of the institution, as he put it, “that old battle-axe.”

This passage appears over shots of animals (a seal, peacocks, an ostrich); images which reinforce the grand father’s employment with the institution dedicated to wildlife photography. The phrase, “documentation and categorization”, alludes to Greenaway’s obsession with classification and naming – that technocratic rage to order laid bare in Greenaway’s films by the hyperbolic application of that rage. Though the allusion is no more than a nod to Greenaway’s project, in recognizing their shared heritage in Grierson, Hoffman acknowledges the ideological implications underlying how documentary convention orders experience – and the subversive nature of any questioning of that ordering.

After the close up of the ostrich and the narrator’s statement, “I can still hear my grandfather’s remarks…”, we cut to a slow motion shot of what seems to be the shadow of two gorillas. The gorilla is a Darwinian “founding father”–and it turns out that the shadows of what appear to be two gorillas are in fact those of a single gorilla and the filmmaker. Once again, in the spirit of Greenaway, Hoffman slyly undercuts claims to cultural authority. On the soundtrack, we hear a mechanical whirring, then an old man’s voice fighting through static and muted sound:

“That old battle-axe! What the hell does he know about this country anyway? All he knows about [sound unclear here] is whoring and crammed up pubs!”

The narrator presents another piece of documentation, apparently a tape recording of the grandfather’s voice (the voice explains the whirring as a tape recorder rewind), literalizing the idiom, “I can still hear him say….” What the narrator hears in his mind can be conjured for the film. The question, “What does he know about this land anyhow?” refers to Grierson’s status as a foreigner to Canada and underlines one of the central ironies of the NFB: an institution designed “to show Canada to Canadians” is founded by a Scotsman. The last line of the “recording” is ambiguous, a false “rough edge” attesting to its status as “document”.

The tape recording introduces a new element into the soundtrack besides the narrator’s voice. The next image, of a gorilla cage next to a spinning water sprinkler, contains a “sync” sound effect of a jet water sprinkler playing underneath the narration:

“Though the director was from the same country as the old battle-axe, I couldn’t see a connection. I couldn’t see why he’d been invited to the seminar. Yet there seemed to be similarities between my grandfather’s footage and the films the director presented at the seminar. I thought I would try to incorporate my grandfather’s footage with the film I would take on location in Holland. As usual, I would keep a diary of the whole affair. [music begins.]”

The “sync” water sprinkler sound (an allusion to another of Greenaway’s obsessions, water), and the introduction of music, fleshes out the possible range of sound at the narrator’s disposal. The gradual and very subtle introduction of each sound option in O, Zoo! parallels the increasingly arbitrary rhetorical power of the narrator and the complexity of the fiction he weaves. The “authenticity” of the “personal” voice-over is first established, and then used as a springboard for the introduction of more and more conventional rhetorical effects. All of this precedes the announcement of the film’s overarching form: “As usual, I would keep a diary of the whole affair”.

Faking Death: the Ethics of Representation, Fiction, and Actuality

This short film around a fiction film has its own enigmas to be worked out in its “narrative” progression. In the passage above, the narrator puzzles over the connections between Greenaway and Grierson, between Greenaway and the Documentary seminar. On one ingenuous level, of course, the puzzlement is justified; Greenaway’s films are, indeed, fictions, and further, are absolutely antipathetic to “Griersonian” documentaries. In specific reference to the 1984 seminar, the “puzzlement” registered by the narrator translated to outrage on the part of many conference participants. The challenge that the anti-documentaries shown at the seminar presented to seminar participants, for whom the Grierson Documentary Seminar was typically a “tribute” to Grierson’sofficial legacy, led to violent debates and charges that films like Greenaway’s The Falls were senseless hoaxes. In ?O, Zoo!, Hoffman seems to be quietly satirizing this debate.

Working out the relations between Greenaway and Grierson is one problem the narrator will tackle. The second is the resemblance he notes between his “grandfather’s footage” and Greenaway’s films. On the level of the fiction, the narrator says he will incorporate his grandfather’s footage into the film he is “about to make” in Holland – the sequence we have worked through is, in a sense, a different film than the ?O, Zoo! to come. On the most banal level, the narrator “discovers” that “the director” shares his grandfather’s fascination with animals. More substantively, Hoffman seems to be announcing that his own exploration of the relations between Grierson and Greenaway will be effected precisely by taking a page from Greenaway’s book. Here, the narrator introduces a hermetic fiction by pretending that his grandfather’s footage is not his own.

