by Philip Hoffman

Monthly Archives: October 2014

Images Talk (April 2001)

DARKROOM

Thirty years ago Richard Kerr and I set up a darkroom in my basement and I suppose it was there where I became drawn in to photographic processes… I have always been excited by that moment when the print is put into the developer and the image begins to appear. It’s a fleeting moment when change is most focused and visible and I suppose I’ve continued to dwell in that moment of transformation in my filmmaking…

Here’s an excerpt from passing through/torn formations, it’s Christopher Dewdney’s poem Out of Control: The Quarry:

“It is a warm grey afternoon in August. You are in the country, in a deserted quarry of light grey Devonian limestone in Southeren Ontario. A powderery luminescence oscillates between the rock and sky. You feel sure that you could recognize these clouds (with their limestone texture) out of random cloud photographs from all over the world. You then lean over and pick up a flat piece of layered stone. It is a rough triangle about one foot across. Prying at the stone you find the layers come apart easily in large flat pieces. Pale grey moths are pressed between the layers of stone. Freed, they flutter up like pieces of ash caught in a dust devil. You are splashed by the other children but move not.”

(from Preditors of the Adoration, Out of Control: The Quarry by Christopher Dewdney)

In passing through/torn formations I tried to create a form that wasn’t frozen or fossilized (as film tends to do)… and this was accomplished through the layering of dialogue and collected sound, the layering of story, the repetition of story, superimposition (sometimes three separate image systems on the screen at the same time)… It is my hope that this polyphonic form allows for participation from the audience, and at the same time suggests that all family stories have several perspectives, there is no such thing as one objective fact/truth, or way of looking at things…

I suppose this open form is taken up further in Opening Series where the audience orders twelve boxes like this and determines an order (there is an interrelated film in each box)… each time the film gets played there is a new order, and I track the various orders as the film screens… What I learn through Opening Series often finds itself in other films. For example, some sections in Opening Series 2 and 4 find themselves in What these ashes wanted, a somewhat more narrative driven film, so it’s a kind of testing ground for images as well.

I have taken up a method borrowed from Adrienne Rich’s feminist dictum: Collect Reflect Revise. The method of collecting is spontaneous and non-scripted, in which I try to dwell in that fleeting moment, watching time through the lens…

GINSBERG

In the early 1980’s, Allen Ginsburg gave a talk and led a meditation at Ontario Institute for Studies in Education and recently I found the tape I had recorded and played it for Janine and she bounced it into Public’s recent Lexicon issue. Here it is.

“It is possible through mindfulness practice, to bring about some kind of orderly observation of the phenomenology of the mind and to produce a poetics. From that instant by instant recognition of thought forms comes a notion of spontaneous poetry which Jack Kerouac and Gertrude Stein practiced. And that form of poetry is a form of Oriental form that is composed on the tongue rather than on paper. It is also a Western form, a very American form. Blues and Calypso poetics were always made up on the spot. There always was a formulaic structure as in all Bardic poetics but it was dependent on the Back blues singer to get it on and make up on the spot all the rhymes and all the personal comments, all the moaning, empty bed samsara lamentations of the moment while singing. So that Tibetan poetics and American poetics are based on the spontaneous. The key to this is that you have to accept that the first thought is the best thought, you have to recognize that the mind is shapely. Because the mind has shape, what passes through the mind is the mind’s own, so that is all in one mind, it is all linked connectedness and consequence. Observe your mind rather than force it, you will always come up with something that links to previous thought force. It is a question of trusting your own mind finally and trusting your tongue to express the mind’s fast puppet… spitting forth intelligence without embarrassment.”

Ginsberg’s method may sound familiar to people who follow the work of Brakhage for instance, where his muse directs him through his work… I appreciate this link with the Muse but my background has directed me towards seeing it in a less individualised state. Through the 1990’s I have come to appreciate the way other people can contribute to my projects… that there is an energy around the making of a work that can create a more participatory model during the making… in other words, I get a lot of help from my loved ones, friends and assistants and I see them as part-makers of the film. Chance elements come into play when this kind of energy is set up around a project, and through people, these chance elements often help direct the film. The film is a tuning fork, resonating through people and events.

EDITING

Whereas the spontaneous is most connected to the shooting of films and is quite light and free the editing process has been tortuous, these collected concrete forms of memory do not always go together, and it can take a long time before I sculpt them into shape, blending story and form. Maybe this is why some of my films take five to seven years to complete.

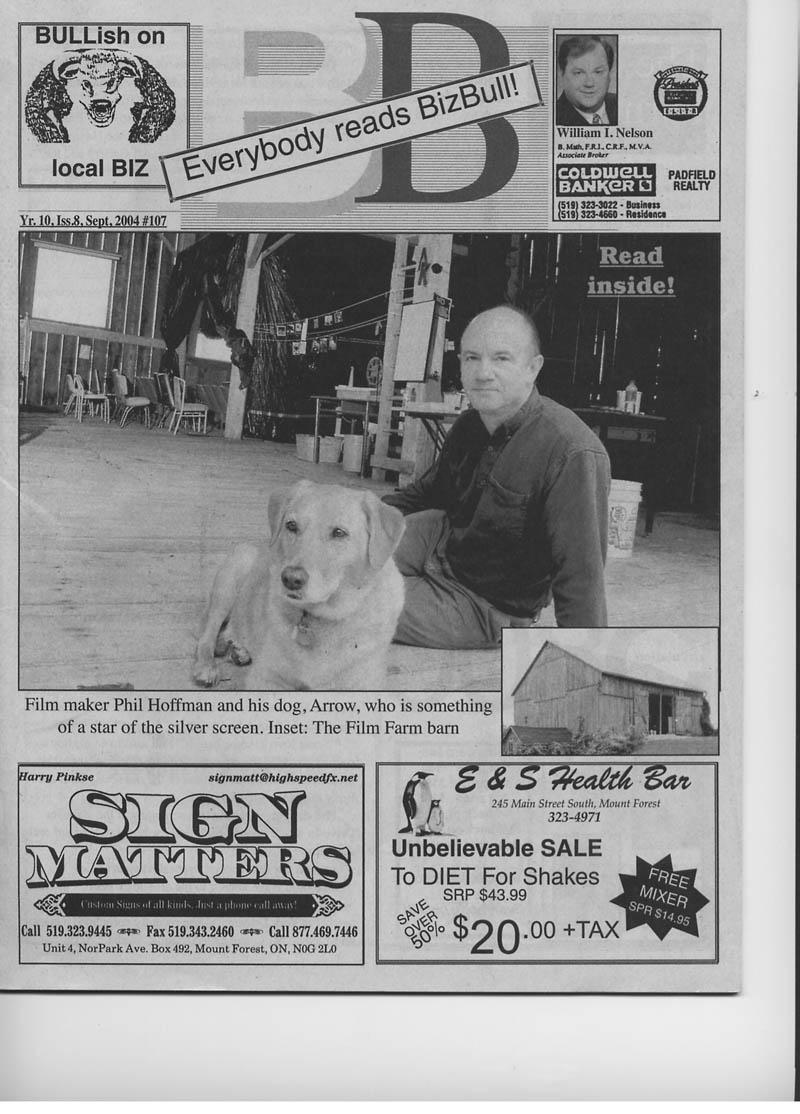

FILM FARM

This process-oriented approach to making was used when I and my late partner Marian McMahon set up a Filmmaking Retreat in 1994, in Mount Forest. Participants are urged to shoot without scripts, letting the camera’s confrontation with the world be the first place to start, rather than the written word …the camera meets the world. Since hand processing facilities are available, participants can shoot and re shoot, experiment with various photo-chemical processes and gradually films surface. My motto is, if you can write a poem in a day, you can make a film in a week. Participants do not need to necessarily come to the film farm with an idea… my sense is that there is a film in everyone which can be drawn out anywhere… The atmosphere created at the film farm by the assitants/teachers who help out every year, make it conducive to creative expression.

DIGITAL VS VIDEO

I am more interested in passing on a way of working than a medium(for example celluloid), in the so called digital age….

