“Over the last thirty years, Phil Hoffman has often been called Canada’s pre-eminent diary filmmaker. The release of his first feature film, All Fall Down (2009) offers one an opportune chance to reconsider his body of work, his diaristic practice and its relationship to documentary. Revisiting Hoffman’s diverse oeuvre is a revelation: it quickly becomes apparent that Hoffman is one of Canada’s most important documentary filmmakers, full stop. To make this case, one only needs to look at the current ubiquity of ‘hybrid documentaries’ and the critical and ethical debates surrounding their emergence. The term itself is of recent provenance, yet Hoffman has been making what would now be considered ‘hybrid’ documentaries since his first film in 1978, On the Pond.” by Scott MacKenzie – POV magazine, Issue #76 Download as PDF

Category Archives: Reviews & Articles

Shot of Solitude: Hand (and Heart) Processing at the Film Farm

By Ken Paul Rosenthal

from http://www.incite-online.net/rosenthal.html

I am flying on Air Canada to Phil Hoffman’s Independent Imaging/Filmmaking Retreat on a farm northwest of Toronto, where I will shoot and process motion pictures, learn tinting and toning, and view contemporary experimental films. It’s been 11 years since I was introduced to the tactile universe of hand processing movie film at the San Francisco Art Institute. Watching the beautiful mess of images emerge from a stainless steel womb for the first time entirely changed the way I make films.

Hand processing is a practice where serendipity is the rule rather than the exception; an antidote to conventional methods of filmmaking that emphasize image control. Whereas new technologies moved me away from the medium, I could use my own hands to embrace the film material more directly and intimately. Over the years I have hand-processed hundreds of rolls of film and shared my experiences in dozens of workshops. Now I’d have an opportunity to learn recipes and techniques from other passionate practitioners and work in 16mm for the first time.

The stewardess offers me headphones for the onboard movie, but I decline and turn my attention instead to the film unraveling outside the cabin window. The sifting contours of the clouds remind me how much hand-processing movie film is like playing in a celluloid sandbox. It can also be quite terrifying. You discover your heart isn’t as malleable as the medium, and you start scraping away at it until only the most precious cell is left. That frame, that naked grain, is your silver soul.

Mount Forest, Canada

I am standing alone in an open barn door. In front of me a tree traces the grass with tender brushstrokes. I turn and enter the barn, where pillars of light ring the space like a motionless zoetrope. It is the morning after the retreat has ended, and I’m still nursing my last shot of solitude.

Although the 11 other participants have departed, the after-effects of five days of nonstop filmmaking are evident everywhere. Glistening strips of hand-processed film drip-dry and flutter from a 15-foot clothesline inside the barn. My own footage wraps around the line in impossible tangles. Short, crazy-colored pieces of film swim in bowls of toning solution. Half-eaten bits are stuck to the fridge like a proud child’s schoolwork. Sheets of opaque plastic cordon off the darkrooms. Just yesterday those same plastic curtains barely dampened the giddiness of fellow processors, who emerged from the darkrooms like proud parents, shouting, “Oh my God, look at this!” as people scurried over to see their newborn images, launching into a chorus of “Oohs,” “Ahhs” and “Wowwws.”

The film retreat was a carnival of creativity, and the barn was the funhouse. At least it was for most of the participants. Looking back, I can’t help but wonder; what was I doing in the farmhouse cellar futzing with my Bolex’s rex-o-fader for two hours while the resident sparrows were pooping on my head? How did I expose an entire day’s shoot to a 100-watt light bulb before it hit the first developer? And why the hell did I go ahead and process it anyway?! Instead of producing images, I made a series of increasingly catastrophic mistakes. Why was it so difficult to practice what I’d long been preaching to my hand-processing students: dissolve prescribed ideas and embrace the process from which the most elegant visions arise?

When I arrived six days earlier, I was prepared to make a dance film. That ambition quickly dissolved when I took on a Bolex Rex-4 as my shooting partner. Having only shot with highly mobile Super-8 cameras for the past 15 years, I found the 16mm Bolex a beast to handle. Using a Sekonic meter to read the light, stopping down the aperture and then recompose before shooting didn’t feel spontaneous. Instead of embracing the Bolex’s noble weight and its economy of functions, I kept wrestling with it. The camera didn’t fight back, it just sort of went away, piece by piece.

Over the next two days I lost the backwind key, a 24-inch cable release, and the filter slide (thus fogging an entire day’s shoot). I also stripped the threading in the crankshaft. With each additional piece of equipment lost or broken, I was forced to peel back another layer of intention. I let go my idea of making a dance film, and I let go my desire to leave the farm with a finished film. After all, I was always reminding my students that film is less about making a film than it is about experiencing the making. And that the texture of the gesture becomes the film. Now I needed to take my own advice.

However, abandoning the images and ideas I had developed in my mind filled me with despair. Without a script or a preconceived vision to guide me, I felt crippled and blind. I did not know which side of the camera to place my attention on, and collapsed to the ground. It was at that moment that an image came to me—my hand reaching through the lens and fondling the sun. I thought about my little focus-free 35mm still camera (which had slipped out of my pocket into a bucket of water that morning) and how liberating it felt to point it and just shoot whatever I found beautiful.

I stood up and immediately began filming in the same way I had made still pictures, without any camera movement, simply framing my subjects for their texture and the way they embodied the light. I shot burlap riding the wind. I shot barbed wire choking wild straw. I shot a newborn calf’s placenta until an irate bull chased me headlong through the electric sting of a charged fence. As the Bolex and I moved arm in crank through pastures and forests, I realized I was making a dance film after all. Only the dance wasn’t taking place in front of the lens, but in the space between the camera body and my own. And I realized that my struggles had not been about making mistakes or knowing what to shoot, but about how to compose my self. I had taken a shot of my solitude, and it was a good fix.

Everyone’s activity reached a fever pitch on the fifth and final day in preparation for our evening screening. Filmmakers darted from pasture to darkroom to flatbed in frenetic circles, with pit stops at the tinting table, optical printer or homemade animation stand. The resident Steenbeck had a wonderful malfunction, which caused the plates to clang like a locomotive pulling into a station, or dinner bell calling everyone to our celluloid feast.

An hour before showtime I chose my selects, drew up a paper edit and assembled a rough-cut. As I hastily sifted through reel after reel of misfortune, a few silver jewels began to emerge. After my piece screened, a warm shivering welled up in my chest as I shared the details of my innumerable mishaps. Although everyone applauded my work’s photography, the images of my solemn, distended shadow hugging an endless road, of rotting barn shingles and a lonely leaf framed against a setting ball of sun were documents of my solitude.

Now it’s the morning after the retreat has ended, and I am standing alone in the barn wondering what to do with my film, with myself. Should I return to the fields and re-shoot all my mistakes? Should I bury my film in front of the barn, where exhausted chemistry had spilled? Or should I just chuck the whole mess into a vat of blue toner? The answer gently materializes when I stop asking questions: continue filming what I find beautiful—the film material and the process of making film. I shoot film images rising out of a chemical bath, film stock spilling into a discarded porcelain sink, film strewn across a long row of bushes and negative film reversing to positive under a light bulb.