These two levels interpenetrate to present two problems: one to the viewer, the problem of reading ?O, Zoo! between the levels of fiction and actuality, between the image and the voice-over. The second problem is Hoffman’s. When he says, “as usual” he would keep a diary of the whole affair, Hoffman is situating the film within his own practice and his own preoccupations – not Greenaway’s assured multiplication and excavation of fictions but his own tentative probings of the problems of representation. The “resolution” of these problems of reading and making appears as the film finally incorporates the two missing shots from the Day 1× shot card: “Elephant tries to get up,” “Elephant gets up.” Just after the diary section shows us the right half of the grandfather’s shot report, the narrator tells a two-minute long story over a black screen, about his witnessing and filming an elephant having a heart attack at the Rotterdam zoo. The passage is descriptive and emotional, centred around the filmmaker’s crisis of conscience in deciding to film the death, and the responsibility and guilt that accompanies it. In the end, he decides “to put the film in the freezer. I decide not to develop it.” At the end of the film, after the credits (in a sense, after the end of the film), two extra shots, both 28 seconds long, sepia-toned, and silent, show an elephant struggling to get up and then an elephant getting up.

The effect of this enclosure of a frame around ?O, Zoo! is double-edged. In one way, these last two shots expose the artifice of the voice-over. The events of the first shot (the elephant rocking back and forth, the attendants shoving bales of hay under the elephant) match the earlier voice-over, but in the second shot, the elephant gets up. The narrator lies twice. First, he developed the footage, and second, the events of the story are contradicted by the image. This decisive break in the fiction takes place by a radical separation of voice-over and image: the story is told over a black screen, the final images are silent. With this separation, the viewer can return to the film to reconstruct, in a sense, its non-meaning, and to question and revise the “authenticity” of the versions of events the film presents.

Working through these possibilities, of course, suggests that a thoroughgoing skepticism is called for in the viewer’s relation to the film, and especially to the narrator’s voice-over. For example, do the final images tell the whole story? Is there more elephant footage than is shown or listed? Is the order of the last two images correct? However, thoroughgoing skepticism is not, it seems to me, the final affect of ?O, Zoo!. It is important to note here a crucial difference between Greenaway and Hoffman: Greenaway’s oeuvre is obsessively interwoven with recurring images, themes, and characters, but his fictions are rigorously hermetic and unconcerned with the codes of realism. In ?O, Zoo!, Hoffman exposes the hoax; moreover, the emotional resonance of the elephant’s struggle is highly charged and excruciating to watch. One suspects that if the story of the elephant’s death is a fiction, it is still a fiction filtered through Hoffman’s sense of the crisis of representation.

The key to Hoffman’s sense of his own intertextuality is the line in the voice-over, “I’ve come across this problem before.” This statement refers to Hoffman’s film made a year earlier, Somewhere Between…. , where Hoffman, travelling by bus in Mexico, comes across a crowd of people around a dead Mexican boy just run over in the road. Hoffman puts away his camera, and cannot film the scene. Somewhere Between… is structured around the absence of the visual representation of the event, which is instead described in written text ‘voice-over.’ Yet, while making ?O, Zoo!, Hoffman did begin to shoot the elephant’s struggle, not knowing if the animal would live or die. The absence structuring Somewhere Between… becomes a kind of contingent presence in ?O, Zoo! Just as Hoffman gathers and organizes the images of Somewhere Between… to hint at, refract, and rehearse the moment of hesitation at the heart of the film, so in ?O, Zoo!, he organizes the film around the potential consequences of his decision to film the event – a kind of rehearsal of the variety of responses he felt as he filmed. The expressive urge behind Hoffman’s work, always constrained by its tentative, questioning attention to and awareness of the process of filming, distills itself into the structure his films adopt: radically extended meditations on a single, almost ecstatic moment.

When Hoffman showed Somewhere Between… at the 1984 Grierson Seminar, he was taken to task by a veteran war corespondent, Don North, who wanted to see the scene of the Mexican boy’s death. Shelley Stamp, reporting on the conference, writes, “[North] felt that the film would have been stronger with the addition of the death. What North missed, I think, was the very structure this absence provided, and Hoffman’s implied critique of North’s type of filmmaking”. The nature of Hoffman’s critique is clearer in ?O, Zoo! In the voice-over story, the narrator rationalizes his decision to film the scene with the lame excuse: “Maybe the television networks would buy the film and tell people the tragedies in their neighborhood”. After the elephant “dies”, he admits, “My idea of selling the film to the network now just seems an embarrassing thought, an irresponsible plan”.

The “social utility” arguments of sensationalist news and documentary makers and institutions always carry a hint of the National Enquirer (“because people want to know”) – an epistephilia which borders on what Tom Gunning has called the spectatorial mode of curiositas (1989:38). But it is important not to see Hoffman’s tentative meditations on the problematic of representation as party to the opposing camp which censors representation under the flag of “responsibility to subject” – the simplistic and squeamish argument that filming “takes advantage” of the subject. Rather, Hoffman understands film’s power to mediate between the consciousness of the filmmaker and the viewer; his hesitations around the problem of representation reflect a personal ambivalence about the necessary link between his vision and the viewer’s. In an “artist’s statement” for the Art Gallery of Ontario, Hoffman writes,

“By means of the personal content of my films I seek to uncover subjective aspects of the way events were recorded. Focusing on the way that I, as a filmmaker, can and do influence both form and content allows room for the viewer to reflect upon ways in which meaning is constructed in film. Using the processes of reflection and revision, I seek to examine and express how we bring meaning to past and present lived experiences.”