What these ashes wanted was finished on film but it makes use of high-8 and 3/4″ video, digital video, 16mm reversal, 16mm high contrast and negative, digital to film transfers and so on… It’s a way of working that I would be more concerned about losing during the corporate mandate of this millennium. Film has a beauty we should use when we need it, even if we have to get into making our own emulsion up at the film farm…

Helsinki Trip 2004

by Philip Hoffman

Once again I find myself in Finland, and wonder why I am drawn to this place. It isn’t only because I have good friends here from my many other visits. This is a place where I feel comfortable, and maybe the only place in my life that reminds me of my mother’s eastern European heritage. Of course, I know that Helsinki is as developed in city life as any Canadian city, yet somehow life is more the pace I can handle, compared to that of the busy North Americans cities. I know I’m romantically naive in these judgments, but I also know that our experience of the world is always filtered through our greatest passions, and the foundational moments. Babji (my mother’s mother) taught me how to shoot from the hip. When she took pictures, she did not look through the lens, but just kind of used her body to find the picture. This daily practice of acknowledging the body (and not only the mind), in my filmmaking, working the hand with the heart, telling stories that are both personal and, I hope, universal, finds its source in Babji’s kichen, where supper chats went on through the night, as light and dark tales of their past were laid out one by one on the kitchen table.

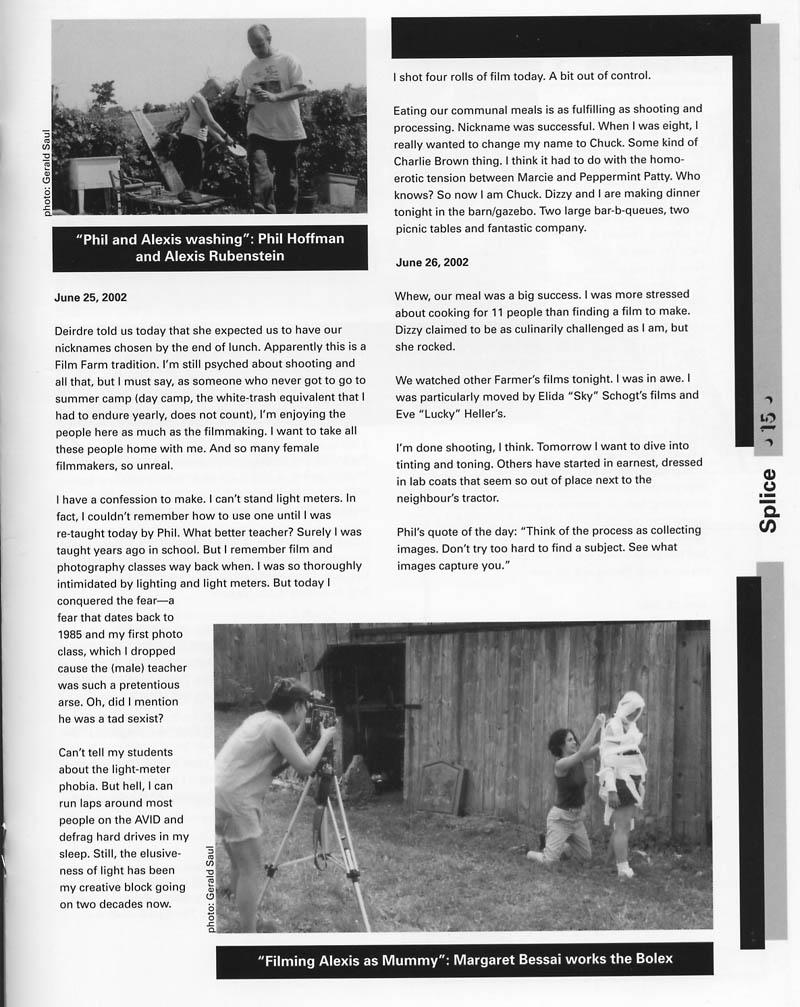

The Trip

Sami picks Janine and I up at the airport. I’ve come to do six days of workshop with Finnish filmmakers. Sami, who will be co-directing this venture, and Tuula who is hosting the workshop for her students at UIAH along with some students from the Art Academy, have organised everything just right. It is colder and darker than Canada. I look out the window and think about my friends back home who have gone to warm climates for their holidays.

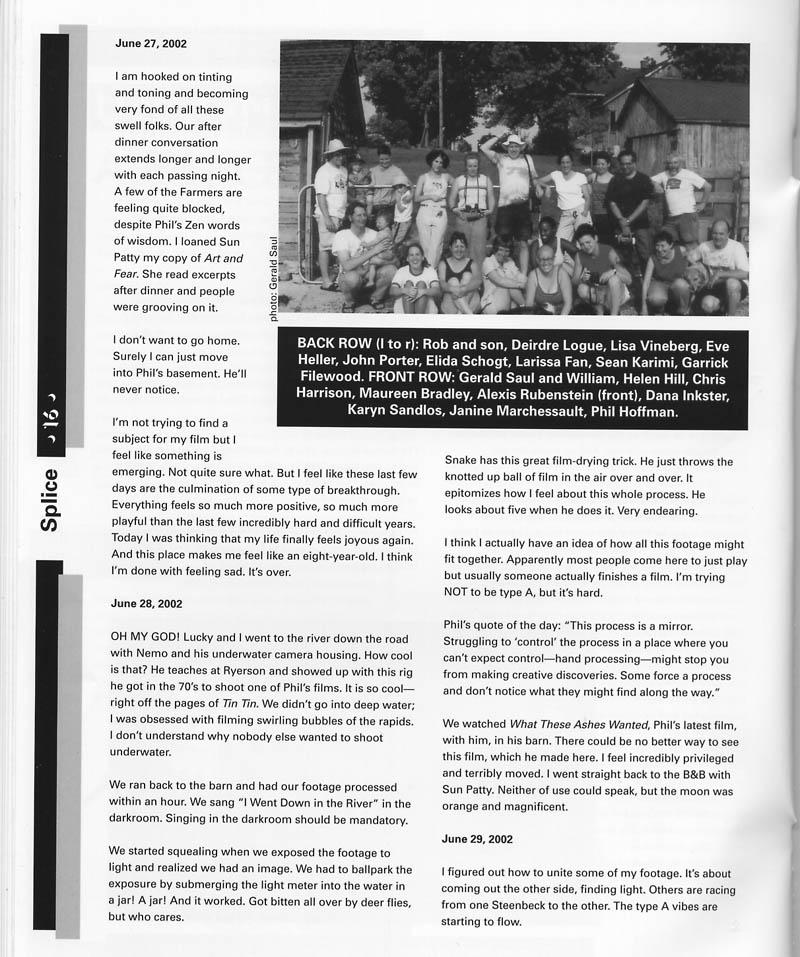

After a day of organising the workshop (it starts tomorrow) I decide to take Janine out to an old haunt. Elite. The wine and food are good. This is familiar. There is an open screening next door at a local gallery, so we slide over and during the film breaks, the old gang starts appearing before my eyes, one by one: Denise, Mikko, Oliver, Seppo, Ali, Sami… they are all continuing to make and screen their work locally and internationally. There is great energy in this little basement ‘open screening’ and the work covers the range of alternative practice from documentaries that skillfully deconstruct Finnish history to campy critiques. This reminds me of the old days of the Funnel experimental Film Theatre in Toronto where people show up not knowing what will be screened but always leave entertained, stimulated and yes, a little tipsy. What is great about it is that it’s a place to share an image, a work in progress or a brand new short, and have at times a deep exchange about some aspect. It is a place where old ideas and films get revamped and new ideas for films develop. It is polar-opposite to the ‘pitch,’ a process used nowadays in the commercial and independent film world which is less about development and the nurturing of an artistic practice and more about authoritative control through an industrial model. What I saw in the ‘Open Screening’ follows what Jonas Mekas meant when he called the New American Cinema movement, a living cinema. In that little basement screening no one talked about not enough funding for their project. I heard nothing about problems people were having trying to secure a producer, so they could make their film. There seemed to be no yearning for the most up-to-date digital tools. This kind of film and video is more akin to the Canadian artist, Joyce Weiland, who made films on her kitchen table. In her work the stuff of everyday life surfaced.

Before sleep I remember the words of a former teacher of mine, Rick Hancox. If the Romans made films, would we be most interested in seeing their feature films, or their home movies and personal films?

A bunch of nervous students, and a couple of nervous instructors find themselves in the same room, 9am at UIAH, on the first day of the workshop. Sami decides to put on the comical film …Mongoloid by American Avant Garde (comedian) filmmaker George Kuchar…and the ice is broken…..we come together in laughter. Many more films are screened. There is no shortage of questions and opinions regarding the work, once again dispelling the myth that the Finns do not talk (as I was told during my first workshops at ETL in 1989 -92…I can’t imagine Anu, Kiti, Petri, Arto, Sami, Heiki, Vesa not speaking!!!). Starting tomorrow the participants will bring in projects they are working on. Ones which they have had problems with. We will look at them together.