With only two hours before my departure, I find the courage to pull off my fantasy shot with the help of Christine Harrison, one of the retreat assistants. We leave the farm and head toward an enormous field of daisies, where I plan to have Christine film me prancing naked in slow motion with an armload of film. We arrive and knock on the door of a private residence neighboring the field to ask permission, but no one answers, so we get right to it. I strip down, then leap and roll about, trampling daisies with blissful abandon. Each time a car approaches on the road, I duck down into my robe of blossoms. As a comic counterpoint, I decide to stand center-frame with a ball of film covering my genitals while I peer about timidly. We are setting up the shot when Christine alerts me to an approaching truck. I figure an 18-wheeler will consider my daisy cheeks worth no more than a toot of his horn. Instead he slams on the brakes and screams bloody murder. This draws out the woman from the nearby residence, whom we thought wasn’t at home. She begins to scream about there being children in the house and threatens to call the police. (Could it be they don’t appreciate dance?)

We gather up clothing and equipment in such haste that my eyeglasses are left behind. So we dash back to retrieve them, but find nothing among the yards of smashed blossoms. Christine seems particularly unnerved. I’m not sure if it’s because the authorities might confiscate our equipment, or because the reputation of the film camp would be irreparably damaged. Regardless, she promises to return that night to search some more, and I drive off to Toronto with the entire world looking like a four-laned fishbowl.

So went my experience on the film farm. I danced with my dark side, my light side and all the other gradations of my silver soul. I lost my eyesight in one sense and gained insight in another, as corny as that sounds. I know deeply and intimately that film is (for me) fundamentally not about recording a picture. It is a process even broader than the developing of images. It is about dancing with stillness and manipulating a novel posture for my heart. Phil Hoffman, the compassionate angel who manages the farm, says that film is about the moment of transformation, and that making love for your self is a reason to make film. Words to shoot by indeed.

I have yet to process the film I shot on my last day at the farm, but that’s OK. I only exposed it as a means to a beginning.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ken Paul Rosenthal is an independent filmmaker, teacher and activist. His films weave personal and political narratives into natural and urban landscapes. Rosenthal is the recipient of a SAMSHA Voice Award for his media work in mental health advocacy, and a Kodak Award for Cinematography He holds an MA in Creative & Interdisciplinary Arts, and an MFA in Cinema Production.

Film–Is There a Future in Our Past?

(The Afterlife of Latent Images)

By Rick Hancox

INCITE

Is film dead, or are rumours of its death–as in Mark Twain’s response to the gaffe about his own demise–“greatly exaggerated”? Rumours of film kicking the bucket are nothing new – “FILM IS DEAD” was a banner headline in Daily Variety in 1956 when videotape was invented. Maybe I should have called this talk “A Fleeting Filibuster on the Future of Film,” but it seemed that a title relating to the past was appropriate, thus “Film – Is There a Future in Our Past? (The Afterlife of Latent Images).” The idea of the latent image–exposed film waiting for development–is one of the key differences between film, and its bond with the past, and video, with its virtual window on the present. Of course once the latent image is developed, and comes to life on the screen, it only knows the present tense. Thus, the notion that film’s future as a medium is in its past, is one of the ironies I want to explore.

Read the rest of the article here.

Notes on river

by Philip Hoffman

The Saugeen River was named Sauking, ‘where it all flows out,’ by the Ojibways in the early 1800s. It runs into Lake Huron. The place where I know it is twenty miles south of Owen Sound, Ontario, near Williamsburg, where I spent lots of time in my youth exploring. Over the past dozen years I’ve returned there to film. In 1977 with a wind-up Bolex and one roll of 16mm color film. In 1981 with a 1/2″ reel to reel, black and white video portapak. In 1984, indoors now, with a rear screen set up to record on video the original 16mm footage. And then again in 1989, the camera went for the first time beneath the surface in an underwater housing, the camera loaded with high contrast printer stock.

All the video images were transferred to film in the version that’s now in distribution, though I sometimes still screen the piece as a film/video installation, once even outside, in a forest, on the snow.

On the way to the river to shoot the underwater section in 1989, I made a quick call to my parents who live near the Saugeen to let them I know I was on the way up. My mother told me that my uncle had been found dead that day. He shot himself by the river (a different river), near our home town. She told me not to tell anyone because his immediate family wanted to say it was a heart attack. I got into the car with Garrick and Tim, my friends who were helping me with the filming, and we drove up. Churning inside.

I know that the death had something to do with what we filmed that day, and how I edited the section. I used the filming and editing as a way to mourn for him who I cared for, who never had the chance to be heard.

In this last section of the river, underwater, I gave up the camera. I told Garrick to let the river take him—just start the camera and let the current take you. I stood in the boat wondering about the death and watching. Giving up my hold on the camera.

Kitchener/Berlin: Or How One Becomes Two (Or None)

by Steve Reinke

I know it’s a hollow rhetorical ploy, a cliché even, an excuse for a certain kind of sloppiness, dispreparedness, but I mean it sincerely: I have given up on the essay I meant to write. Instead I submit these pathetic notes in the form of a letter asking for forgiveness. By now I should be used to my failure as a critic. I continually back away from planned essays, taking refuge in the literary: the aphorism, the satiric manifesto, the autobiographical anecdote. But this retreat is more disappointing than most. When I watched Kitchener-Berlin again (I hadn’t seen it in many years) I was struck by its rightness, its perfection. It seemed to me exemplary. Trebly exemplary: to (or as) the work of Hoffman, to Canadian cinema, and to experimental film. The film surely merits close textual analyses from a variety of approaches. Moreover, it seemed to me, however paradoxically, that these analyses would constitute a more general discussion of experimental film as an endeavor.

Apology

Sure, art is long and life is short, but I am not troubled by this condition. What bothers me is that art is complex and I am simple, though conflicted: stupid. Art makes retards of us all. Writing about it is a clumsy thing, doomed to always miss what is most significant and instead gloss the petty. Criticism becomes an act of contrition, an extended apology. I am sorry, and sorry that this is the case.

Film Contra Video

Experimental video is centered around the voice: an individual talking, rhetorically deploying a particular subjectivity in relation to a certain construction of consciousness. Video is willfully interior: its relation to the world is never direct, but processed through a particular subjectivity. It is doubly mediated, there is no direct perception, no immediate apprehension of the world. One cannot speak of phenomenology in relation to video without undue strain. Experimental film has a completely different relation to voice and the world. There is no such thing as a ‘personal’ film. The voice in film always aspires to be the voice of God. Film is singly mediated, self-consciously authored by authors who retreat behind subjectivity to become merely thinking, perceiving bodies. Interiority is impossible, the world itself impinges too strongly. Experimental video proceeds through a process of talking to one’s self as if one had a self; experimental film through a process of swallowing or incorporating the world into a self which is no longer human, but an author, a hollow signature attempting to structure perception.

Deleuze

This season it’s all about Deleuze’s cinema books. I keep reading these books because his distinction between the time-image and movement-image seems a fertile jumping-off point for a discussion of experimental film. But the only films people seem to discuss are Hitchcock’s (when Zizek via Lacan should have silenced them all, at least long enough so these hacks could take a break in which to think a little bit harder). I asked Laura Marks—one of the few academics who has applied Deleuzian theory to artists’ film and video—why this would be the case. She said because artists such as Hoffman are applying Deleuze’s insights directly (whether or not they have any knowledge of his writing) the need is not so great. This is probably true, but still I am not satisfied, and regret I am not able to supply such an analysis at this time. But here is what I have learned from Deleuze: that there is a kind of vertiginous ecstasy to be always on the verge of coherency, to endlessly defer sense in the hope that what one approaches is something that had been previously unfathomable.