If this statement names the terms of Hoffman’s meditation on representation it does not reflect the intensity of the tension felt between the extraordinary control a filmmaker has over images and the guilt they arouse, nor the sense of danger around Hoffman’s approach of the particular “lived experience” at the core of these films, namely, bearing witness to death.

In the voice-over of the elephant story, Hoffman includes a sentence that clarifies this intensity of responsibility and danger:

“concentrating on the image I had filmed as if my mind was the film and the permanent trace of the elephant’s death was projected brightly inside. Somehow it’s my responsibility now.”

Hoffman makes explicit that central insight and concern of radical independent film practice and theory: film’s status as a radical metaphor for consciousness and its relation to the world. The capacity of film to mediate the relation between consciousness (“as if my mind was the film”), and events in the world, centres around its indexical nature (“permanent trace”). This mediation with carries the potential to represent death and suggests a radically powerful level of epistemological inquiry carrying both an intimation of the ecstatic – outside space and time – and what Jean Epstein has called “a warning of something monstrous” at the heart of cinema (1977:21). The “responsibility” Hoffman feels around this encounter with death is keyed by the phrase “projected”. For if film is a radical metaphor for consciousness, we must understand the double-hinged nature of that metaphor as it swings between filmmaker and spectator. Hoffman’s hesitations regarding filming, or developing, or showing his experience of death revolves around a terror of the urgent but reckless energy that representation burns into the filmmaker and the viewer.

If the filming of a moment of death is the central expressive theme of Hoffman’s film, its representation and deferral is never divorced from his recognition that the weight of film history and convention always interposes itself and structures the spectator’s access to the image. The engagement of film history in ?O, Zoo!, especially with the Griersonian documentary tradition with its central claim to absolute truth, underlines the epistemological stakes behind Hoffman’s questioning. Hoffman wants to bring the conventions and history of the construction of certainty to crisis, to clear a space for the spectator to approach, with Hoffman, the intensity of fascination and doubt inscribed in that image which appears literally as supplement, as coda, to the text of the film. The point is not to escape mediation – this is not an Edenic pure image. Nor is it to restore certainty. Rather, Hoffman clears a space for consciousness to reengage the world in “lived experience” via representation.

Works Cited

Allan, Blaine. “It’s Not Finished Yet (Some Notes on Toronto Filmmaking).” Toronto: A Play of History (exhibition catalogue). Toronto: Power Plant, 1987. 83-92.

[Burch, Noël. “Film’s Institutional Mode of Representation and the Soviet Response.” October 11 (Winter 1979): 77-96.]

Della Penna, Paul, and Jim Shedden. ” The Falls .” Cineaction! 9 (July 1987): 20-4.

Elder, Kathryn. “The Legacy of John Grierson.” Journal of Canadian Studies 21.4 (Winter 1986-87): 152-61.

Epstein, Jean. “The Universe Head Over Heels.” Trans. Stuart Liebman. October 3 (Spring 1977): 21-25.

Grierson, John. “The Creative Use of Sound.” Grierson on Documentary. Ed. Forsyth Hardy. London: Faber, 1966. 157-63.

Gunning, Tom. “An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)credulous Spectator.” Art & Text 34 (Spring 1989): 31-45.

Hoffman, Phil. “Artists and their Work: Phil Hoffman.” Pamphlet. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1985.

Morris, Peter. “Rethinking Grierson: The Ideology of John Grierson.” Dialogue: Canadian and Quebec Cinema. Eds. Pierre Verroneau, Michael Dorland, and Seth Feldman. Montreal: Mediatexte/Cinematheque Quebeçoise, 1987. 21-56.

Stamp, Shelley. Program Notes for Somewhere Between… . pamphlet. Toronto: Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, 1984.

Winston, Brian. Claiming the Real: The Documentary Film Revisited. London: BFI, 1995.

* “In one delicious sequence, Hoffman ironizes Greenaway’s move to big budget feature filmmaking. While Greenaway’s crew makes futile attempts to corral a flock of flamingos, Hoffman simply sets up a feed bucket in front of his Bolex. A flamingo approaches and he gets the shot; personal control of the apparatus has its rewards.”

** “My thanks to Karyn Sandlos for her excellent editorial work on this essay

Somewhere Between interview with Philip Hoffman (by Donnalee Downe 1984)

by Donnalee Downe

23 November 1984

DD: Can you tell me a bit about how you went about shooting and editing Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion?

PH: I had been reading some Haiku poetry at the time. Haiku is a Japanese form of poetry which is very simple, yet complex in its simplicity. In fact, when I went down to Colorado that was a poetry convention of sorts. So I decided what I wanted to do in Mexico was shoot in a similar fashion, borrowing from the form of Haiku poetry. I tried to think of the Bolex camera’s twenty-eight second wind as a structure rather than a limitation. Most of the shots in the film are twenty-eight second takes: the “breath” of the Bolex camera.