The projects screen one by one. People explain what they are trying to do. These projects are as deep and dark and as strongly felt, as anything I’ve seen, as anything in life. The most obvious problem surfaces time and time again. The form often does not fit the subject. Participants are forcing the passions of their life into conventional forms, handed down byHollywood…handed down by funding agencies…handed down by film schools. I understand this problem so well as I have been teaching within filmmaking institutions for years. So often, the curriculum cannot keep up with all of the needs of the students, of the industry, of the art form. At York University where I have been teaching for four years we finally decided to make a change to allow the possibility of developing innovative forms, yet maintaining the needs that students and the industry has to develop conventional narrative. In year three and four, students choose one of the following as a major: Fiction Project Workshop, Doc Project Workshop or Alternative Project Workshop. Alternative covers everything from innovative non-linear fiction to experimental projects to hybrids of Doc, Narrative and Experimental. When the decision to change the curriculum from one that favoured fiction filmmaking to one that allowed the possibilities of three genres, one of the Professors suggested that every year we would have trouble filling the alternative class. This past autumn, we discovered that this class was the most sought after, and the only one in which students were turned down due to over enrollment.

Days are filled with screenings, talking about films…getting to know the group, what they most would like to realise…the fears we all have about making work that pushes boundaries…how much? Is it enough? Too much for an audience, and not enough for the filmmaker is the usual answer from experimentalists.

The nights are filled with meeting old friends… Seppo takes me for a ride in his new ambulance…finally he has room for all his film projectors, cameras, films and videos. He tells me about a plan to use the speaker system for a poetry/film performance…he’s already got the projector rigged through the back window, and powered up. It’s good to hear what people are up to in work and life… Denise… Mikko…gathering their new projects to show at our Fabulous Festival of Fringe Film in Canada, where we screen films in rural Ontario during the month of August in galleries, town halls, against old barn walls, under the stars, and the grand finale at the Drive-In. I want to show Ilppo’s Routemaster there this summer …last year I ran his Plain Truth to the applause of horns honking exuberantly by the end. Sami’s Twone would look good, sprinkled throughout the program… it would be magnificent to have some Finnish visiting filmmakers. ..let’s keep the exchange going! As well, as it will be the 10th Anniversary of my Film Farm Workshop, a 35mm hand-processed group film will screen under the stars at the drive-in.

By the last day of the workshop it appears everyone has come some distance….Sami and I never really know how these kinds of creative workshops affect filmmaker’s work, but I like to think that they give participants confidence to go a bit further then they have already. I know it has worked that way for me. Workshops with Jean Pierre Lefebvre, theQuebequois narrative director, helped me understand that pushing narrative boundaries is as important and exciting as pushing boundaries in documentary and alternative film. During our mandatory pool game at the local hall, I realised the worth of these visits, how they have fueled my own filmmaking (the thankyous to Finns on the end credits of my latest film What these ashes wanted, is as long as your arm, and proves that). And the thankyous are mutual as the talks continue that night in the pool hall with Anu, Ilppo, Kiti, Toni,Juha, Sami, Passi…and much, much later an ecstatic Petri rolls in, plays me a few games, we’re the last ones left, and we talk about the first workshops in `89, the old times are always the good times …what is everyone doing.? Where’s Arto, Heikki, Monday is she still shooting? We talk it out to the cold Helsinki streets, and down to the railway station…

Originally published in AVEK (Magazine for Audio-Visual Culture), Finland, Feb. 16. 2004

Films and Fairy Dust

by Cara Morton

It started with this dream: I am surrounded by lowing cattle. The moon is pregnant, promising, full. The air is sweet and warm and I am on my back, floating in the grass, while Maya Deren pulls a tiny key from her mouth again and again, while Maya Deren pulls a tiny key from her mouth again and again, while Maya Deren … Kazaam! Hang on a second … this isn’t a dream at all. This is real. I am on a filmmaking retreat taught by Phil Hoffman on his enchanted property just outside Mount Forest, two blessed hours from Toronto.

I’m fully awake and it’s the end of the first day. Nine of us, eight women and one guy (“the guy on the girl’s trip”) have just spent an amazing day playing with the camera. For some it was a time for rediscovery; for others, it was that first glorious encounter between magician and medium, otherwise known as the Bolex. Now it’s around midnight, and we are lolling in the grass like the cattle in the field next to us, (chewing our cuds and watching Meshes of the Afternoon flicker off the outdoor cinema (the side of the barn). For me, this is film at its best: fields, forest, cattle, countryside and total immersion in the process of creation.

I went on the workshop in the first place because I hate film. I mean sometimes I have to wonder, what has gotten into me? Why am 1 putting myself through this agony? I’ve spent most of my grant money. I’m in the midst of editing and I find myself asking, what is this damn film about anyway? Why am 1 making it? What am I trying to say? At this point those of you who run screaming from process-oriented work can laugh at me. I don’t plan much (what do you mean, storyboard?). I like letting things happen, letting that creative, unconscious self reign. But sooner or later that insightful (not to mention delightful) self turns on me and I’m left stranded in a dark editing suite with the corpse of my film and that evil monster self who thinks analytically, worries about money and who just doesn’t get it! So, ’round about May, that’s where I found myself. But then, the cosmic wheel turned and I went on the workshop, hoping to exorcise this critical, anti-process, monster side of myself. And it actually worked. I opened up to my instincts, started trusting myself again. (So what if this sounds like a new-age self-help tirade. Just go with it …)

One of the first censors to go was the money-obsessed self-the self that abruptly grabs the camera away when you’re trying to have fun. Now, in the mainstream film world, this may sound subversive, or certainly weird, but if you can shoot without analyzing every detail, without worrying about money, money, money … Imagine! You can experiment! You can try things, be free with the stock! How? Cheap film! At Phil’s we were shooting the incredible Kodak 7378, at 12 bucks/100 feet. It’s cheap because it isn’t actually picture stock, but optical print stock. It’s black and white and has a varying ASA somewhere between twelve and thirty depending on how you process it. And it’s gorgeous: very high contrast with a fabulous dense grain.’

OK, so we can shoot cheap! But there’s more! Remember Polaroids? At the workshop it became clear to me that I had been missing that sense of wonder about film-that sense of playing an important role in a magical process. Thanks to Phil’s workshop I got that feeling back. How? Hand processing. It’s better than Polaroids because you can control the process of development. You can develop your film as negative or reversal, you can solarize (a personal fave), you can underdevelop, overdevelop-anything you want-in minutes. Imagine, you wander around the countryside shooting to your heart’s (and wallet’s) content and then run back to the barn, where the darkroom’s set up, and process your film. It’s hard to describe the feeling you get when you hang your film out to dry. It’s a mixture of wonder, accomplishment and connection to the medium. And all this for less than one quarter of what you usually pay.

At this point, you can tint or tone your film with other colours to get some far-out. moody effects. Most of us favoured the potassium permanganate, which eats away at the film emulsion.

This brings us to scratching. lmagine not only not worrying about scratches, but trying to make them! Nothing, I mean nothing, beats stomping on your film, rubbing it against trees, rolling around with it in the grass or even chewing on it like bubblegum (OK, no one actually tried that, but it would be fun, no?).

These experiences totally changed my relationship to film as a medium. I became equal to it; no, I became the master of it. No more God-like can of film handled with white kid gloves: I shot it and I can fuck with it, and if I don’t like it, well, I can re-shoot for the price of a new pack of crayons. Film can be a truly plastic medium.

Believe it or not, the mythical last day arrives. We have our final screening (most of us have actually finished a short piece) and then a discussion. Later that evening, as we are striking camp, the sun is miraculous, huge and orange, setting over the marsh. It’s so beautiful that we stare, but after five days of total immersion in beauty, we are saturated by it. It’s too much, all we can do is ridicule how goddamn perfect it all is.

On the way home I realize I’ve achieved more than I imagined possible. I’ve found the magic in film again. My next dream goes like this. I’m in Toronto, in a basement, surrounded by streaming ribbons of film I’ve shot and processed myself’. I start chewing on it. I chew and chew until my film turns into a tiny perfect key, until my film turns into a tiny perfect key, and I pull it from my mouth …

This article was first printed in the Liaison of Independent Filmmakers (LIFT) Newsletter. Summer 1996.