Dream

I dreamt last night that I came across a book called Kitchener-Berlin and it was a really big book—lots of words, hardly any pictures, a few diagrams—something between an encyclopedia and an autobiography. It contained all the information about the images in the film, where they came from and what they mean. This dream is partly a response to my hermeneutic anxiety—a feeling that I can’t write about the film without a greater level of mastery, specifically the ability to form a reading which would proceed from an extensive knowledge of what is depicted in individual shots. So while I continue to remain firm that Kitchener-Berlin does not call for that kind of interpretation (that is, will not constructively yield to a directly hermeneutical approach), perhaps its dream book does (and would). Perhaps this dream book is a bible situated between the artist and the film and ready, in its encyclopedic detail, to tell us everything. We would study the book endlessly in order to derive increasingly accurate interpretations of the film. And the film itself—the hermetic, incorruptible art object—could sink into the background, as pure and coyly mysterious as the Mona Lisa.

Women, Nature and Chemistry: Hand-Processed Films from The Independent Imaging Workshop

by Janine Marchessault

The representation of nature has been a central and longstanding aesthetic preoccupation in Canadian art and iconography. Nowhere is this more in evidence than in a series of films that have emerged from Philip Hoffman’s Hand Processing Film workshop located on a forty acre farm in Southern Ontario. Since 1994, the films coming out of this summer retreat have been remarkable in terms of the consistency of their themes and innovative aesthetic approaches. One finds here a new generation of women experimental filmmakers exploring the boundaries between identity, film, chemistry and nature.

The creative context for these films is no doubt shaped by the Experimental films and critical concerns of Hoffman and his late partner Marian McMahon. Since the late eighties, both Hoffman and McMahon were interested in autobiography, film (as) memory and pedagogy. Hoffman, weary of overseeing large classes and high end technologies at film school, conceived of a different pedagogical model for teaching film production. Instead of the urban, male dominated and technology heavy atmosphere, The Independent Imaging Workshop would be geared towards women and would feature hand-processing techniques in a low-tech nature setting.. The process encouraged filmmakers to explore the environment through film, and to explore film through different chemical processes. The result is a number of beautiful short films that are highly personal, deeply phenomenological and often surreal. Dandelions (Dawn Wilkinson, 1995), Swell (Carolynne Hew, 1998), Froglight (Sarah Abbott, 1997), Fall and Scratch (Deirdre Logue, 1998), Across (Cara Morton, 1997) and We are Going Home, (Jenn Reeves, 1998) are among the most striking, recalling some of Joyce Wieland’s most artisinal works and the psychic intensity of Maya Deren’s ‘trance’ films.

By artisinal I do not mean the aesthetic effect of ‘home made’ movies produced by the uneven coloration of hand processing and tinting techniques. I am referring to the process of making films that is embedded in the final effect; that is, the work of film. Joyce Wieland’s work was often characterized as artisinal, a term that in the sixties and seventies was the opposite of great art. Famously, she made films on her kitchen table, bringing a history of women’s work to bear on her productions. In a video document of The Independent Imaging Workshop, three women sit at a kitchen table in a barn discussing the varying and unpredictable results of processing recipes: the thickness of the emulsion, the strength of the solutions, the degree of agitation, not to mention air temperature and humidity. Out of the lab and into the kitchen (or barn), film production moves into the realm of the artisan and the amateur which, as Roland Barthes once observed, is the realm of love. This is the home of the experimental in its originary meaning, of finding what is not being sought, of being open to living processes and to chance.

Like Wieland, this new generation of filmmakers is exploring the relationship between bodies, the materiality of film stocks and the artifacts of the world around them. The simple images of nature (daisies, fields, frogs, trees, rivers, clouds and so on) and rural architectures (bridges, barns, roads, etc.) are exquisite in their different cinematic manifestations. This is not idealized or essentialist nature, rather the landscapes are grounded in an experience of place. In Dawn Wilkinson’s Dandelions for example, the filmmaker speaks of her relation to her birthplace and to home, “I am Canadian.” As the only black child growing up in a rural town in Ontario, she was frequently asked “where are you from?”. As she tells us about her experiences of being connected to nature while not being included in the history of a nation, we see her with dandelions in her hair; she films her various African keepsakes in the landscape; we follow her bare feet on a road and later, she does cartwheels across fields. The montage of images is delicately rhythmic, and is accompanied by a monologue directed at an imaginary audience “Where are YOU from?…I was born here.” Like so many of the films produced at the workshop, the film explores the relation between the natural landscape and social identity.

Several of the films display quite literally a desire to inscribe personal identity and history onto or, in the case of Carolynne Hew’s Swell, into the landscape. In Swell, Hew, lying on a pile of rocks, begins to place the stones over her body. The film is structured by a movement from the city into the country, but the simple opposition is undone by both the filmmaker’s body and film processes. The quick montage of black and white city images (Chinatown, bodies moving on the street, smoke, cars), accompanied on the soundtrack by a cement drill, is replaced by feet on rocks, strips of film blowing in the wind and beautifully tinted shots of yarrow blooms. There is no attempt here at a pristine nature, at representing a nature untouched by culture. Rather, the film is about the artist’s love of nature, her sensual desire to be in nature. Shots of her face over the city are replaced with images of nature over her body; yarrow casts detailed shadows on her thigh, a symphony of colors abound–orange, blue and fusia. Strands of film hang on a line and Hew plays them with her scissors as one would a musical instrument. The sounds of nature–crickets, bees, water–are strongly grounded in the sound of her own body, breathing and finally a heartbeat. There are no words in this film but everything is mediated through language and through the density of the filmmaker’s perception and imagination. The film is laid to rest on a beautiful rock as she scratches the emulsion with scissors, the relation between film and nature is dialectical. Nature here is both imagined (hand processed) and experienced. It is impossible to separate the two.

Deirdre Logue’s two short and deceptively simple films, Fall (1998) and Scratch (1998) also convey the filmmaker’s physical insertion into nature only this time the experience is not sensual release, rather it is a sadomasochistic and painful journey. In Fall, Logue falls (faints?) over and over again from different angles and in different natural locations to become one, in a humorous and bruised way, with the land. In Scratch she is more explicit about the nature of her images as we read “My path is deliberately difficult”. Facing the camera, she puts thistles down her underpants, and pulls them out again. The sounds of breaking glass as well as the crackle of film splices are almost the only sounds heard in this mostly silent film. Intercut are found footage images from an instructional film, we see a bed being automatically made and unmade, glass breaking and plates smashed. This film is sharp and painful. Logue, beautifully butch in her appearance, is anything but ‘natural’; it is clear that the nature she is self-inflicting is the nature of sex. Her body is treated like a piece of emulsion–processed, manipulated, scratched, cut to fit. What is left ambiguous is whether the source of self-inflicted pain results from going against a socially prescribed nature or embracing a socially deviant one.