I tried to make each shot sparse in its content: the coke sign, the donkey, the open road, the mother and child running, (c) simple, uncomplicated shots. In shooting The Road Ended at the Beach, I had a lot of expectations… about “the big trip”. I felt I had to make the film, it was my first since school. There was a lot of pressure and tension and not much fun. So it was important with Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion to shoot when I felt like shooting so it would be more like writing poetry.

DD: But it wasn’t until you returned that you decided it would revolve around an image you didn’t have.

PH: Right. So in a way it was a lot of little poems. On the trip I kept a journal and I tried to write little phrases based on the haiku form. Not that it was at all like traditional haiku. I tried to develop a style, to let a form develop out of an idea. When I came back from the trip I didn’t know what the film would be about. I hadn’t shot that much film—about seventeen minutes—and the film is only six minutes long, so it was pretty economical. When I came back, the experience on the bus was still on my mind. I didn’t have the footage and didn’t regret not having it, it was something I just didn’t want to do at the time. I remember putting the camera down and thinking no, I don’t want to do this.

DD: The sparse images you described facilitate open interpretation. The emptiness opens to the missing image.

PH: They’re open but there are still some things that were on my mind while shooting. I kept going back to the churches.

DD: Are the religious images linked to the boy’s death?

PH: No, they’re a reflection on my own experience as a Catholic. Religion is most visual in Mexico. I was interested in icons and in the beat people—beatific in the Kerouac sense—sympathy to humanity. I see more spirit in the people than in the icons, let’s put it that way.

DD: How do icons function in the film? We talked earlier about film language. The meaning of the images is largely defined through the film itself through their relation to the death, and yet the icons have such strong connotations.

PH: Yes you can interpret an icon in many ways. For me it was a way of working through Catholicism. You’ll see more of it in my next film.

DD: Did you decide to tone the black and white footage to facilitate a less dramatic contrast with the colour footage?

PH: From a formal standpoint it helps blend the high-contrast shots with the colour. I also wanted it to look old—but not the way we are used to seeing representations of the past in film. Hollywood uses sepia. My first text states “looking through the lens/ at passing events,/ I recall what once was/ and consider what might be.” The first shot is of a black band. We hear the music of a saxophone and see a trumpet. There’s a sort of visual/aural pun there. We’re used to sync sound, but in the last line of the preceding text it’s clear that, well, with film we can do whatever we want.

DD: In the text you changed tenses. For example in the third text: “The white sheet is pulled over the dead boy’s body/ the children wept.” It’s almost like looking at someone’s memory. The temporal connections are unclear but we’re content with ambiguity.

PH: I believe in an open form where you’re not told what to think. I suppose it is a metaphor for memory. I honestly didn’t think about the different tenses in the text, I went with what sounded good to my ear. It jumps around and that’s in keeping with putting myself in the past while making, finding myself on the bus again, while I’m really at home in my Bathurst Street basement.

DD: The shot with the Coke sign and the donkey cart has temporal ambiguity too. The sign is obviously modern and the cart so primitive.

PH: Again, there are many ways this can be taken and the ambiguity is important. For example, the last text: “big trucks spit black smoke/ clouds hung/ the boy’s spirit left through its blue.” What is that blue? Is it blue smoke from the trucks? The blue of the brick wall?

DD: It brought me back to the wall.

PH: It did? That’s one of the things I liked about the line. It is ambiguous and I don’t profess to have an answer. To end on a line like this ” the boy’s spirit left through the blue” it’s almost like a traditional religious experience. I suppose this brings us back to my Catholic history and the icons in the film. The line is directly from the journal and was written on the bus. I suppose it was the blue sky that I saw at the time.

DD: I’m comfortable with ambiguity. I guess it’s partly because the second text tells me that there’s no footage of the central image. I don’t have expectations. I don’t wonder how the boy died.

PH: It was the second death I’d seen on the trip. The first was a terrible car accident in Colorado. I didn’t film that either. The windshield was the movie screen and the camera was right there, but no way.

DD: Do you remember deciding not to film the Mexican boy?

PH: I remember my hand on the camera and it would have just been a matter of leaning out. I guess all the media footage we see every day flashed through my head.

DD: I think the absence of the footage is more striking. We’re saturated with media-like images.

PH: Well, the media images are striking, but I think in this case actual footage wouldn’t leave any room for analysis of death and our feeling towards it. Media images are too overpowering. That’s why I put the camera down. I think it’s more successful as a meditation in its absence. There is another text which I think is awkward, yet perhaps one of the most important: “I should have a bible,/ you suppose I lent it to someone/or someone stole it.” Most people ask, “Is that poetry?” It brings us back to the first person that’s having this experience. For me, it symbolizes a loss of religious faith in the Word, in the icon, in what we’re taught in religious classes. Today the Bible seems irrelevant. People take whatever meaning they want and use it for their own cause… and yet the Bible (like the film) is an open form. Its ambiguity facilitates many interpretations.