From Landscape with Shipwreck (Toronto: Insomniac Press/Images Festival, 2001)

Farming the Unconscious

The Independent Imaging Retreat

by Chris Gehman

(Curated by Chris Gehman • Hanover Civic Centre, 341 10th Street, Hanover • Saturday, Sept. 20, 2003, 8:00 pm)

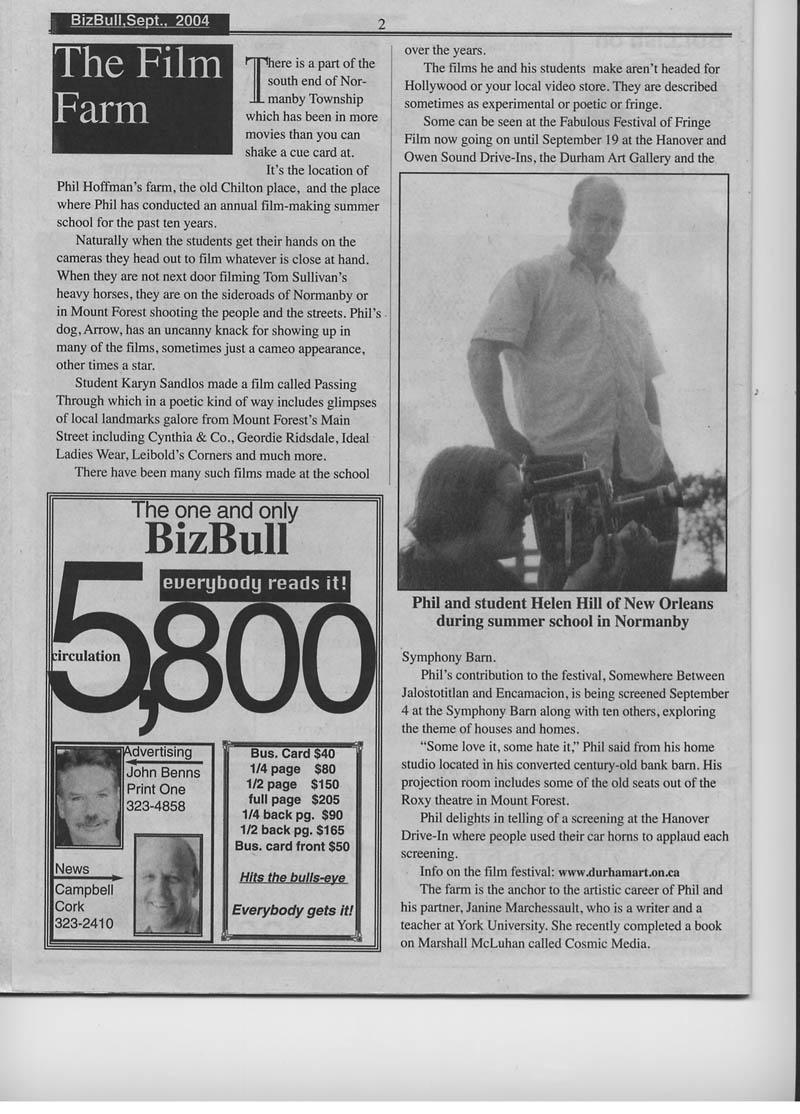

The Independent Imaging Retreat, now in its tenth year, was founded by Canadian filmmakers Philip Hoffman and Marian McMahon to encourage a direct, hands-on approach to filmmaking that is far removed from the costly, hierarchical and inaccessible industrial model, with its intensive division of labour into many specialized craft areas. Each summer it brings to Mount Forest, Ontario, a small group of interested filmmakers – some novices and some highly experienced – for an intensive week of shooting, processing, watching and editing, most of the action taking place in and around an old barn on Hoffman’s property.

The retreat is part of a little-recognized international movement towards what might be called an artisanal mode of filmmaking – one in which the artist works directly on every stage of a film, from shooting and editing to the processing and printing of the film stock itself. In the past, even the most solitary of avant-garde filmmakers have usually turned the processing, printing, and negative cutting of their films over to professional film laboratories whose primary products are commercial films, advertisements, television programs, etc. A new generation of filmmakers has emerged, willing to forego the predictability and standardization of industrial processes in favour of direct control of their materials, motivated by a combination of necessity and curiosity.

Economically, the existence of adventurous independent films has been dependent upon the existence of a larger commercial industry that creates a demand for products and services, and therefore keeps prices relatively low. As the commercial film industry, particularly its low-budget ranks, have shifted production away from 16mm film to digital media, the availability of 16mm film stocks and services such as processing and printing has declined, and will certainly continue to decline further.

There are several possible responses available to filmmakers who have been dependent upon this economy: follow the shifts in the larger industry and switch to video and digital media; transfer production to 35mm, with its higher attendant costs; or take control of those stages of the filmmaking process which are disappearing at the business level. (Of course, many artists will practice some combination of these basic strategies.) The Independent Imaging Retreat has played a crucial part in North America in developing and disseminating the basic skills and knowledge necessary for artists to begin taking control of those crucial elements of the filmmaking process that are becoming harder to find from commercial sources.

It would be a mistake, however, to look at the movement towards artisanal filmmaking as solely an economic response to outside factors. As is so often the case in art, internal aesthetic ideas and pressures produced effects that precede their putative economic causes: The movement was burgeoning well before the practical effects of the shifts in the commercial industry had begun to make themselves felt by independent filmmakers. The examples of individual filmmakers have been crucial in motivating new generations to take matters into their own hands: Internationally renowned artists such as Len Lye and Stan Brakhage offered inspiration in their lifelong commitments to individual, artisanal film practices. And in Canada, across a period from the mid-60s through the present, filmmakers such as Joyce Wieland, Al Razutis, Carl Brown, Gary Popovich, Barbara Sternberg, Philip Hoffman and Steven Woloshen have experimented in different ways with unconventional approaches to the film surface and image through processing, colour toning, optical printing, scratching and painting, etc.

What these filmmakers tend to share is a desire to complicate the reception of the image: In contrast to the ordinary commercial practice of creating seamless, transparent representations – illusions – through which stories are told, many independent filmmakers are committed to a more complex kind of image-making in which the projected image may be both representation and object simultaneously, or may reject representation altogether (as is the case in many of Stan Brakhage’s and Len Lye’s films). The filmmaker builds images, ideas, stories, atmospheres, while at the same time keeping the method of construction of the film, and the images which make it up, present in the viewer’sconsciousness. In this context, the nicks, scratches and inconsistencies in development which result when a roll of film is processed “spaghetti-style” in a plastic bucket are not seen as a problem – as they certainly would in making a commercial movie! – but become part of the film’s style and method.

Artists mining this cinematic vein tend also to embrace a process-oriented mode of production, in which the film’s form and subject are discovered in the course of the making, rather than following a preconceived script or plan – an art of discovery, then, not only of management and execution. This is what allows these artists to dispense with thepredictability of laboratory results, knowing that footage they hoped would be particularly good might not turn out as expected in the processing. It is a practice which embraces genuine experimentation and the discovery of a personal method of production.

Over the past ten years, more than 125 artists have attended the Independent Imaging Retreat. Its effect has been to share techniques and skills, but more importantly to encourage an approach to filmmaking which is as far removed as can be imagined from the conventional cinema whose products are so relentlessly promoted. A poetic, individual, exploratory filmmaking in which the artist is involved at every stage of the process. Perhaps for this reason, the Retreat has proved hospitable to people whose view of the world is poorly represented in the commercial media: women (there have been several weeks offered to women only), gay and lesbian people, people of colour and people from regions outside the recognized “cultural centres” of Canada and the US. This program provides a small sampling of the many films which have been made through, or under the immediate influence of, the Independent Imaging Retreat. Because the participants share basic materials and techniques during the week they are working together, there are often similarities in the surface appearances of the works; but each artist has gone on to apply these techniques and skills in a different way.

Chris Gehman is an independent filmmaker, film and video programmer and critic. He is currently the Artistic Director of the Images Festival in Toronto (www.imagesfestival.com).