Sarah Abbott’s Froglight (1997) is even more ambiguous than either Swell or Scratch in terms of the nature of nature. The film opens with the artist’s voice over black leader, “I am walking down the road with my camera but I can’t see ,anything.” A tree comes into focus as she tells us “but I know I am walking ,straight towards something, we always are.” For Abbott there is ,something that exceeds the image, that exceeds her thinking about nature. She experiences a moment standing in a field, a moment that cannot be reduced to an image ,or words; ,she “experiences something that is not taught”, she does not want to ,doubt this experience because “life would be smaller.” Abbott touches the earth, we hear the sound of her footsteps, we see a road, we hear frogs, and later we come upon a frog at night. In the narration which is accompanied by the sound of frogs, Abbott attempts to put into words the idea of an experience that is beyond language, the idea that the world is much more than film, than the artist’s own imaginings. Like the soundtrack, the film’s black and white images are sparse. A magnifying glass over grass makes the grass less clear and is the film’s central phenomenological drive: surfaces reveal nothing of what lies beneath. Towards the end of the film, a long held shot of wild flowers blowing in the wind is accompanied by Abbott’s voice-over: “a woman gave me a sunflower before I came to make this film, and someone asked if it was my husband as I held it in my arm.” The ambiguity of this statement foregrounds the randomness of signs (flower, husband) and language. Froglight affirms a nature that is mysterious and unknowable, a world of spiritual depth and creative possibility.

What first struck me about so many of the films coming out of the workshop is the tension between the female self/body and nature; each film is in some way an exploration of the filmmaker’s relation to the land as place by cartwheeling, walking or falling on it, and in the last two films that I want to comment on, swimming and dreaming through it. Women’s bodies in Jenn Reeves We are Going Home and Cara Morton’s Across are not only placed in nature but in time. Temporality exists on two planes in all of the hand-processed films I have been discussing, not only in terms of the images of a nature that is always changing but also, in terms of film stocks and chemicals that continue to work on the film through time. Where workprints serve to protect the original negative from the processes of post-production, the films produced at the workshop use reversal stock and thus include the physical traces of processing and editing, an intense tactility that will comprise the final print of the film. This is what gives these films their temporal materiality and sensuality. In We are Going Home and Across this temporality is narrativized and it is perhaps fitting that both films experiment more extensively with advanced film techniques such as time-lapse cinematography, solarization, single-frame pixelation, split toning and tinting, superimpositions, optical printing and so on. Here is where these two filmmakers would part company with Wieland whose cinematic sensibility is, in the first instance, shaped by a non-narrative tradition. Both films are steeped in a narrativity that can be more easily situated in relation to the psychodramas of another founding mother of the avant-garde, Maya Deren.

In the films of Deren, nature and the search for self are always an erotic and deeply psychological enterprise. Dreams allow passage to a human nature and a mysterious self that cannot be accessed through conscious states. Her films have been characterized as ‘trance’ films for the way they foster this movement into the deepest recesses of the self, a movement that is less about social transgression as it was for the Surrealists, than about the journey through desire. We Are Going Home is a gorgeous surrealistic film that has all of the characteristics of the trance film and more. It is structured around a dream sequence that has no real beginning or end. The first image we see is of a vending machine dispensing ‘Live Bait’ in the form of a film canister.. A woman opens the canister to find fish roe (eggs). The equation of fish roe and film, no doubt a nod to the Surrealists, opens up those ontological quandaries around mediation and truth that Froglight refers us to. It is this promise of direct contact along with the return “Home” in the film’s title, that gives some sign that the highly processed landscapes belong to the unconscious.

The film is structured around a network of desire between three women. One woman dives into a lake and ends up feet first in the sand. Another woman happens by and sucks her toes erotically at which point everything turns upside-down and backwards. Characters move through natural spaces (the beach, fields, water) disconnected from the physical landscapes and from each other. Superimposed figures over the ground move like ghosts, affecting and affected by nothing. Storm clouds, trees in the wind, a thistle, cows are all processed and pixilated to look supernatural. Toe sucking complete, the second woman lies down under an apple tree and falls asleep, the wind gently blows her shirt open. A third woman, a dream figure, emerges from a barn; skipping through fields she happens upon the sleeping figure and cannot resist the exposed breast, she bends over and sucks the nipple. The film ends with a sunset and romantic accordion music that is eerily off key.

We Are Going Home is an erotic film whose sensuality derives both from the sublime image processing and from the disunity between all the elements in the film: the landscapes, the colors, the people. The sounds of birds cackling, water and wind that make up the soundtrack further intensify the film’s discordance. It is precisely this disunity that charges the sexual encounters which are themselves premised on an objectification. Home remains a mysterious place that exceeds logic and rationality; it is a puzzle whose pieces are connected in a seemingly linear manner but which will always remain mysterious.

In contrast, the psychic space in Morton’s Across is shaped through unity rather than disunity, the film is about crossing a bridge. The central tension in this lovely film, which accomplishes so much in a little over two minutes, is built upon a desire to connect with an image from the filmmaker’s past. The metaphoric journey forward to see the past is conveyed through a hand-held camera travelling at a great speed across a dirt road, through fields, along fences and through woods. Different color stocks combine with high contrast black and white images of the bridge while on the soundtrack we hear a river. As we travel with the filmmaker through these landscapes, we encounter a high angle solarized image of a woman sleeping in a field, a negative image of a woman swimming in the river below the bridge, a static shot of Morton staring into the camera, and home-movie images of Morton as a young girl running toward the camera. An intensity and anticipation is created in the movement and in the juxtaposition of the different elements. These are quietly resolved at the end of the film: the young girl smiles into the camera to mirror the close-up of Morton’s inquisitive gaze, the swimmer completes her stroke, stands up, brushes the water from her eyes and seems to take a deep breath.

The workshop films that I have written about reveal a renewal of avant-garde concerns and experimental techniques–they are unabashedly beautiful and filled with a frenetic immediacy. To some degree their aesthetic approach grows directly out of the workshop structure: location shooting and hand-processing. Participants (which now include equal numbers of men) are invited to shoot surrounding locations and to collect images randomly rather than to preconceive them through scripting. The aim of the workshop is not to leave with a finished product but rather to experiment with shooting immediate surroundings using a bolex and with hand-processing techniques. Many of the films produced at the workshop are never completed as final works but stand as film experiments—the equivalent of a sketchbook. This is the workshop’s most important contribution to keeping film culture alive in Canada. The emphasis on process over product, on the artisinal over professional, on the small and the personal over the big and universal which has been so beneficial for a new generation of women filmmakers, also poses a resistance to an instrumental culture which bestows love, fame and fortune on the makers of big feature narratives.