DD: I guess it’s a question of how didactic one is about a particular interpretation.

PH: Perhaps that’s how it should be read. Let people read it and take out of it what relates to their experience… rather than Jim Baker and the P.T.L. Club saying what it means.

DD: For me, the music really helps define my proximity to the central image. When the tempo is upbeat, in the shots of the two bands for example, the boy is almost forgotten. When the music slows I feel closer to the tragic event. Can you explain how you and the musician decided upon the music?

PH: I showed Mike the film and we worked on it together. I left the film with him and he worked with it and soon certain riffs started to develop, and then it was just a matter of getting it right. We did six takes and I edited the first version which I wasn’t really happy with. Because it was edited it didn’t seem continuous, it didn’t seem to flow, so we tried again. This recording went directly to 16mm magnetic tape. There were things that he did that, if he was three frames off, it would change the mood completely. We did seven new takes and finally we felt we had it. We were both really tired but decided to try one more and we got it. Only one section was edited, I took that whole section from the sixth take. I think it’s hard to write the music down, it’s certainly possible but perhaps it’s not as direct. I like to work in a way so that everything comes out of experience.

DD: The diarist of The Road Ended at the Beach expresses frustration and disappointment at the failure of events to live up to expectation. One has a strong sense that the camera comes between you and your fellow travelers, thatit distorts what you want to record.

PH: At one point in this film I state: “The best time for me is when I’m on my own with the camera.” Later there’s another reference to how the camera gets in the way. At this point the spectator realizes that the camera is part of the event. In the first part of the film we are painting the van, it’s very mysterious. The guys are preparing for the trip west. It’s very linear at first, setting up the form. I suppose one of the first references to the camera is in a shot in the cabin. Rub Chan asks me if I want some whisky and starts to get up. Richard says, “No, No, No, don’t get up.” And I get out from behind the camera. It’s the first filmic reference to the camera. There are a lot of problems with directly autobiographical films. It seems that when a film is too direct, too personal, you meet a lot of obstacles. I tried to use my personal experiences as a vehicle for something more universal. In Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion the universal experience is death. It’s an analysis, not just of personal experience, but of how this experience is incorporated in a much larger context.

The Value of the Parochial: Film and the Commonplace

(an excerpt from a larger article publication forthcoming)

by Janine Marchessault

I was still a young boy when I saw my first film. The impression it made upon me must have been intoxicating, for I there and then determined to commit my experience to writing…. I immediately put on a shred of paper, Film as the Discoverer of the Marvels of Everyday Life, the title read. And I remember, as if it were today the marvels themselves. What thrilled me so deeply was an ordinary suburban street, filled with lights and shadows, which transfigured it. Several trees stood about, and there was in the foreground a puddle reflecting invisible house façades and a piece of the sky. Then a breeze moved the shadows, and the façades with sky below began to waver. The trembling upper world in the dirty puddle—this image has never left me.

— Siegfried Kracauer (Ii, 1960)

We can see the development of strategies based on coincidence, accidents, indeterminacy, endlessness, and contingency in documentary and experimental filmmaking of the post war period expressly in this light. As a means to work through some of Kracauer’s insights around cinema and the “whole world”, let me turn to a specific work—the short ‘travel’ film Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) by Canadian filmmaker Philip Hoffman. The film was shot under the influence of Jack Kerouac and inspired by the Beat Generation. Kerouac went on the road in the fifties to wander and to have experiences, to create a scene across cities, New York, San Francisco and Mexico. ‘On the road’ refers specifically to a mode of writing that is quite literally writing while en route. It is after The Town and the City and through On the Road that Kerouac developed his art of ‘spontaneous prose’, an improvisational method of writing in time connected to the flow of life like jazz. Famously he used a full roll of Teletype paper that matched the road and typed the novel almost continuously over three weeks. The roll enabled him to write without stopping, without interrupting the flow of words, essentially mirroring the experience of driving. Kerouac like Gertrude Stein before him, associates writing with a phenomenology of the mind, a writing that is “composed on the tongue rather than paper” (Ginsberg 74). Kerouac’s writing does not seek to transcend mediation so much as it does to document its actions so that writing becomes a record of the connection between inner and outer structures of perception, binding bodies to places through time. As much as it pushes the boundaries of presentness, writing like film, is always in the past. Although the fact of mediation between word and image is altogether different as Kracauer would stress.

