The Gāyatrī mantra of the Ṛigveda sets-up the entire short film: it is the mantra itself that creates the atmosphere of darkness, followed by the first creation: the tree, which contains the identity of darkness as if it were its visible matter…. (see below) “Deep 1” Ribalta Film Fest Review

`Deep 1′ preview

DEEP 1 (2023, 15 min, HDV or 35mm)

Hoffman on `Deep 1′

…more on Hoffman’s films

Stan Brakhage on `passing through/torn formations’

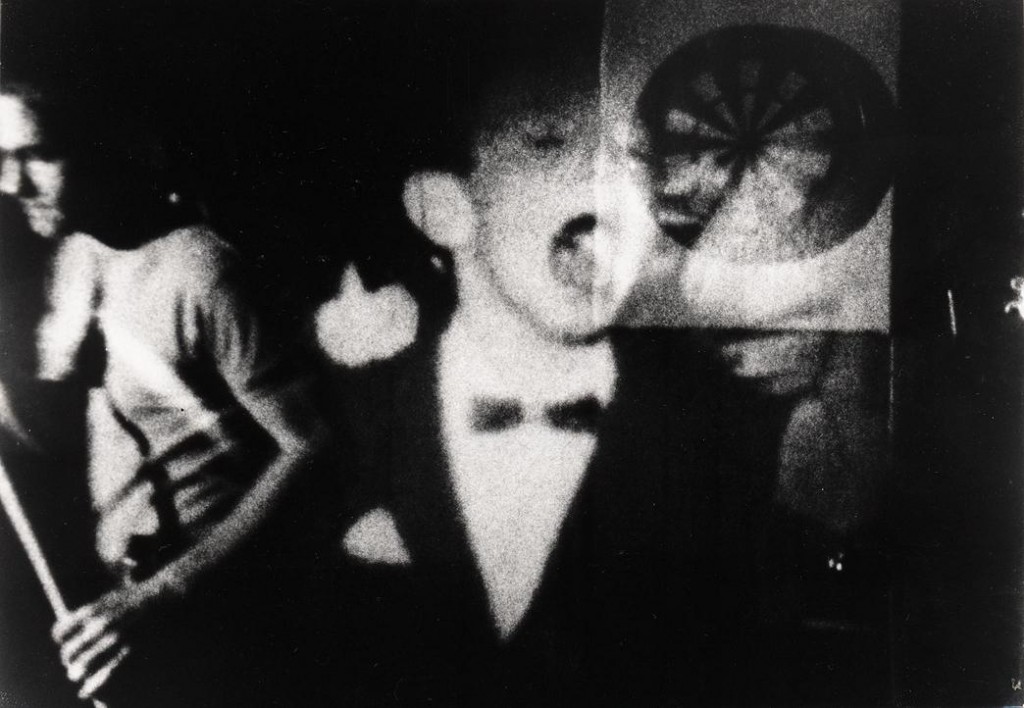

“passing through/torn formations accomplishes a multi-faceted experience for the viewer—it is a poetic document of Family, for instance—but Philip Hoffman’s editing throughout is true to thought process, tracks visual theme as the mind tracks shape, makes melody of noise and words as the mind recalls sound.”

PASSING THROUGH/TORN FORMATIONS (1988)

`passing through/torn formations’ preview

Mike Hoolboom on `passing through/torn formations’

Hoffman’s sixth film in ten years, passing through/torn formations is a generational saga laid over three picture rolls that rejoins in its symphonic montage the broken remnants of a family separated by war, disease, madness and migration. Begun in darkness with an extract from Christopher Dewdney’s Predators of the Adoration, the poet narrates the story of ‘you,’ a child who explores an abandoned limestone quarry….The film’s theme of reconciliation begins with death’s media/tion—and moves its broken signifiers together in the film’s central image, ‘the corner mirror,’ two mirrored rectangles stacked at right angles. This looking glass offers a ‘true reflection,’ not the reversed image of the usual mirror but the objectified stare of the Other. When Rimbaud announces ‘I am another’ he does so in a gesture that unites traveller and teller, confirming his status within the story while continuing to tell it. It is the absence of this distance, this doubling that leads the Czech side of the family to fatality.

complete Cinema Canada review by Mike Hoolboom on `passing through/torn formations’ Continue reading Deep 1 @ Simon Fraser University, B.C. & Ribalta Fest, Italy (Review)