PHIL’S FILM FARM

John Porter, Canada • 16mm b&w 10 min. 2002

Canada’s most prolific filmmaker, John Porter has made more than 300 short films, mostly in Super-8. He has also been documenting Toronto’s independent film scene in still photographs for about thirty years. This film brings these two practices together, creating a poetic document of the 2002 Retreat in which the filmmakers and the setting are laminated in gorgeous black-and-white in-camera multiple exposures. (The film may be shown either silent or with sound, depending upon the circumstances.)

MINUS

Chris Chong, Canada • 16mm b&w 3 min. 1999

Minus is a hand-processed, unedited stream of movements. After subtracting most of what took place before the camera, what isleft is remnants of light and rhythm, traces of a body in motion. This was Chong’s first 16mm film, and demonstrates the kinds of rich results that can be obtained from simple, highly restricted means and techniques.

HARDWOOD PROCESS

David Gatten, USA • 16mm colour silent 14 min. 1997

“A history of scarred surfaces, an inquiry, and an imagining: For the marks we see and the marks we make, for the languages we can read and for those we are trying to learn.Reproduced by hand on an old contact printer resulting in individual, unique release prints.” (David Gatten)

DANDELIONS

Dawn Wilkinson, Canada • 16mm b&w 9 min. 1997

“Lyrical and full of mirth, this filmmaker wonders out loud in her first film: How do I make myself at home in a landscape made foreign to me? Wilkinson looks at her self – black – and ponders in the white landscape called Canada how can she ‘enjoy the flowers’ as she cartwheels with great panache through fields of them. What kind of relationship to the land can she have in a place where she sees herself but where others constantly ask: Where are you from? Wilkinson’s existence vis-a-vis the land seems to lie somewhere in between the extreme long shots and the close ups that make up the film, giving at once the feelings of intimacy and estrangement.” (Marian McMahon)

SWELL

Carolynne Hew, Canada • 16mm b&w/colour 5 min. 1998

Carolynne Hew’s Swell extends the techniques used at the Retreat by reworking her film footage in the digital realm. The result is a layered, oceanic embodiment of physical energy and desire.

THE SHAPE OF THE GAZE

Ma’ia Cybelle Carpenter, USA 16mm colour 7 min. 2000

Chicago-based filmmaker Ma’ia Carpenter acknowledges the pioneering lesbian filmmaker Barbara Hammer as a great inspiration. The Shape of the Gaze is a sort of manifesto of radical queer filmmaking in which Carpenter implicates the viewer in the exchange of looks between the filmmaker and her “butch” subjects, disrupting the usual filmmakersubject-viewer triad through interventions in colour and film surface.

PASSING THROUGH

Karyn Sandlos, Canada • video 12 min. 1998

Since participating in the Retreat in 1998, Sandlos has been one of its main organizers most years, and has also co-edited a book, Landscape With Shipwreck, about the films of Philip Hoffman. Passing Through develops a more explicit narrative line than most of these films, creating a lovely journal of a short stay in a small, Ontario town during which nothing seems to fit properly.

GLINT

Eve Heller, USA • 16mm b&w silent 5 min. 2003

Shot in the Saugeen River using a special underwater housing, Glint is a film-poem of the utmost subtlety and finesse, in which images emerge from black only to vanish again…

Related programming: Be sure to see Deirdre Logue’s installation Enlightened Nonsense: 10 Short Performance Films About Repetition and Repetition, a film series shot over the course of several years at the Independent Imaging Retreat. This work is installed at the Durham Art Gallery from Aug. 21 to Sept. 28. Address: 251 George St., DurhamTelephone: 519.369.3692 • Web: www.durhamart.on.ca

Hours: Tuesday-Friday, 12-5; Saturday-Sunday, 1-4

The Film Farm

Interaction Through Navel Gazing: Philip Hoffman and First Person Cinema

PHILIP HOFFMAN: Canadian Independent Filmmaker Comes to Perth For Solo Screening!

Toronto based filmmaker Philip Hoffman has been making independent films for twenty years and his celebrated works have been seen by festival audiences around the world. Philip is coming to Australia to screen his latest work at the Sydney Film Festival in June and on the way he is stopping off in Perth to present a selection of his short films at the Film and Television Institute.

The films of Philip Hoffman cannot be situated within any specific genre of film making, instead we see a remarkable shift between styles that incorporate the home movie, the idiosyncratic documentary, and the formalist exploration of the permutations of sound and image. Hoffman’s cinema is an intensely subjective one, often employing an emotional voice-over to colour the residual traces of the lost and found seen in faded family snapshots, grainy archival 16mm and standard 8 memories. Other works share a lyrical thread in the mode of Stan Brakhage with their graphic and rhythmic effects that engage a viewers perception in a complex dialectical relationship between the techniques of cinema and the physiology and psychology of vision. The poetic intention running through many of Hoffman’s images, from the shadowy black and white portrait of a dying grandmother in passing through / torn formations to the ephemeral floating rhythm of a fragmentedcityscape in Chimera can be understood in part as a desire to reconstitute impressions of memory – (the filmmaker enters) “the work of making ghosts of the past for the future.” (SamLandels)

Denoting the family as source and stage of inspiration, Hoffman’s gracious archaeology is haunted by death, the absent centre in much of his diary practice a meditation on mortality and its representation. His restless navigation’s are invariably followed by months of tortuous editing as history is strained through its own image, recalling Derrida’s dictum thateverything begins with reproduction. Hoffman’s delicately enacted shaping of his own past is at once poetry, pastiche, and proclamation, a resounding affirmation of all that is well with independent cinema today. (Mike Hoolboom, Inside the Pleasure Dome: Fringe Film In Canada, 1997).

Program: river, passing through/torn formations, Kitchener-Berlin, Chimera

Special Matinee Screening attended by film maker Phillip Hoffman on Sunday May 31st, 1998, 5.30 pm at the Film and Television Institute, 92 Adelaide St. Fremantle.

Tickets $7 full or $5 conc/members. Please note change of date!

For all enquiries please contact Sam Landels on 9328 2808 or the FTI on 9335 1055.

This event is proudly sponsored by Imago Multimedia Centre and The Film and Television Institute.

Impure Cinemas: Hoffman in Context

Landscape with Shipwreck: First Person Cinema and the Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom and Sandlos Toronto: Insomniac Press, 2001

by Chris Gehman

At the beginning of cinema’s second century, it’s instructive to remember how recently proclamations of the “death of the avant-garde’* (or “experimental film,” or “fringe film”) were a staple for filmwatchers concerned with developments outside the realms of commercial and art-house production (e.g., Chicago Reader critic Fred Camper, and Village Voice critic J. Hoberman). This imminent demise was seen as arising from an exhaustion of creative possibilities, and, for Camper in particular, the domestication of a formerly independent and vital movement. In a 1989 statement, Camper wrote that

What began as an anarchic movement with a singular mission-that of changing the viewers’ sensibilities and thereby changing the world-is now a fragmented collection of “schools.” The phrases “avant-garde film” and “experimental film” no longer denote works that break new cinematic ground; rather, they name a style, almost a genre, which has its own set of defining characteristics. (32)

Towards the end of the 1980s this position seemed to solidify into a consensus, and filmmakers too joined the chorus. Australia’s Arthur and Corinne Cantrill, for example, toured with a film performance in which they called themselves “the last filmmakers,” and Jean-Luc Godard’s television series Histoire(s) du cinema was markedly elegiac in tone. Among many artists who shifted their production mostly or entirely away from film (Jordan Belson, Malcolm Le Grice, AI Razutis), American independent Jon Jost “defected” to digital video-and to Europe. There he became an outspoken critic of what he sees as an irrational fetishization of the medium and a hypocritical institutional/critical environment surrounding experimental film.

During the late 80s and early 90s there were genuine signs that experimental film was in trouble. To begin with, many influential independent filmmakers have died over the past two decades. These include Andy Warhol, Hollis Frampton, Paul Sharits, Marjorie Keller, Harry Smith, Warren Sonhert, Joyce Wieland, Sidney Peterson, and Kurt Kren. From the mid-80s through the early 90s, most of the institutions that supported artists’ work in film, among them Anthology Film Archives and the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, the Canadian Film-makers Distribution Centre, the London Filmmakers Coop and Canyon Cinema, experienced crises caused by fractures and antagonism between different factions. Thesecrises were exacerbated by dwindling state support and often haphazard administrative practices. In Toronto, the 1989 International Experimental Film Congress, which was organized partly to respond to the idea that experimental film was no longer a vital force, became the site and the subject of heated debates that broke down roughly along generational lines. A younger, more politically oriented group of artists, theorists and programmers attacked what they saw as an outmoded and elitist conception of the “avant-garde,” particularly a purist formalism, that had dominated experimental film production and deformed its discourse. Further, some major art galleries (such as the National Gallery of Canada and Art Gallery of Ontario) appear to have dropped film programming and acquisition from their regular activities, while others have cut them back to almost nothing. Acquisitions of film prints by libraries and educational institutions, once a small but important source of income for at least the better-known filmmakers, have all but ceased and a revival of the practice seems very unlikely. And it is probably true that an increasingly academic environment made for a less vital film culture, at least for a particular segment of the field, and for a particular period of time.