Hoffman made Somewhere Between, after attending a conference devoted to the legacy of On the Road in Boulder, Colorado. Yet Hoffman’s film is not so much on the road (the highway) as it is on the street, featuring two cities (Boulder and Toronto) and towns somewhere between the cities of Guadalajara and León. The film cuts across various scenes in these places with lengthy (often twenty-eight seconds) unedited sequences of action and black leader as “measured pauses” (Kerouac’s silence or breath) between sequences. These juxtaposed moments play out a reflexive rhythm that foreground the randomness and stubborn indeterminacy of the images of everyday life, and of their placement in the film. We are presented with situations that are delimited without being explicated. The film opens with a text on the screen: “Looking through the lens/ at passing events/I recall what once was /and consider what might be.” Two early sequences in the film give image to these words. The first is an image of what is now a cliché of globalization. The static camera poised on a street corner in the centre of a small town in Mexico, frames in long shot, a mule and buggy parked beneath a large red Coca-Cola sign, a tangle of telephone wires above low rise dilapidated buildings. The only movement in the frame is the cars, driving in and out of it, and a woman and child crossing the street. Yet movement and layers of interaction are implicit in the juxtaposition of the mule and the global corporation, which co-exist in this place. This image is preceded by another static shot of a church down the street, doubly framed between two pillars of a Catholic arch. Looking in, the camera reveals someone deep in prayer. After a motionless few seconds, a child interrupts the stillness of the sequence, enters the frame and begins a game of crawling up and down on chairs. The child’s sudden appearance is precisely that kind of “unexpected incident” that Kracauer delights in—“the stirring” of nature and people that the Lumiére films first captured. The kind of “spontaneous writing” that we often find in experimental ethnographies favors a self-reflexive methodology[1]. In this instance, focusing on the physicality of the scene to include the temporal structure imposed by the camera (i.e., the spring wound Bolex’s 28 second take) and the filmmaker. The acts of “looking through the lens” as Hoffman’s text tells us, calls upon a time-based aesthetic where past and future co-exist beyond the edges of the frame. Yet it is not only the film strip/ flow of life analogy that foregrounds this temporality. It is also the reoccurring themes of religion and children, of tradition and horizons that Hoffman finds across the different places in the film. Given that the film concerns the story of a Mexican boy run over by a truck somewhere in Mexico, these themes resonate throughout. The boy’s death is an event that the filmmaker refuses to film (or include in the film) but instead conveys through a poetic text on the screen that is intercut throughout the film. Filled with black holes overwritten with the poem that remembers the boy’s death, the film’s architectonics are structured by the words that never conflate the commonalities between the situations. The poem embeds the boy’s death in all of the images of the film so that it is not inconsequential to the corporate sign, the superstructure in the opening images but rather stands in a contiguous relationship to it as to all the images in the film. The melancholic saxophone that draws the line from Mexico to Colorado to Toronto, seems to synchronize momentarily with the musicians and children holding out cups to collect money in these different places but then separates and floats over them from an off screen space that leaves the frame open to a multiplicity of found stories: children playing games on different streets in different cities, a crowd kneeling outside a church, the Feast of Fatima procession in a Portuguese neighborhood in Toronto, little girls dressed as angels and streets lined with telephone poles, the beautiful patina of pealing walls aged by the weather, graffiti palimpsests in different languages, a paint brush sketching a likeness of Jesus from a painting of Jesus, a child crawling up and down on a large sculpture of a sea shell in an outdoor street mall, a pond surrounded by trees at dusk. The camera stages situations from a distance and in long shot; sometimes the movements of bodies are slowed. But it is the materiality of the built environment that is framed to equalize the human and the non-human (trees, benches, windows, sidewalks, statues, cars, signs) which are counter influencing and interpenetrating processes. We see here the manifestations global cultures, national and urban idioms and technologies that the film stages as commonplace.

In the study of localities, filmmaker and anthropologist David MacDougal points out that it is not singularities but interconnectivities and flows between particular cultures that lead to the cinema’s capacity for deeply phenomenological and pedagogical gestures. Somewhere Between gives us the interval or the interface between places where identities and experiences take up their meanings in Hoffman’s memories of a shared world. Yet it is also the characteristic of the “found story” that it remains open, fragmented, that it burn through myths and clichés. It must resist the “self-contained whole” that would betray its force by casting a tight structure with a beginning, middle and end around its anonymous core. The found story Kracauer explains arises out of and dissolves into the material environment, often in “embryonic” forms that reveal patterns of collectivity (Theory 246). The found story comes from the aesthetic of the street and we should add, holds infinite possibilities for the psychic investment in the whole even as it takes it apart. In the end, Hoffman may well have broken with Kracauer’s prescriptive visual aesthetics by staging reality with word, image and black leader in a way that actively petitions the dreamer to envision what was and what might be. What holds the spectator’s interest in Hoffman’s film is the gap, the place of imagining: the black smoke from the truck, the children weeping, the sky and the boy’s spirit as it “left through its blue”.

[1] Take for example the films of Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Jean Rouch, Agnes Varda or Chris Marker who use the camera as an intrinsic aspect of performance. We could also include some of the more self-reflexive documentaries by the Unit B directors at the NFB of Canada. Cf. Catherine Russell Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video (1999).