The Harvest of Philip Hoffman

by Janis Cole

POV magazine, Issue 58, Summer 2005

Living as Filming: Philip Hoffman interviewed

by Barbara Sternberg

BS: Hi Philip – When I saw What these ashes wanted (which I was almost afraid to see: would it make me cry over our loss of Marian; might I feel you had exploited Marian’s death for a film?), I felt it was your most successful film—most complete, most fulfilled in its methods and purpose. I mean that form and content were synthesized. (Of course, to be reminded of Marian’s liveliness and bravery in life as well as facing death brought sadness.) The film had a looseness, an openness (reduced use of the first-person voice-over, passages of silence, different types of footage and shooting styles, a relaxed episodic structure) that gave Marian, yourself and the audience respectful space. The film breathes, it’s organic-it moves forward, yes, but there are detours, meanderings in its progression. You have always done beautiful camerawork, but I could connect to this shooting and how it figured in the totality of the film more than in any other (Opening Series and Chimera have shooting I also love and seem to mark a change in approach). After the film I came home thinking how all your films carry forth certain inter-related themes: autobiography (film as constructed memory) which has been constantly examined since your first film Onthe Pond; the ethics of filming, most clearly stated as problematic in Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion; and death. The fear I had had of exploitation, a question of ethics, was addressed in the film’s dialogue:

PICTURE: SILOUETTE OF MARIAN ON HOSPITAL CURTAIN

MARIAN: …if you could have a ritual for death what would it be…and would it be private or shared.

PHIL: ..I think it would be shared.

CAMERA TILTS TO MARIAN’S EYES…THEN TO THE LIGHT

Opening Series dealt with authorial control, an ethical problem for you, by handing over the sequential ordering of its parts to the audience and to chance. I remember you’ saying, “Why should I have total control?” (One might also think of new music’s compositional principles of indeterminancy and chance.) The choice of order of the rolls gave an element of random chance and loosened the strength of narrative line.

PH: It was also to create a space where the audience, myself and the work could come together and manifest something. Each screening would be different not just because of the order of the work, but the order would reflect its audience. For example, I had shot some footage in Egypt of this Dutch companion that we met along the way who was filming Berber people holding up their tools and crafts. My filming of him, filming the Berber man, became kind of a critique because I included the photographer in the shot. That was shown at an event where he was present in Holland. So, not only did this become an issue when we discussed it after the screening, but there was also some kind of psychic manifestation that happened in the ordering. The way the other elements proceeded and followed this problematic image forced a particular reading of the situation. This was quite surprising. It’s like divining with the I-Ching. So, in Opening Series I was also trying to deal with these sort of invisible links between people, objects, in and out of art making.

BS: In Ashes you make editing choices and yet retain an openness. Space. This new openness is not only a strateg, but a place from which to make a journey, a film. (Is there a difference for you? Is living filming and vice versa? )

PH: I approach every film differently, so I’m not sure the next one will have the same kind of openness, though I think this is something that I have been developing since the early 90’s in films like Opening Series (1992-95), Chimera (1996), Kokoro is for Heart (1999), and most recently What these ashes wanted (2001) I suppose there is not the same need to say things so overtly as in ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) (1986), or in some of the collaborations I made in the 90’s where it seemed the process of collaboration and its outcome was more important than developing my own voice in the way I did in the ` looser films mentioned above. The 90’s for me was a time to try different ways of working but the most common element was collaboration, whether it be an aleatory collaboration with the audience who helped to place Opening Series in an order, or my `directorial’ collaborations with Wayne Salazar in Destroying Angel (1998), Sami van Ingen in Sweep (1995) or Gerry Shikatani in Kokoro is for Heart.

BS: The story (made up? I had assumed) of film kept in the freezer, unprocessed in ?O, Zoo! is told again, in What these ashes wanted, but this version and this time, it’s true – right? In Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) you questioned your right to film the death of a Mexican youth—at least text over a black screen told us this seemingly true story.

On the road dead lies a Mexican youth

I put the camera down…’

(excerpt of text from Somewhere Between)

In “…Ashes…” you say that just before Marian died you two slipped out of the hospital at night down to the lake’s edge, and here’s the photo of the lake you took.

I took a picture, you skipped a stone

(excerpt of text from What these ashes wanted)

But just prior to this we see a similar scene from a TV soap opera! Ethics, authority of the filmmaker, veracity, credulity, autobiography… So much of your filmmaking and teaching favors personal story-telling and yet you question both the ethics of film and the possibility of truth. Where does Ashes stand in relation to these terms and in relation to your previous films—and where do you think you place the viewer?

PH: The fallen elephant story in ?O,Zoo!, in which I film a dying elephant and then feel badly about filming it, exploiting the elephant for this sensationalistic act, and subsequently I put the film in the freezer—is a metaphor for what actually happened in my youth as the family photographer, when I filmed my grandfather in the casket at the request of my uncle. Subsequently, in horror at what I had done, I put the film in the freezer. I think when I wrote the story for ?O,Zoo! in 1986 I didn’t realise that unconsciously I was expressing this repressed traumatic experience. I found it quite curious that I had written a fiction, that had its source in a true story, which had happened, but that I didn’t know I was creating a stand-in for this difficult experience. The unconscious was pulling at my shirtsleeve, saying look here, remember this.

In Ashes, the Baywatch scene at the beginning of Part 3 mirrors the personal story of Marian and I leaving the hospital the night she found out she had cancer. The TV soap represents the way, through mass media, our culture presents grieving. Ashes offers another method. Some of Marian’s last writings, which I cherish, came after our final walk on the beach. She wrote in a way that told me that this was not just for her, but the writing should be passed on. In her grief, she had found out something that night and was offering it up. I was the one who could release it to the world through film.

TEXT ON SCREEN (black text supered over window):

The night we had our last walk

she wrote these words:

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

We come together separate

cry and look wide eyed bewildered…

I want to be near the water

We bundle up and leave the hospital for the beach

Beautiful clear crisp blue skied night

we mourn together

laughing at intervals

clinging madly to some sense of life

The open sky water makes me feel

part of something immeasurable

larger than me

and it is consoling

STILL PHOTOS OF MARIAN’S ROOM

(excerpt of text from What these ashes wanted)

So in a way, my films blend fiction with real life experience, and the fiction is usually grounded in lived experience. My sense is that once these expressions are mediated through the filmmaking, they are fictions anyway. I feel fine with this as long as what is made up is somehow a reflection of, or is based on, or comes out of a lived experience-which usually happens naturally. I try to let the experience of filming or photographing or recording audio, happen out of an authentic process of trying to find something out, or communicating something to someone. The residue of this process finds its way into my films.

I think Somewhere Between and ?O,Zoo! are dealing with ethics, but the starting points were traumatic moments that occurred while filming. I feel my calling is a filmer of life. A death occurs in front of me so I have to do something about the experience. During the filming of Somewhere Between I remember sitting on the bus with the camera on my lap, feeling the whole horrible experience. I chose not to film, perhaps more as a gut reaction, but when I returned to Toronto the aura of the boy’s death laid over me like a blanket. I wanted to still make a film about this sacred moment, which I had witnessed, without the so-called crucial image.

reaching out,

the white sheet is pulled over the dead boy’s body

the children wept…

the little girl

with big eyes,

waits by her dead brother

big trucks spit black smoke

clouds hung

the boy’s spirit left through its blue

(excerpts of text from Somewhere Between)

BS: So, in a way, all your films exist to have the audience at some moment wonder: what is truth? What is fiction? What is film? Is this truth? All of those things are floating around. As audience we go in and out of being sucked into the film the way mainstream films tend to operate on us, and then we’re conscious that this is a construct, that there are certain clues within it that make us say, Wait a minute… and give space to interact with the film. Reality is the interaction between us and this thing you’ve put out called a film.