But experimental film did not die. Many of the key institutions mentioned above have recovered their stability over the past several years, and new venues for the exhibition of artists’ film have sprung up. Sonic of these have been shortlived, while others have settled in for a long life. Critical writing on film is almost completely absent from general-interest art journals and magazines, but there are specialized journals that publish serious writing on film. A heartening range of books has appeared over the past several years, including Scott MacDonald’s three-volume collection of interviews with filmmakers, A Critical Cinema. Ultimately, however, it can only be the healthy, prickly condition of filmmaking itself that proves these proclamations of death to have been premature. What threatens the form now is less a matter of creative exhaustion than the possibility that the basic tools, materials and services needed to complete a film may disappear as the commercial industry turns entirely towards digital media.

What has perhaps passed away is a certain image of the artist as romantic, visionary hero, and an allegiance to large-scale, often highly purist, abstract models of making. Some very interesting film artists of the past two decades (e.g., Jennifer Reeves, Philip Hoffman) have moved between styles and genres in a way that might have seemed confusing or incoherent to an earlier generation.

The characteristic elements of these films are likely to be philosophical, thematic, and personal, unlike the formal “signature style” or clear progression of artistic development that made up the work of respectable artists in earlier decades.

There has, then, been a significant shift since the “heroic” period of the avant-garde that found its critical spokesman in P. Adams Sitney, and its bible in Visionary Film: The American Avant-garde 1943-1978 (second edition 1979). This book became a flash point for much of the debate over the canonization of experimental film. Jason Boughtonsummarizes the critical point of view:

[Sitney’s] book acts and continues to be used as a lexicon of alternative filmmaking practice, not only for the years it claims, but more generally, forward and backwards in history. Like all written history it is not just a locus of memory but also a kind of sleep capsule axis of active, official forgetting … The problem is the form history comes in [in] Visionary Film-the confusion of memory and forgetting, the thinly veiled claims of completeness and simple reportage. When one speaks of the Avant-Garde, is it just one era, a single group of friends, great men, a unified field that is referred to? Is avant-garde anidea or an identity? Is it (lead, and if not, can we finally let it die, and take with it a back-breaking debt to every other logocentric, exclusionary Avant-Garde…? (7)

Boughton quarrels with Sitney’s tendency to categorize makers and their works according to major art-historical movements, and takes issue with the staunchly apolitical nature of Sitney’s analysis. He accuses Sitney, for example, of ignoring the radical socialism of Ken Jacobs in his discussion of Jacobs’s works. Boughton points out that Maya Deren is the only woman filmmaker given serious consideration in Visionary Film, while Marie Menken is treated primarily as an influence on male filmmakers, and as the wife of Willard Maas. Boughton concludes that “[t]he exclusion of politics in Visionary Film would almost be comforting, an easy resting place, were its politics not so visibly exclusionary” (6).

The “death” that the critics of the 80s predicted, then, was perhaps not the death of the experimental film per se, but rather the death of Sitney’s particular “avant-garde:’ Since that time we have seen a general cultural shift, in which the coherent psychological, spiritual and sexual identity of the individual allegedly asserted by the Romantic tradition and examined by Sitney has been replaced by a conception of the individual as a collection of interrelated aspects under the influence of an array of social, cultural, and political forces. This shift manifests itself in film in several ways: through an explicit examination of personal and family histories: through an interest in the social construction of gender, race, and ethnic identities; through a desire to convey journalistic or documentary content without resorting to discredited concepts of neutrality or objectivity; through a renewed use of “staging,” that is. the performance of roles and scenarios, though without an attempt at the kind of realism that characterizes the mainstream dramatic film; through the use of language as an integral communicative element; through the recombination of found/appropriated materials in films made using existing film footage, photographs, consumer objects, etc.; through the live “film performance;’ which challenges the idea of film as a mechanical medium of mass reproduction; and through a burgeoning interest in manipulating the chemical surface of the image.

In short, it is a certain purism of purpose and of form that has been given up by the new generations, but not necessarily a desire to see changes in the world. The development of self-financing, underground “microcinemas,” where a good deal of the material shown has both an activist and an experimental character. testifies to the continuing role of film as an art that aims to contest and to challenge social, political, economic and aesthetic hierarchies, as well as conventions of vision and representation. If anything, it is the members of the avant-garde that Fred Camper so fondly remembers who have found their way into the security of academe, while their contemporary counterparts, practising a myriad of hybrid forms, continue to struggle in a social and artistic environment hostile to film art. Yet the degree to which experimental film has not been accepted into the art world as an equal and crucial form, despite its overwhelming cultural importance over the past century. suggests that there continues to be something “indigestible” about the work, something which resists commodification and academicization. As the very idea of a unifying, central identity disappears. the pathways taken by filmmakers become ever more labyrinthine and far-flung, so that the job of the would-be taxonomist becomes difficult, perhaps even impossible. My aim below, then, is to account for some of the disparate elements of contemporary experimental film. creating loose categories that are subject to cross-pollination.

FOUND IMAGES

Critique is implicit in most contemporary found-footage films, and in films which appropriate images through related forms such as collage animation. Recently, we have seen the emergence of the experimental film “remake.” Jill Codmillow’s What Farocki Taught (I998), a remake of Harun Farocki’s Inextinguishable Fire (1969), and Elizabeth Subrin’sShulie, a remake of a 60s documentary about the young feminist Shularnith Firestone, are the best known examples. Implicit it most contemporary found-footage films is a challenge to conventional codes of representation and the social, political and sexual norms that are seen to he supported by those codes. This political intent distinguishes contemporary uses of found footage from the more poetic, symbolic, or formal uses by film artists who began their work in earlier decades (eg.. Joseph Cornell, Bruce Conner).

In tiny units of a few frames each, Austrian filmmaker Martin Arnold reworks scenes from Hollywood movies, which he has defined as “a cinema of repression and denial”(Address). Arnold’s work emphasizes the mechanical rhythm of the projected image and hearkens hack to the idea of cinema as a machine for the analysis of motion. Arnold’s films may be the fulfillment of Ilugo Musterberg’s 1915 essay describing the possibilities of reordering photographed motion in small groups of frames in order to discover a new rhythm impossible in nature. For Arnold. however, the cinematic machine is primarily an ideological apparatus, and he retools this apparatus in order to draw out every drop of meaning latent in the original material. Arnold’s Passage (I EActe (1993) reworks a scene of several seconds’ length from 7o Kill a Mockingbird (1992), extending it to 12 minutes by repeating every few frames several times. Leaving the original synchronized sound intact, he slowly allows the scene to progress. The effect is vehement, even violent, and creates a portrait of patriarchal family life and racial division from a scene that would pass almost unnoticed in its original context. The actors arc transformed into twitching puppets in the throes of an ideological seizure.

Like Martin Arnold. American filmmaker jay Rosenblatt has a background in psychology, and mounts his critique as a sort of diagnosis of symptoms. Rosenblatt uses found footage for the creation of compact. personal essays on subjects ranging from the construction of masculine identity in childhood (The Smell of Burning Ants. 1994) to theidiosyncracies of the 20th century’s great dictators (Human Remains, 1998) and the historical conflicts between Christians and Jews (King of the Jews, 2000). While Rosenblatt’s deployment of found images may seem relatively straightforward, functioning as illustration to an argument given in voice-over or titles, he often inverts the images’ values, finding sadness, pain and longing in grandiose, aggressive or blustery gestures. In many instances, Rosenblatt isolates and extends brief moments through optical printing, finding in them a nexus of meaning. In The Smell of Burning Ants, for example, two boys bouncing up and down on a car seat suddenly look at one another, and this look is extended to emphasize the underlying homoerotic subtext of their shared activity.