Read whole article here

Avant Ghosts of Mexico

by Jeremy Rigsby

Travelogues are films made by tourists. They are defined by their creators’ decision to remain on unfamiliar terms with unfamiliar surroundings. These are not documentaries, which presume or strive for some unmediated relation to their subjects. Unless they can demonstrate that they are provisional and selective, documentaries are prone to be mistaken for the truth. Unless they can demonstrate that they are art, travelogues are largely the product of hobbyists who can afford vacations. Travelogues may affirm their artfulness by appealing to an aesthetic derived from the lyrical avant-garde, or, more frequently, by adopting the discursive strategies of fiction films. Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion takes the latter route, all the way to a Mexican crossroads of the Real and the Imaginary.

The fictive convention relied upon by Somewhere Between establishes an artificial contiguity between the film’s two discrete components: intertitles alternating with images (of Mexico, mostly). This convention is associative editing, a neat version of the so-called Kuleshov effect, whereby details noted in the intertitles are presumed to refer to the images they immediately follow or anticipate by the simple virtue of proximity. The dead youth is nowhere seen or implied in any of the footage. The titles state that Hoffman “put the camera down.” But the cop car that sped by his corpse must be the very one just seen passing the Coke billboard. Likewise the beggar girl who was conceded a peso is identified as the beggar girl who then appears. And the girl with the big eyes awaiting her dead brother? There she is, her imputed lingering iterated by symbolic association with a concrete snail. Much of the film’s remaining footage is neutral and irrelevant to the text, but marshaled to support a funereal aura through melancholy slow motion or sepulchral, greenish-black tints.

That the film’s apparent coherence of text and image is a construction of cinematic artifice should be obvious, but the film condescends to underline the point. The soundtrack, a plaintive sax solo, twice jars incongruously with footage of musicians playing visibly different tunes, prompting suspicion of any facile congruence between events and their remains in the picture world. And in a sequence quite exceeding the credulity that associative editing might sustain, a funeral procession plods down conspicuously non-Mexican (i.e. Toronto’s) streets, a near-parodic intrusion that must be rationalized as a metaphorical digression on the universality of death, or some such thing. All these contrivances and retractions cumulate in a film whose reliability as documentation is severely undermined by its imperative to simulate fiction. Somewhere Between thus exploits a special tension inherent to the travelogue as a genre. Conventions that would affirm the continuity of narrative films, or the veracity of documentaries, are here destabilized, indeterminate, somewhere between… where, exactly?

Clearly not the poles of a debate concerning the film’s ethics, which it suffered when it was first exhibited in 1984. Its supporters regarded the omission of the child’s death as a noble refusal of spectacular and exploitative documentary practices. Its detractors, conventional ‘journalistic’ documentarians, considered the film irredeemably deprived of the potential impact conferred by such a powerful image.

Both these arguments assume the film’s images support the text, signifying only the conclusive absence it describes. But the latter position does implicitly contain a more incisive interpretation: footage of the accident or its aftermath would confirm that it actually happened. This shopworn raison d’etre of the journalistic documentary finds application here; an appeal to evidence validates the skepticism this film seems designed to provoke. Its issues aren’t ethical but ontological. Did the dead youth exist, or did Hoffman invent him? Given the film’s lack of positive evidence, coupled with its protracted insistence that it be acknowledged as a synthetic construction, the question remains. There are two plausible answers. In the first instance, Hoffman sifts through a large amount of Mexican vacation footage to find a few shots that, by chance, contain imagery similar to details he recalled of the accident and to the text he wrote to describe it. Or he returned from Mexico with a relatively small amount of attractive but disparate, mismatched footage which he united into coherent form by fabricating the accident as a kind of plot device.

Occam’s razor might suggest the second option, but that’s not the rub. As film critic Rita Gonzàlez writes “…international filmmakers have been drawn to the notion of Mexico as a transgressive or mythic space, an eidolon that they have done their part to perpetuate.” [1] As the avant-garde film canon attests, south-of-the border has been a popular destination for filmmaking tourists, the special condition of their alienation in Mexico circumscribed by this imperative to solicit visionary experience. The roster of sojourners include Bruce Baillie, Bruce Conner, Richard Myers and Chick Strand, who made most of her career around Guadalajara and once confidently decared “Mexico is surrealism.” The Mexican travelogue is almost always their projected phantasmata. The ‘reality’ of the death in Somewhere Between is akin to the ‘reality’ of, say, the quintessentially Mexican peyote hallucinations in Larry Jordan’s Triptych In Four Parts: that is, as real as permitted by illusory circumstances. The virtue of Somewhere Between is to be conscious of its complicity in this tradition of cultural mystification. It inspires and permits doubt. It doubts the authenticity of the particular experience it describes, the authenticity of Mexico as an experience of the ‘mythic,’ perhaps ultimately even the authenticity of experience in general. Typical of the traveler’s tale is a tendency to embellish. Rarely is it so evocative, or so obliging, of the tendency to disbelieve its teller.

