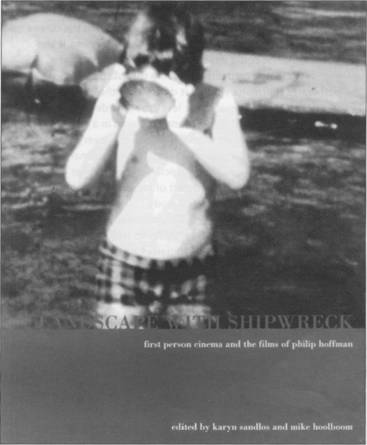

by Elizabeth Johnston, edited by Karyn Sandlos and Mike Hoolboom

Book Review

LANDSCAPE WITH SHIPWRECK is a book that acts upon the reader with an uncanny ability to engage both the emotions and the intellect. Quotations from diverse sources are liberally sprinkled throughout thebook, point and counterpoint, making a sort of contrapuntal music. Lifting you up, confirming, lulling, exciting and sometimes terrorizing you. So many times I had to stop and pluck a quote from this rich veinand write it into my journal for safekeeping. What Hoolboom and Sandlos say in their introduction is true:”By reading this book, you risk making this story your own.”

LANDSCAPE WITH SHIPWRECK is a book that acts upon the reader with an uncanny ability to engage both the emotions and the intellect. Quotations from diverse sources are liberally sprinkled throughout thebook, point and counterpoint, making a sort of contrapuntal music. Lifting you up, confirming, lulling, exciting and sometimes terrorizing you. So many times I had to stop and pluck a quote from this rich veinand write it into my journal for safekeeping. What Hoolboom and Sandlos say in their introduction is true:”By reading this book, you risk making this story your own.”

The story of a third-generation Canadian experimental filmmaker, Philip Hoffman, is literally (or academically) told to us in Peter Harcourt’s informative look at one member of the so-called Escarpment School. (Included in this school are filmmakers such as Rick Hancox, Carl Brown, Gary Popovich, Marian McMahon, Steve Sanguedolce and Richard Kerr.) “Born and raised along the craggy slopes of theCanadian Shield, their work typically conjoins memory and landscape in a home movie/documentary-based production that is at once personal, poetic and reflexive.”

A self-styled autobiographical filmmaker, Hoffman has been using 8 and 16 mm cameras to film his family since he was in his teens. Despite the very personal subject matter, Hoffman’s work is a testament to how the specific can be the universal. One of his first “assignments” was to film the corpse of his dead grandfather. (Although he did the filming, it was years before he could develop the film.) Death, and theabsences created by death, including the loss of memories, permeates Hoffman’s work as it does this anthology.

All of us struggle, at some level, to some degree, with identity, memory and the challenge of living in a world where every second all around us things are dying – every second dropping beyond our grasp. Simultaneously, Hoffman’s work performs the double role of magician and embalmer – recreating memory and in the very act of recreation fixing that memory as an embalmer fixes a body. This idea is beautifullyarticulated by various writers, but particularly in “Thin Ice” by Karyn Sandlos,”Notes on River” by Philip Hoffman, and Brenda Longfellow’s “Philip Hoffman’s Camera Lucida.”

Ronald Heydon’s “The Landscape Journal,” is indicative of the emotional responses in Landscape. Using Hoffman’s films as a springboard, Heydon ruminates on his own connection to land, memory, and autobiography. In a particularly moving entry, Day 8, Heydon discusses whether a camera should record death, which is for Hoffman a central preoccupation. Hoffman’s film Somewhere between Jalostotitlan andEncarnacion is the source of this entry. In this film, there is no narrator, but intertitles tell us the story. At one point, the bus Hoffman is on stops because a boy has been killed in the road. Hoffman thought about filming the death, but decided not to and the resulting film is, in some measure, an attempt to come to terms with that decision and the lacuna it creates in the film itself. Heydon, watching the film, remembers his travels in Italy as an 18-year-old. He’d hitched a ride with a jocular man who preferred back roads to highways.

Just ahead of us on the narrow road, an older man on a bicycle. We try to drive around him, but the man turns left (doesn’t he hear the truck?) and we drive right over top of him. We sit there, immobile and white. There is not a sound. I get out of the truck and see children running from a neighbouring farm. The man is dead. The young Italian can’t face him; he stands and weeps. I hold him and watch the children’s silent faces that look at us as if we were murderers… I thought I would never forget the look on those young faces, but I did forget until Hoffman’s film brought them back.”

To film or not to film death, that is the ethical question that resurfaces throughout Landscape. In slightly more comic (or objective?) tones, this question is revisited in Hoffman’s documentary of Peter Greenaway’s A Zed & Two Noughts during the filming of which an elephant died on location at the Rotterdam Zoo. In Hoffman’s documentary, the story of the elephant dying is told over a black screen. The narrator says he filmed the elephant, but couldn’t bring himself to develop the film and so put it in the freezer. Yet, after the credits, there is a shot of an elephant getting up from the ground that throws into question the veracity and authenticity of the film.

While there is no doubt such treatment of actuality gives rise to ethical questions, the consensus seems to be (exemplified by Michael Zryd’s “Deception and Ethics in ?O, Zoo!,” and Polly Ullrich’s “The Workmanship of Risk” among others) that the censorship of such methods would deny filmmakers and viewers the opportunity for questioning the ways of the self. Hoffman explains it this way:

By means of the personal content of my films I seek to uncover subjective aspects of the way events are recorded. Focusing on the way that l, as afilmmaker, can and do influence both form and content allows room for the viewer to reflect upon ways in which meaning is constructed in film. Using the processes of reflection and revision, I seek to examine and express how we bring meaning to past and present lived experiences.

Hoffman’s films demand a sophisticated, or at least an open-minded viewer, one that, given the recent documentary scandals in Britain, does not yet exist in the mainstream.

In the act of reading this book, an open mind, a selfreflexive mind, will find itself transformed and changed. The old self will no longer exist. And, only after reading to the end will some things at the beginning become clear like the nature of this change and, also, the meaning of this rather odd statement:”In biblical times,” write Sandlos and Hoolboom,”there circulated rumours of a book so fearsome, so awful, that its reading would occasion the events it described, and end the world as it was known. I have no doubt that for Phil, this is that book. I pray he never reads it.”

I was nearly put off by that apocryphal introduction. It seemed too large a statement for any book to live up to let alone a ragtag anthology of”critics, architects, and builders.” I tell my students of fiction writing: You have to earn the right to use abstractions, cliches or exaggeration.To my delight, Sandlos and Hoolboom have earned that right. But, I don’t know that Philip Hoffman would feel things were over for him after reading this book since in the early nineties, he killed off the author in his own work and moved into collaborative installations, thereby rising from his own ashes. I suspect that Hoffman could use this book as confirmation of that transformation or at least keep it handy to stoke the fire needed for the next transformation.— POV

Elizabeth Johnston is POV’s resident book reviewer. She also freelances for major newspapers and teaches cinema in Montreal.