Craig Baldwin also uses found footage as a way to mount a critical essay, though his tone is less sombre and his thinking more lateral than Rosenblatt’s. In his instant classicTribulation 99: Alien Anomolies Under America (1991), Baldwin orders the film using a system of substitution: a race of alien invaders called Quetzals stands in for Latin American democratic and communist movements, while historical figures are represented by characters from sundry Hollywood movies (e.g., Blacula as Maurice Bishop). The film’s text as a whole, which takes the form of a demented, paranoid, right-wing rant about an alien conspiracy stands in for its opposite: a factual critique of American intervention against leftist movements in Latin America. Filmmaker Craig Baldwin is replaced by his rightwing equivalent, “retired Air Force Colonel Craig Baldwin.” The diversity of Baldwin’s source material and his style of optical printing tend to emphasize the material differences from one shot to the next. Baldwin mixes black-and-white footage with colour and documentary, or educational sources with dramatic sources. Much of the footage is worn, scratched and colour-shifted, so that the seams are emphasized and the result continually reminds the viewer that the film has been “stitched” together, like a patchwork quilt, or Frankenstein’s monster.

The use of found footage can extend to the presentation of intact fragments with minimal alteration. For instance, Peggy Ahwesh’s The Color of Lore (1994) is presented almost in the same form it was found. Ahwesh has simply made an optical print of the found material and added music. Remarkably, this piece, a fragment of pornography beautifully decaying into organic clumps of colour, fits perfectly into the body of her work. The scene shows two women engaging in sex play over the dead, castrated body of a man, a violent conception of an anti-patriarchal lesbian order. Many of Ahwesh’s other films deal with women’s relationships in the absence of men, and particularly with moments in which acting cannot be distinguished from “authentic” or unstaged behaviour. Ken Jacobs’ Perfect Movie (1986) is another noteworthy example of the use of unaltered found images. The film consists entirely of unused 196.5 news footage on the assassination of Malcolm X, with its original sync sound intact.

In contrast, animators and collage artists such as .lanie Geiser, Lewis Klahr and Martha Colburn work frame by frame with manufactured objects and images cut from magazines and books, using these as “puppets”” of autobiographical or ideological reconstruction in a sense analogous to Martin Arnold’s refashioning of Hollywood actors into puppets of the cinematic apparatus. Where Geiser and Klahr tend to conjure lambent dream worlds that evoke the thoughts of a child confronted with a world it cannot understand, or the reveries of an addled adult in the grip of a fever or hallucination of nostalgia, Colburn’s animated collages proceed at a manic pace, wringing out perverse combinations of animal, vegetable and sexual images from her source material. Colburn uses pictures from slick magazines, especially pornographic and animal images, in brief and briskly paced films with a distinctly “pop” rhythm and distinctly “anti-pop” production values and morals.

THE DOCUMENTARY IMPULSE

One of the fundamental tenets of high modernism was that a work of art be a self contained object, independent of real-world referents. This idea has arisen in many guises. but for experimental film there are two main forms: the Structuralist/Materialist, and the Formalist. The Structuralist/Materialist argument (distinctly different from Sitney’s concept of “Structural” film) turns primarily on the issue of presentation vs. representation. The argument attacks as reactionary any film that relies on illusion for its process of meaning formation. Peter Gidal, probably the most insistent proponent of this position, wrote in 1974:

Structural/Materialist film attempts to be anti-illusionist. The process of the film’s making deals with devices that result in demystification or attempted demystification of the film process … An avant-garde film defined by its development towards increased materialism and materialist function does not represent, or document, anything … The dialectic of the film is established in that space of tension between materialist flatness, grain, light, movement, and the supposed reality that is represented. Consequently a continual attempt to destroy the illusion is necessary. (1)

In Gidal’s conception, documentation and narrative content presume a passive viewer, and most experimental films, including many abstract works, are understood to include some undesirable form of representation. Of the films that make up Sitney’s “Structural film” canon (those by Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, Ernie Gehr, et al.), Gidal writes of how “the discovery of shape (fetishizing shape or system) may become the theme, in fact, the narrative of the film” (1). For all the revolutionary intentions of filmmakers and theorists like Gidal these ideas, and the extremely circumscribed possibilities available to filmmakers working within their boundaries, quickly begin to seem like a form of Marxistpuritanism: no dancing, music, or representation allowed.

The Formalist stream of filmmaking has tended to be less hound by strict rules and formulae, but it shares a generally anti-representational bent with Structuralist/Materialist cinema. In Formalist discourse on film, analogies with music abound. The idea is that film, like music, can engage the audience most intensely when it does not refer to anything outside its own formal system, when it does not rely on representation for its meaning or effect. The conception of film as a kind of “visual music” arose early in the century, and remains an active model for filmmakers such as Stan Brakhage, whose non-representational films attempt to embody a type of “pre-linguistic” vision.

If a disavowal of representation was a defining feature of a great deal of experimental filmmaking up to about the mid-70s. a major shift in the postmodern period has been the emergence of a generation of artists whose work engages with a specific “extra-filmic” content. However, these artists are not naive about questions of representation, nor do they subscribe to any particular school (e.g., cinema verité/direct cinema) that asserts the possibility of a “neutral” or “objective” representation. Rather, there is a general awareness that every work is a construction, an argument, whose formal elements and representational content together constitute the substance of the argument. In a sense, these artists haveexpanded the interest of many structural filmmakers from strictly visual or aural perception to include questions of social, sexual, and political perception. This process demands that the artist foreground the mechanisms by which meaning in a film is constructed, so that traditional documentary techniques (the sync-sound interview or “talking head,” for example) are generally avoided in favour of a clearly constructivist approach that may combine voice-over, titles, original and found footage.

In keeping with this awareness, many artists choose to focus their documentary explorations on those subjects closest to them: for instance, their family histories or their sexual, racial, ethnic or religious identities. Su Friedrich maintains a rigorous intellectual distance in excavating her childhood memories in Sink or Swim (1O’H)). ordering the material according to an arbitrary system akin to those often employed by structural filmmakers-the alphabet in reverse (beginning with z for zygote). Elida Schogt, in Zyklon Portraituses a similar distancing technique for her elegiac account of the death of her grandparents during the Holocaust, arranging archival footage, home movies and hand-painted film into two parallel narrative strands. The first recounts Schogt’s Jewish grandparents’ lives in the words of Schogt’s mother; the second describes the development of Zyklon B gas, first as an insecticide, then as the means by which concentration camp prisoners were murdered in vast numbers by the Nazis, the description presented in a neutral tone reminiscent of the conventional documentary. The history of a chemical and the history of Schogt’s ancestors inexorably converge in the gas chambers of Auschwitz.

Other artists use the documentary form to question the “truth value” of the image. Jesse Lerner’s Ruins (1998) uses the strategy of deliberate and announced falsification to call into question Anglo-European interpretations of preColumbian societies such as the Mayan, Aztec and Toltec. Combining found footage with (presumably) scripted interviews, footage shot to look like found footage, etc., Lerner explicitly addresses the difficulty of distinguishing between the “authentic” and the fake, including a brief quote from OrsonWelles’ F 1 ,or hake (1973). The film also deals with the problem of authenticating pre-Columbian artifacts when the museums are full of fakes and replicas that stand in for “real” artifacts. William Jones’ Massillon (19)1) combines social landscape photography similar to that of James Benning with personal history (his experiences as a gay youth in a homophobic Midwestern environment) and social history (tracing the development of legal constraints on homosexual behaviour). In the film’s final section, these elements are drawn together in a visual and verbal portrait of a new California suburb. Jones’ method emphasizes the condition of the unseen, and the need to go beyond pure vision, by slowly “filling” his images with verbal information, so that the film’s blank and undistinguished locations become inextricably linked to the history and attitudes of the (unseen) people who inhabit them.

At no other time in cinematic history have so many artists been working directly with the chemical surface of the image, using a multiplicity of techniques: hand processing, colourtoning and arcane chemical treatments; homemade emulsions; application of paints, inks and dyes; scratching, abrading, and applying various materials to the film surface;collaging of cut-up pieces of film; and organic decay processes. A direct approach to the film surface is not new, having many precedents in avant-garde practice (e.g., Man Ray’s inclusion of strips of “rayograph” film in his 1923 Retour a la Raison, or Stan Brakhage’s 1955 Reflections on Black, in which the protagonist’s eye-images have been scratched away). Beginning as early as the 1930s-40s there are also examples from experimental animation in the cameraless films of Len Lye, Norman McLaren and Harry Smith. However.partly for economic reasons, but largely because of the enthusiastic interest of a new generation of makers, the sheer amount of this kind of work has vastly increased over the past decade.