- In ‘The MexperimentalCinema,” catalogue essay published by the Guggenheim Museum, 1999.

Letter from Peter Greenaway

Peter Greenaway

28 St Peter’s Grove

London W6

January 24th 1984

Monique Belanger

Arts Awards Service

Canada Council, Ottawa

Dear Ms Belanger,

I met Phil Hoffman at the 1984 Grierson Seminar. His films were a breath of fresh air amidst so much conventional material. His films blithely side-stepped the orthodoxies so taken for granted by those who believe documentary cinema is an educational rostrum, is about questions of balance, is essentially a dissertation on something described as ‘truth.’ Meeting him in the context of his films backed up my impressions of his aims and abilities. His work is an encouragement to those who want to use autobiography as subject matter, personal vision as a trademark, and show how small resources can be a positive virtue.

It was Phil’s suggestion in London several months later that he would like to be some sort of witness to the feature production of the film Zed and Two Noughts in Rotterdam in the Spring of this year—which I am certainly agreeable to—though I will not hide the fact that I believe, as a filmmaker with a personal vision, he is well past the apprenticeship stage. What he needs now is opportunities, encouragement and experience. Since his method is to work with a camera as a constant companion, I would wish he could be encouraged to make a modest film whilst he is in Rotterdam and London, certainly to be encouraged to shoot some two or three thousand feet of 16mm. The desirability of his presenting a script before hand, as far as I can see, is not necessary, considering his work method. In fact, I think it ought to be a condition of his association with the Zed and Two Noughts project that he shoot on his own on any subject whatsoever.

Most of the relevant detail of the production of Zed and Two Noughts Phil has already mentioned. It is perhaps not so strange a co-production, as seen from a British point of view, but nonetheless will present a nicely complex mixture of finance, production, cast and crew that aptly mirrors the complexity of the film’s structure and content—the ambivalent diversity of species and purpose—of beasts and men—both sides of the cages in a zoo. Phil has volunteered not just to stand by and observe but to offer practical help which will always be useful on such a modestly budgeted, ambitious film.

If he (and you) believe that he (and you) can profit by his experience with the production, then I am certainly happy to invite him. If there is anything else you would like to know, I am sure I can help, though I would be obliged, as I am sure you would understand, to keep bureaucracy to a minimum. The production of a feature film is very time-consuming and demanding.

Here’s hoping that you can agree to Phil’s participation.

Yours sincerely,

Peter Greenaway

The Road Ended at the Beach

16mm, 30 minutes, color

by Philip Hoffman

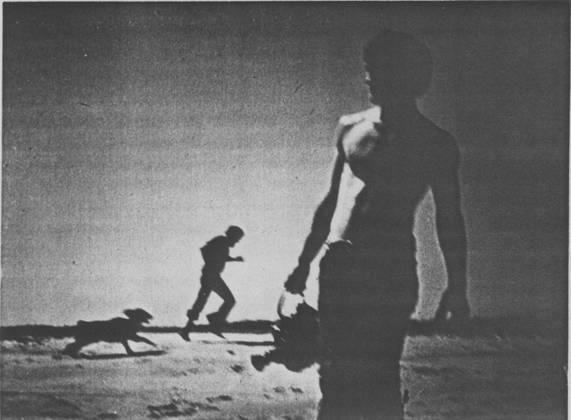

The film is a series of “telling” incidents in which events, which fall short of expectations, are confronted by more “vibrant” memories of the past. The subject, the filmmaker/diarist, whose consciousness encompasses this flow or passage of time, uses failure to make his strongest points about the convergence and intermingling of anticipation and event, experience and memory. On the road, he and his friends spend time with an old buddy who makes his own music at home but has to play in a military band to earn a living, forcing them to come to terms with their own diminished expectations on the trip they are undertaking as compared to trips in the past. The story of a wood carver who lives with his family in rural Nova Scotia seems idyllic until we find that he must also work in a fish cannery to survive. The film itself is an account of failure. Spurred on by the mythology of Jack Kerouac and his life on the road, the travellers visit Robert Frank in order to learn first-hand about the Beats. Frank matter of factly dismisses their quest by noting that Kerouac is dead and the Beat era is over. In a partial response to this shattering of the myth, the filmmaker goes back over the ground of the journey once again, only this time he includes the frustrations, the dead-ends and the low spots. The smooth, linearly developing narrative that we earlier understood to be the product of the filmmakers consciousness is now questioned and replaced by a series of stops and starts, memories and reveries. The final sequence of the film marks a re–evaluation and change most emphatically. The sequence shows a beach in Newfoundland on a bright clear day; children and dogs crossing in front of the camera. Yet each time someone disappears off-frame the filmmaker jump-cuts to a new action. On the beach where the road ends discontinuity becomes a virtue, a form of concentration that validates exceptional experience, just as recollection and anticipation validate certain memories and fantasies.

– David Poole 1984