PH: You asked me earlier if I brought the camera to the hospital to film Marian. The answer to this question expresses something of how I work, of my process. Marian was in the hospital. It was the fall of 1996, `the days of protest,’ and she was mad as hell at the Harris government and all the cuts that were occurring to the social programs. This also effected her directly `on the floor’ in the hospital she was in. She was trying to write a story about all this and she was taking pictures of herself in the hospital.

After Marian’s death, I developed the roll she had taken in the hospital, and found this picture of her, in silouette. She took it of herself in silhouette against the hospital curtain. She also filmed the same curtain from the same angle, and left herself out. Blank. The picture made me shudder. Most often, the powerful personal images, which I use in my films, have had other purposes.

Sometimes I do find it necessary to ask family or friends if I can use a particularly `personal’ recording. In an earlier work, passing through/torn formations (1988), there is a sequence about my …uncle and his daughter, who had not seen each other for sixteen years. I met him in his pool hall hangout and told him his daughter wanted to see him. He said he’d flip if he saw her so instead he gave her a present. I followed him into the drugstore and he found this mirror that was in two parts, that folded into itself – a ‘corner mirror’ he called it. He felt it showed you the ‘real’ reflection of yourself, ‘the real you.’ It technically does this since it is constructed as two separate parts, the image of yourself, though severed, reflects into itself, thereby rendering your portrait normal, like a photograph. Your face isn’t reversed in the way a normal mirror reverses your features. In exchange for the corner mirror she wanted to send her father a recording, so I taped her message to him. It was my idea to also tape her looking into the ‘corner mirror,’ describing her own facial features. I found him again, and we listened to it in my car. He was deeply moved. A few years later when I was finishing the film I asked her if I could use her voice from the recording and the film we shot of her looking into the corner mirror, and she agreed. As for my uncle, we spent some evenings looking at different cuts of the film, while he played music to it. I used his music in the film. Later I showed him parts of the finished film, but he was most interested in the music. I had thought the film could be a vehicle for me to get to know my uncle again, who used to take me fishing and teach me accordion when I was young. I guess it did somewhat, but it was a bit romantic on my part. I was young when I started this film, around 25. Anyway, I find that this kind of material works well for me as it kind of rings true. It is the residue of lived experience. When I start imagining something that I should film, and then I carry it out, it often seems contrived and it’s often not as exciting as working with what comes along.

BS: When I used to be the photographer for a friend’s wedding or anything like that, it kept me at a remove, this in-between space of the camera, between the event and me.

PH: It is the event. Everyone is using images, looking at pictures and video. It’s not once removed, and it is as authentic a moment as any other. The question is how to position it within your experience.

BS: It’s how you interact.

PH: It’s how our culture interacts.

BS: Your first film On the Pond (1978) starts out with you and your family looking at family slides, and on the soundtrack we hear your family commenting and reacting.

PH: Yes, to me this is a continuation of an oral tradition I learned from Babji, my grandma. She would talk to us about our dreams at the breakfast table. The difference is I use a tape recorder and transport conversations through my films.

BS: I want to go back to the term “autobiography”. You’ve made a home movie, a road-movie, a making-of-the-movie movie. I guess your films are autobiographical in that they represent the truth of how it is for you, subconsciously, psychically, spiritually, as well as materially. Do you feel the term autobiography is applicable to you?

PH: I don’t use it much because autobiography assumes that it’s just about yourself. My films are about people and places around me, though strained through my perception. When a writer uses material from their life in a novel, we do not call the book an autobiography. I suppose we might say there are autobiographical elements in the work, but that is common with most art. It is only that the photographic or electronic image is a good stand-in for the real, so we cannot get around the fact that people depicted in a `documentary’ are actually and fully ‘on the screen!’ But we know it’s still an expression or reflection of the person, of the originating moment. Films are constructions, and in my work I construct characters out of the residue of real life experiences.

BS: As Godard says: Film is truth at 24 frames per second, all film is fiction. Do you think the focus on death in your work is because of your personal experiences with your grandmother and Marian?

PH: Everyone experiences a death close at hand but not all filmmakers deal with death so directly, or so often. Maybe it was this initial experience filming my Grandfather in the casket. You know we spend our lives working through this mess…. whether it be a difficult birthing or a difficult family relationship. I’ve said before that childhood is so traumatic, most of us sleep through it… maybe the next part of that statement is that we spend the rest of our time consciously or unconsciously shedding this inevitable pain. I’m glad I have filmmaking because it seems to be a good place to put all this stuff. Maybe I was marked by that experience and I have to keep pushing the rock up the hill—my karma?

BS: Do you think it has something to do with your Catholic upbringing (we saw you at your first Holy Communion in both On the Pond and Kitchener/Berlin)?

PH: What I think my Catholic upbringing taught me was that bread can turn into body and wine can turn into blood. The material and the invisible (spiritual?) are interchangeable, certainly one isn’t more important than the other. My films, like many experimental films, take on a form that honors what we can’t see with our eyes. I work with the photographic image, this art that can represent real material objects/beings most precisely, but eventually my intent is to shed light on the things we can’t see.

BS: …or your German ancestry? The reason I mention the German ancestry is because a couple of times, in passing, you’ve made a comment to me about your name Hoffman, and that the name Hoffman is German… and I thought, perhaps, you were saying it to me because of my Jewish background.

PH: Right.

BS: And that was a link between us to that history.

PH: Yeah.

BS: And what to do with that? The burden of that history.

PH: Yeah. Yeah.

BS: So, the reason I mention it here is because, certainly recent past German ancestry calls up the Holocaust, and the Nazi period. I don’t know if that’s on your mind at all, as a burden.

PH: Well, it’s in passing through. It’s easier to deal with on my mom’s side, which is Polish—the occupation her family experienced in their homeland by the Germans. There are two stories in passing through, but it’s not dealt with directly, only as a part of the family’s shared history. I also have some old 1/2 “tapes of my German grandma looking at photos from her past and talking, so they may be a vehicle to deal more deeply with this subject.

BS: Films to come?

PH: Maybe.

BS: Are the encounters with death the catalyst for making the films? I recall Bruce Elder pointing out (in a class he was teaching) how Michelangelo Antonioni’s protagonists are separated from others and the flow of daily life by an encounter with death which gives them a different awareness.

PH: When the death of a loved one occurs you do go into a different space, and I did film some moments within that space after Marian passed away. However, I am not only in a movie, I’m also looking at my own experience from the outside as I construct the film. Certainly as time passed, my own state changed. As I make my films I’m dealing with people directly, my filmmaking is social, I’m sharing it with the world. I’m making this work and I’m showing an installation of it in Finland and Sydney. I’m not separated from the culture, I’m embracing it, trying to find a ritual to deal with death which makes sense to me, and I hope others. This makes more sense to me than the funeral parlor, the casket, and going into a room with all the flowers and everyone afraid to say anything.

BS: I remember at Marian’s memorial service. I was really enriched, and felt I had gained so much from it. But my initial reaction when you showed a film during the memorial was, I was taken aback. I thought, he’s showing a film at her memorial?! But by the end of the whole service, with everyone contributing in their own way, I felt that I had been enriched, and educated, and moved.

Ph: Well, I felt it was the only thing I could give because I couldn’t talk. It was just a poem about her first coming to the farm, and a kiss.

BS: With Opening Series and Chimera and now Ashes your shooting has changed. The camera is much less stable, more fluid and animated with shorter takes. Where did this come from? Do these signal filmic and/or philosophical developments?

