by Philip Hoffman

What does it mean for me and my work to have been in this place, Toronto?

Looking back over my film work of the past ten years, I see few traces of the city I choose as home… I notice my journal entries laden with references of people and places of the past.

August 19, 1979 – left Kitchener-Waterloo for the Toronto airport but first, goodbye to Mom and Babji, lying side by side. Babji speaks to me in her Polish, “Nie rozumiem…,” then, “I was think you were from the other place.” The old country is still with her, in her morning dream… to our dreams she taught us to listen… Though my work in film always deals with place, I find it odd that the place where I live and work is near-absent in my films… I question to what degree the present place where I am affects the output of the work.

January 1977 – I’m on a great flat houseboat, like the one old Roy Girdler used to ride on Lake McCullough, picking up cottagers on trips around the lake… I sit on the flat deck amidst people’s frantic legs. I’m six—I write everything down in my black book.

When have I turned the camera on Toronto?

In Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984), a storefront, John’s Religious Painting, Bloor and Bathurst, a glimpse through the window, through the wall, an artist copies a painting of Christ, the paintbrush careful to match the lines of the original, the camera careful, superimposing the image of the artist, a reflection on glass… Again from the same street, the same film, a procession up Bathurst Street, the Feast of Fatima, a questioning angel amongst many leaves her procession to smile for the camera. Mary is lifted up high, mingling with second-floor and third-floor rental flats. It’s an unusual day in the streets of Toronto when the grinding streetcars of commerce are replaced.

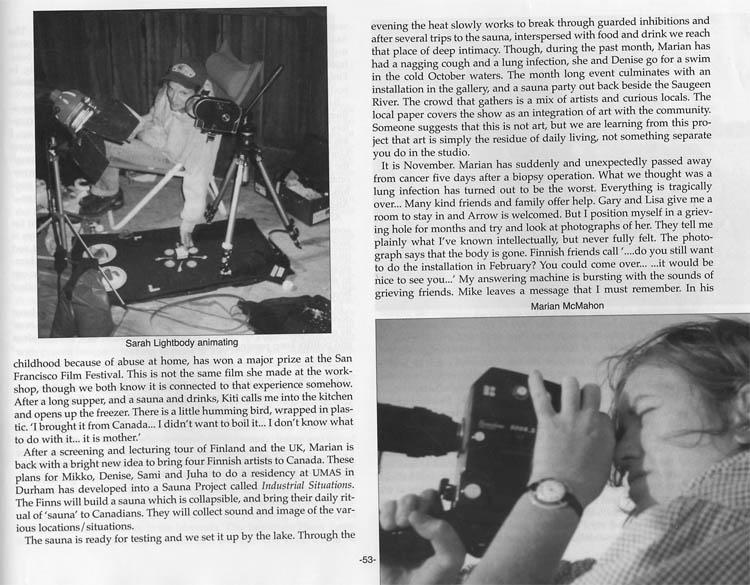

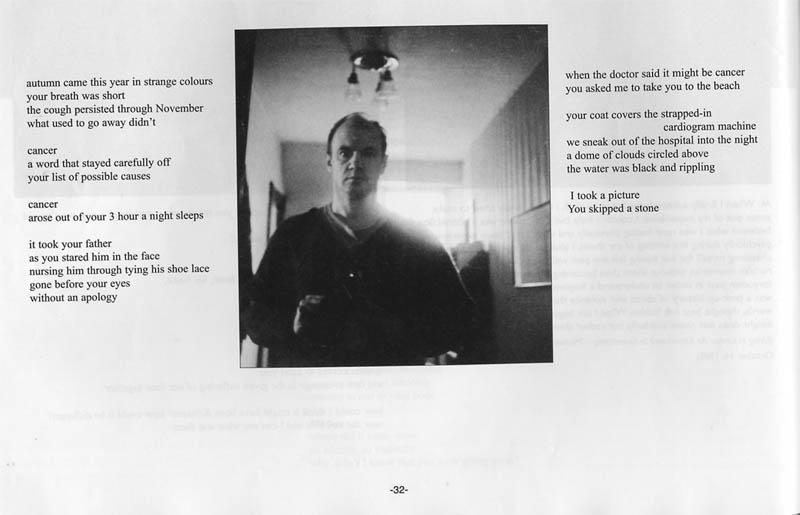

Near the end of The Road Ended at the Beach (1983), the basement on Bathurst Street is shown for a few seconds, with me, slumped over a light table editing film. At the time it seemed necessary to put myself in frame, fingers on film, trying to put an order to and make some sense of the seven years of collected film images… I learned about time, cutting film in that damp brick basement.

January 8, 1978 – I drive away from Toronto, the 401 again, passing through frozen fields, the harsh light cuts through the windshield, stops time on the road. On my way to Kitchener-Waterloo and Grampa’s funeral… in my frozen hand, the weight of my grandfather and the family procession, orderly disciplined, a strange German march echoes from his gramophone—seems like a dream.

In ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) (1986), some camera report sheets filmed on the kitchen table in the Dovercourt Road apartment were made to look as if they were shot in Holland. The report sheets were carefully forged, made to look as if my shooting procedure is systematic, made to look like I’m in complete control, like Grandpa.

Toronto is a place to find work, to make and look at movies, to talk with people about movies. But I’m still not persuaded to shoot film in Toronto. I keep wanting to dig down into a past which is impossible to retrieve. Place is important to me but my work has little to do with concrete places like Toronto, Kitchener or even Lake McCullough. Place is where I am, what I think and feel, and for the time being I continue to find my place in Toronto.

(Originally published in A Play of History Catalogue (Toronto: Power Plant, February 1987)