16mm, 30 minutes, color

by Philip Hoffman

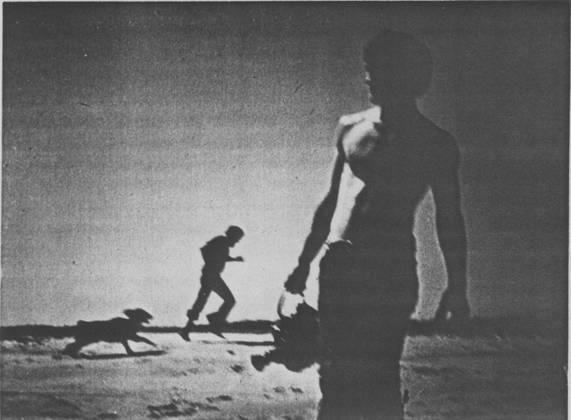

The film is a series of “telling” incidents in which events, which fall short of expectations, are confronted by more “vibrant” memories of the past. The subject, the filmmaker/diarist, whose consciousness encompasses this flow or passage of time, uses failure to make his strongest points about the convergence and intermingling of anticipation and event, experience and memory. On the road, he and his friends spend time with an old buddy who makes his own music at home but has to play in a military band to earn a living, forcing them to come to terms with their own diminished expectations on the trip they are undertaking as compared to trips in the past. The story of a wood carver who lives with his family in rural Nova Scotia seems idyllic until we find that he must also work in a fish cannery to survive. The film itself is an account of failure. Spurred on by the mythology of Jack Kerouac and his life on the road, the travellers visit Robert Frank in order to learn first-hand about the Beats. Frank matter of factly dismisses their quest by noting that Kerouac is dead and the Beat era is over. In a partial response to this shattering of the myth, the filmmaker goes back over the ground of the journey once again, only this time he includes the frustrations, the dead-ends and the low spots. The smooth, linearly developing narrative that we earlier understood to be the product of the filmmakers consciousness is now questioned and replaced by a series of stops and starts, memories and reveries. The final sequence of the film marks a re–evaluation and change most emphatically. The sequence shows a beach in Newfoundland on a bright clear day; children and dogs crossing in front of the camera. Yet each time someone disappears off-frame the filmmaker jump-cuts to a new action. On the beach where the road ends discontinuity becomes a virtue, a form of concentration that validates exceptional experience, just as recollection and anticipation validate certain memories and fantasies.

– David Poole 1984