Ph: I started shooting in short bursts in Chimera (and in some sequences of Ashes) around the time the wall was coming down in Eastern Europe, and the Internet was going up everywhere. My drive to fragment came from a perception that something was breaking down…well so was my reliance on the photographic image as document, as opposed to expression. I think in Ashes I maintain a better balance between these two aspects which I hold a high regard for. When free association becomes the mode of perception, which is the only sensible tool when so much is up in the air, making a mosaic film is more apt to navigate this space we live in, as opposed to the page-turning form of linear narrative. You’ve also been working in this way, evoking a kind of present-ness…

BS: With presence. When I started shooting in short bursts and single frame it was to achieve a simultaneity of place and time I think of as reality, a relatedness, which I had approached in earlier films by superimposition. Now I was trying ‘editing’ closer and closer bits. It also came from a view of myself/filmmaker as observer rather than master or in control.

PH: There have been some great developments in this kind of work, like Brakhage. Trying to develop a spiritual space for living/filming in` the now. I love his film Black Ice and theArabic Series, and in your work I love the present-ness in Like a Dream that Vanishes. As a viewer we’re not thinking about what has happened, or what might happen. We’re right in the moment.

BS: Part of my thinking about that was if you get past the identification of what the image is, or what the narrative information of that image is, then you can get closer to a sense of being.

PH: And the flow of time.

BS: Yes, yes. That it keeps going, and you can’t stop it and hold it, and study it.

PH: “Time goes…” as Aunt Katie says in one story in Ashes. In Like a Dream that Vanishes you break it up with observations of the philosopher, John Davis, who you filmed. I think it really works, because you weave these rushing images throughout, and then we’re back listening to him talk about the `mess’ of experience…and of course we realise it’s a mess because it can’t be controlled….because living in the present is the roller coaster you can’t control.

BS: This way of shooting and making allows the complexity and wonder in. I’ve been thinking of the structure of Ashes which is more episodic than earlier works. Sequences sometimes have a loose connection, (besides being different shooting styles), but aren’t firmly attached to the preceding one. The connection isn’t justified with causality, although they seem to belong. Some were little detours and gave a bit of relief from the story of Marian’s passing. Like the Egyptian interlude. The sequences stood on their own, and yet they seemed to fit together into a whole. I felt there was a whole-ness to it, despite the fact the sequences could be quite independent. I’m wondering how you determined the structure, how you selected what to put in, and how you ordered it?

PH: It was a long and organic process that started in 1989. I was shooting single frames—zooming on each exposure to create a splayed image There were a number of projects that came out of this way of shooting: Opening Series, Chimera, and some installation works. When you are shooting without a plan, just collecting images from your life, there tends to be an organic connection between life and work.

BS: There is a unity in all your work, because you’re you.

PH: Rather than because it’s a project you are working on. As the 90’s moved along, I started working on Destroying Angel with Wayne Salazar, which Marian assisted through her talks (and recordings) with Wayne. Suddenly in the middle of it Marian tragically died. After a time, Wayne, who had a strong connection to Marian, asked me if we could use some of Marian’s story in our film, which I agreed to. At the same time, I had been asked to construct an installation in Finland. When Marian passed away, I felt I couldn’t really make the trip, but my friends there called me up and suggested I come, they’d take care of me. Since I was spending so much time going through all of the images we had together over our life, why not create something out of it? It seemed to be a positive space for me, so my friends in Helsinki helped me make a kind of offering to her, a six screen circular work, in which many of the ideas for What these ashes wanted developed. My process of finding the structure for Ashes came out of these projects which I was immersed in after Marian’s death. It just seemed to be the way I wanted to spend this grieving time. At the beginning of Ashes, there is a recording from my answering machine from Mike Hoolboom, who gracefully relays to me a story about the repairing of a precious piece of pottery, and I thought that I was trying to do the same thing with the film, with my life. To show something of beauty from a life that had been shattered through her death.

HOME MOVIE (SLOWED DOWN) OF A WOMAN (MARIAN) WALKING PAST COLUMNS IN FRONT OF EGYPTIAN MONUMENT

SOUND (TELEPHONE ANSWERING MACHINE):

MIKE: Hi Phil, I found this in a book and thought you might like to hear it, hear goes.

When I call up pictures of friends, lost, a terrible ache comes over me, so much so that it has to go away on its own, there isn’t much by way of remedy that I can do. I remember a letter of Henry James where he said that in times of great grief it was important to ‘go through the motions of life’; and then eventually they would become real again…. I’ve been trying to write myself a poem about those ancient Japanese ceramic cups, rustic in appearance, the property at some point of a holy monk, one of the few possessions he allowed himself. In a later century someone dropped and broke the cup, but it was too precious simply to throw away. So it was repaired not with glue but with a seam of gold solder. And I think our poems are often like that gold solder, repairing the break in what can never be restored perfectly. The gold repair adds a kind of beauty to the cup, making visible part of its history….

(Taken from a portion of a letter from the poet Alfred Corn, Feb 19, 1994 from the novel Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty.)

OK I guess that’s it. See you later.

At times I think this could come off as crude, using filmmaking as a process for grieving but felt it was a way of honoring her. I went to Spain to try to find the rock opening which is seen at the start of the film, with her text superimposed, where she realizes her illness. I found this text paper clipped behind a still image of this hole, which seemed to be a cave in Guadelest, Spain. I journeyed there with her friend Belinda and we had great trouble finding it. I felt they must have removed it some how, until I looked down on the ground and saw this tiny opening, exactly the same shape as the photograph she took. We had a laugh imagining her down on her stomach trying to take this picture.

The film’s structure came after Marian’s death when I was spending this time remembering her, and bringing this film work around to friends and strangers.

BS: There was one sequence in the film, where you’re in the back seat of the car taping Marian while she works as a nurse visiting people’s homes. I thought it was a very interesting scene for its mixture of realities. Marian’s a nurse, she’s going into people’s homes, and yet this is being filmed, so is this staged for the film? No, this is real, and we’re seeing it being filmed. This scene sets up the whole question of veracity, what is real and where is the real located?

PH: Yes, that’s the synch scene where I sit in the car with this huge 3/4 inch camera, circa 1983, filming her reactions to what she has just seen on a particular home visit. She was giving up nursing so she asked me to videotape her on her last day on the job.

BS: At one point, as I recall, Marian chastises you, or gets mad at you, because you’re not answering her question.

PH: Mike Cartmell remarked that what is strong about the film is that it honors not always only her good side. You know, she was a pretty tough cookie. And it doesn’t show her necessarily in the best light, which of course, is the best light, because it was part of her. I’m in, probably, my late-twenties, and I’m saying. Yea it’s hard, the camera’s heavy. And she says, that’s not what I mean, it’s hard emotionally. It’s hard for me to be filmed, and she chastises me, and in a funny way, makes fun of me.

BS: And leaving this in gets more at this question of, where is the real in a situation? She’s saying that you answered in a superficial way. It’s an awkward situation because the camera is heavy, but she was trying to get at something below the surface. I think it’s very typical not only of your process of filming, but of Marian’s whole project of digging beneath the surface. How do we come to knowledge? What forms our sense of what’s real and true? This episode functioned on a lot of levels. I’m wondering how you see this scene functioning in the film.