Unlike Brakhage, whose cameraless hand-painted and etched films are intended to express an inner reality, a spiritual energy (he could be considered the most prolific abstract expressionist ever), many of these artists emphasize the material of the image in order not only to defeat its illusory qualities. but to draw attention to the physical presence of the film strip in the actual immediate space of the screening room, a concern that derives in part from the earlier Materialist discourse discussed above. This critical intention is confirmed by the frequent use of found footage as a source material for assorted physical alterations. The attack on the chemical surface of the film is implicitly an attack on the intended meanin(, of the original source images and on the “transparency” of conventional photographic reproduction.

In Germany, in films such as Jurgen Reble’s Zillertal (1989), and the Schmelzdahin collective’s Stadt Im Flamen (1984), artists subject films to organic decay processes and chemical treatments that create swarming masses of colour, often rendering the original images printed on the film barely legible. The sensory appeal of these films is considerable, given their highly textured and often brilliantly coloured surfaces, but the idea is as much to criticize the meaning of their source material as to provide visual pleasure. Stadt im Flamen (City in Flames), for example, humorously exaggerates the source “text” to the breaking point. Here, the filmmakers work from a super-8 print of a disaster film about an uncontrolled urban fire along the lines of The Towering Inferno. By burying the film underground for an extended period, colonies of mould and bacteria developed. drawing the pigments in the emulsion into new forms, often intensifying the colours. Under the influence of these processes, the system of representation breaks down, falls into disaster like the crashing buildings and fleeing citizens in the original film’s story.

The Armenian-Canadian filmmaker Gariné Torossian also works directly with the film surface, but in a manner more closely related to Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses (19e4-hH) than to the chemical approaches described above. Torossian chops her films up, dyes them, scratches and tattoos them, and tapes them hack together in new configurations, mixing super-8 and 16mm footage at will. Often this footage is already refilmed from a video image of an artwork or photograph, so that the number of generations of remove from any real-world referent is multiplied irretrievably. This becomes especially poignant in Girl From Moush (1993), a brief, haunting poem in which Torossian’s longed-for homeland ofArmenia is seen only in borrowed images that have inhabited and fermented in the artist’s mind.

FIIM PERFORMANCE

Some artists working in film reject its status as an impersonal, mass-reproducible object, mounting live film performances. These works partake of the film projection not as “text,” but as event. In these performances it is not enough to run industrially reproduced materials through a projector. The presence of the living artist is required, as in the performance of a piece of music, with the film and the projector as instruments to be played. Prolific Toronto super-8 filmmaker John Porter, in his ongoing Scanning series, uses the entire theatre as a screen, moving the projector by hand to create magical illusionist effects which simultaneously make the spectator acutely aware of the theatre space. San Francisco artist Luis Recoder creates cinematic paradoxes and time loops using found footage by the simple expedient of looping a piece of film so that it runs through the projector twice, allowing images from one section of the film strip to overlap with those from a later section. His Moebius Strip (1900) uses documentation of sports events: we see a racing car tearing down a track from left to right, the camera panning with it, and simultaneously, the same car racing from right to left. The result is one of frenzied motion that cancels itself out. Recoder’s Magenta (1997) uses a badly colour-shifted medical film demonstrating the proper methods for bandaging. Again, by running the same film through the. projectortwice, a visual echo is developed in which each action overlaps upon and repeats itself’. The sensation is created of a continuous caress in the context of medical damage, a feeling both soothing and disturbing.

PHILIP HOFFMAN IN CONTEXT

Philip Hoffman’s highly diverse body of work in film, beginning with On The Pond (1978), shares many interests and approaches with the work discussed here, but is distinct in its relation to the documentary tradition (which is of particular importance in the Canadian context) 1, and in its concern with personal and family history. From On The Pond toDestroying Angel (1998), Hoffman has balanced an awareness of film as a constructed object with a desire to explore specific extrafilmic themes. This has led him to a complex, first-person cinema very different from the formal approach of an earlier generation. When Stan Brakhage films his family in his famous Window Water Baby Moving (1959), or inScenes From Under Childhood (1967-70), the viewer does not learn the names of the people shown, does not hear their voices and discovers nothing of their past. The effect is two-fold: on the one hand, unencumbered by language, the film is able to hold in its form the very specific moments and energy of a particular time with particular people. On the other hand, everything is universalized: the children become all children and represent a state of “childness”; a birth becomes every birth, a symbol for all generations.

In Hoffman’s work the drive is very different and this leads to the inclusion of names and places, and the tracing of specific relationships. However, Hoffman’s acute awareness that the medium is never a neutral carrier of information leads to a variety of representational approaches, which often contain contradictory cues about the “truth value” of the material (see for example ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film (1986)). Alternatively, in a manner analogous to Craig Baldwin’s indirect treatment of his subject in Tribulation 99,Hoffman’s “absent presences” refuse explicit visual representation of their subjects. For example, both ?O,Zoo! and Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) have at their centres the story of a death, and in neither case is the dead person or animal represented visually. In varying proportions, Hoffman’s films play documentary content against fiction within a complex and shifting formal treatment.

Hoffman engages in an intense process of self-examination that is also an exploration of the capacities of his medium. In finding an appropriate form for his themes and ideas, Hoffman has developed a multiplicity of styles. But these are not arbitrary exercises; in each case, Hoffman demands of a film that it communicate certain crucial ideas to the viewer while promoting an intense awareness of the film’s means of construction. It is ultimately this foregrounding of the means of construction and Hoffman’s casual hybridity of genre, balancing the concerns of documentary, fiction and formal experimentation, that mark Hoffman as a filmmaker allied with the impurities of contemporary practice and engaged in a critical dialogue with the “straight” documentary tradition that has been so important in the Canadian context.

Hoffman’s influence as a teacher at Sheridan College and York University has been as important as his artistic influence. For example, although Hoffman’s films evidence a relatively gentle engagement with the chemically altered image, the summer film retreat he founded with his late partner Marian at their rural Mount Forest home has been inspirational to scores of young makers by teaching the basics of first-person hand processing and other chemical treatments of the film surface. This workshop has been a key catalyst in the explosion of first-person, hand-processed, cameraless and chemically-worked films in North America over the past several years.

The balance of interests in Hoffman’s work has shifted markedly from film to film. Much of his work enters into the relationship between documentary, fiction, and formal experimentation described here, while some of his films favour more generally formal visual and aural approaches (e.g., Chimera, 1992-3), and still others venture into aleatoricconstruction (Technilogic Ordering and Opening Series, 1992 ongoing project). In Opening Series, Hoffman gathers together several separate rolls of film, packaging each in its own box with an unrelated image or text on the outside. Audience members are asked to change the order of the boxes as they enter the theatre prior to the screening. Hoffman splices the film together in the order arrived at by the collective choices of the audience members; the film will therefore be projected in a different edit at every screening, moving his work into the realm of “film performance.”

The richness and complexity of Hoffman’s greatest works, which include passing through/torn formations, Kitchener-Berlin and ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film),have made him one of the important experimental filmmakers of the past twenty years. The insistent hybridity of Hoffman’s practice also marks him as distinctly postmodern, and his particular relation to the documentary tradition as distinctly Canadian. To assert that experimental film is no longer a living force is to ignore the challenge offered by Hoffman’s films and those of many other active filmmakers. If an earlier generation found its identity through a purity of form and identity, the strength of today’s experimental filmmakers may lie in a canny “impurism” that allows them to traverse the boundaries that separate documentary from fiction, abstraction from representation, and political from personal.

WORKS CITED

address. Pleasure Dome screening. Toronto, 18 Feb. 2000.Boughton. Jason. “Laid to Rest: Where the Forward Guard, and Their Regrettable Victory, Are Finally Dismissed.” Pinhole Cinema Project. n.p. 911 Media Arts Centre, 1993.5-7. Camper, Fred. International Experimental Film Congress. Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 1989.

Gidal, Peter. “Theory and Definition of Structural/Materialist Film’ Structural Film Anthology. Ed. Peter Gidal. London: British Film Institute. 1978.

1-2 Originally published in Landscape with Shipwreck: First Person Cinema and the Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom and Sandlos Toronto: Insomniac Press, 2001.