PH: Well, it introduces her ‘in the flesh,’ because it’s sync sound. One of the ways that I want to represent her is as a physical being, closer to, let’s say, a realist representation of her.

BS: So it’s Marian. But its also any of us, in a sense. I mean, the film is about you and Marian, and what happened, but what if I don’t know Marian?

PH: If you didn’t know Marian, now you actually see her in the flesh. So it’s serving this purpose in the film… you are introduced to the loved one who has been lost. This is why I like to blend various forms, for example, synch sound with a more impressionistic sequence. These are different aspects of how we perceive.

But I think the purpose of this scene coming at the beginning of the film is so that there is ground to stand on for the rest of the film. We are introduced to this person in this way, twice. She comes back again, `in the flesh,’ in synch-sound talking in front of the palm trees, and again she is questioning, but mostly I like that scene because we can see her mind working…..she is constantly discovering something for the camera, which brings her to life for a brief moment.

BS: And it would seem that the process of making a film is the questioning part of the experience for you.

PH: Yeah that’s right.

BS: We’ve talked about Chimera in terms of it having been a film in three parts, and used in an installation, and now parts of it finding its way into Ashes. I just wondered how you saw that footage functioning in this film.

PH: Well, the single frame zoom footage is carried forward into Ashes, because it carries the three deaths that occurred when I was filming that way. In the early 90’s, three times death came in front of me. This occurred in 1991, 1993, and 1994. I found it strange that this kept happening, and that it was always connected to my filming. I brought these stories and this shooting forward into Ashes, because they seem to serve as a kind of premonition of death, and though one cannot really be ‘prepared’ for the death of a loved one, it seemed to make me aware that something was coming. I am troubled by these thoughts because two people died, and one nearly, which is horrific and sad. I still do not have an explanation for this so it sits in the film unresolved, like so many things in our lives….

BS: The style of that shooting, for me, points to the ephemerality of life. Each second is over, it’s not something we can hold in our hand. Whereas a still photograph gives you the illusion of having something, but really you have something out of time, and so very death-like, whereas this is alive, this is present, and yet you can’t have it.

PH: Now you see it, now you don’t. It is like that.

BS: There’s also image-to-image speed, because it’s not a single image that you zoom into and out of.

PH: Past, present and future exist at the same time, which is maybe what death is, or what happens after death. There is no form, no linear time.

BS: I also want to talk about the slow motion sequences.

PH: The first part of the film is book-ended by a shot of Marian running in slow motion, first in colour, then in black and white. As if she keeps fading, but is also eternally returning. These are representations of the dream space one is in when one has psychic trauma. She did keep coming back in dreams, or in waking life, or absurdly through the ladybug form. Just like a photograph which actually reminds me that she is gone. It is often said that photos, films or sound recordings help us to understand the past. Well, I think they also help us get through the present. Diving into this kind of footage after Marian’s passing seemed a good place for me to be.

BS: Between teaching at Sheridan College and now York University and at the Film Farm workshop, are you creating a movement within experimental film with a manifesto or credo that you espouse?

PH: I try to create a place where people can meet and be together. If it’s a movement it’s a movement of sympathy towards each other, or a place to be, where people are working together instead of tearing each other apart.

BS: Competing.

PH: Competing, or spending so much money to make a film. A place where making something is the most important thing. So I wouldn’t say that is a manifesto, but it is a place where I feel right. The farm workshop is set up so that people need to be there for the whole time, so it’s a retreat. They need to come without a script, and part of the idea is that there is a film inside and no matter where they are, it can be coaxed out. In the time they spend at the workshop they can make a start on that, or finish it, wherever they end up at the end of their stay. Participants learn certain processes, working with a Bolex, with light, with hand processing and tinting and toning. They don’t have to worry about getting it exactly right, sometimes the accidents help them find their route. It’s a bit like cooking, tasting what you’ve done, adding a few more spices here and there.

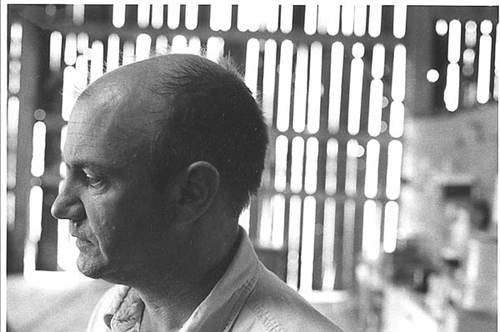

BS: I thought we could call this interview “Man with a Movie Camera” and use the photo of your silhouetted torso with swinging arm suspended by a Bolex-holding hand. I think you’ve had an image of you-with-camera in every film you’ve made. Is this honesty (this film is made by someone, it’s not objective truth) or autobiography (and that someone is me)? Is your life lived through making a film of it?

PH: Isn’t it something like a signature? Though this moves against the idea of giving up authorial control. But I think there is something important for me about being able to see where I’ve been through my films, and my life, and the people who have taught me things.

Local Spotlight, Philip Hoffman diarist filmmaker

by Monica Nolan

Indie Circuit, ReleasePrint, March/April 2004

A Dream for a Requiem

Filmmaker documents pure emotion

REVIEW

WHAT THESE ASHES WANTED

Peter Vesuwalla

Philip Hoffman’s What These Ashes Wanted is one of those films that forces you to rethink the medium. There are pictures, yes, and movement, light, and sound. There is, however, no narrative, and yet there is emotion. Both of these last two points are remarkable.

To make a film that is genuinely non-narrative is no small accomplishment. At a recent exhibition of short films, I listened as budding visual artist Victoria Prince attempted to explain that there was no narrative link among the images in her latest experimental video, despite an audience member’s insistence that he had been told a story. Last year, soi-disant “guerrilla projectionists” Greg Hanec and Campbell Martin were forced to concede that people will find a story in their work provided they look hard enough: audiences tend to do so. The fact is, there is something hard-wired in the human psyche that forces us to find continuity where there is none.

What makes What These Ashes Wanted unique and interesting is Hoffman’s ability to override our inherent expectation of being told a story. We learn that his longtime partner, Marian McMahon, has died of cancer, and that the film is an expression of his grief, but that’s only what it’s about. Nothing actually happens in it, just as nothing in the physical universe happens to us while we’re sitting and reflecting on the past. It’s assembled from nostalgic pieces of video footage, bolex film, still pictures, words, music, poetry and seemingly random micro-montages that fade into obscurity like fragmented memories.

“In times of great grief, it was important to go through the motions of life,” he narrates, recalling author Henry James. “Eventually, they would become real again.”

Hoffman edits these motions together the way that Jackson Pollock paints. He expresses his grief over his lost loved one not through the images themselves, but through the physical act of filming them. The images such as an empty room, an inventory of mementoes, and a field of sunflowers, coupled with a mournful monologue and a montage of unanswered voice-mail messages, carry all the weight of emotional brush strokes. If Pollock was an “action painter,” then Hoffman, I suppose, ought to be called an “action filmmaker;” that label, however, might cause confusion. Instead, call him a documentarian of the human soul.

Philip Hoffman will be on hand to present What These Ashes Wanted, along with his pupil Jennifer Reeves’ We Are Going Home, on Thursday, May 17, (2001) at 7:30 p.m. at the Cinematheque, 100 Arthur St.