by Brenda Longfellow

Phil tells an apocryphal story in my class at York University. It is a story about how, at the tender age of fourteen, as the designated documentarist of family life, he was asked to photograph his dead grandfather in his coffin. It was an indelible experience for the young man, so traumatic, in fact, that he put the film in a freezer and could only develop it years later.

It was his first dead body and his first photo assignment and whether or not this event represented a primal scene in the gestation of Hoffman the filmmaker, what is apparent in the body of films he has produced over the last twenty years is a profound meditation on the relation between death and the image, on the distinction between the sensual phenomenal world and the moment of time frozen in the flatness of a mortuary image.

In Camera Lucida/ Reflections on Photography, a book which serves so resonantly in reading Hoffman’s work, Roland Barthes argues that photograph has a historical relation with the “crisis of death” which he sees evolving in the second half of the nineteenth century.[1] Instead of trying to locate Photography in its social and economic context, he argues:

we should also inquire as to the anthropological place of Death and of the new image. For Death must be somewhere in a society; if it is no longer (or less intensely) in religion, it must be elsewhere; perhaps in this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life. Contemporary with the withdrawal of rites, Photography may correspond to the intrusion, in our modern society, of an asymbolic Death, outside of religion, outside of ritual, a kind of abrupt dive into literal Death. Life / Death: the paradigm is reduced to a simple click, the one separating the initial pose from the final point. [2](92)

Even with the incredible proliferation of image culture, the representation of death, that is, actual death, as opposed to the plethora of fictional deaths which fill popular culture, remains, as Amos Vogel puts it, “the one last taboo in cinema.”[3] If natural death in previous centuries, was integrated into the life of the community and culturally naturalized through ritual and religion, the increasing medicalization and technologization of death in the West, removed the experience from everyday life and invested it within impersonal legal and medical institutions. In these new contexts, death remains antiseptically invisible and shrouded in a veil of prudery.[4] Outside of the consistently diminishing power of official religion, the personal, emotional and philosophical content of death has barely begun to be addressed.

Vivian Sobchack has argued that the taboo of representing death in our culture is powerfully connected to “the mysterious and often frightening semiosis of the body.”[5]Death, in this instance, represents one of those primal threshold states, marking as it does as the distinction between being and non being, the transformation of human matter from one state into another. The act of photographing a corpse is experienced as trauma precisely because the corpse utterly confounds these cultural codes. Sobchack provides an elegant quote from “The Sacral Power of Death in Contemporary Experience,” which gets to the heart of this matter :

The flesh is more than instrumental to control and more than sensitive, it is also revelatory. A man reveals himself to his neighbour in and through the living flesh. He is one with his countenance, gestures, and the physical details of his speech. As some have put it, he not only has a body, he is his body. Part of the terror of death, then is that it threatens him with a loss of his revelatory power. The dreadfulness of the corpse lies in its claim to be the body of the person, while it is wholly unrevealing of the person. What was once so expressive of the human soul has suddenly become a mask.[6]

A corpse conveys the shocking transformation of the subject into a brute objecthood, devoid of consciousness, devoid of intentionality. For the young Phil, what I believe was traumatic about photographing his grandfather’s corpse was not only the cruelty of the silent and still body of a loved one but the insight it yielded, that photography, as a technology of reproduction, is inherently complicit in the transformation of subject into object. Every photograph, Barthes writes, is a reminder of Death because every photograph opens up that irreparable gap (which the photograph of the corpse is, perhaps, the limit case), between the intentionality and sensuality of the lived body and the flatness of the photographed body. Every photograph confronts us with the real absence of the loved one and with the irreversibility of time’s relentless forward movement. Every photograph is thus tinged with melancholy because of the loss which is ontologically inscribed in its very technology.

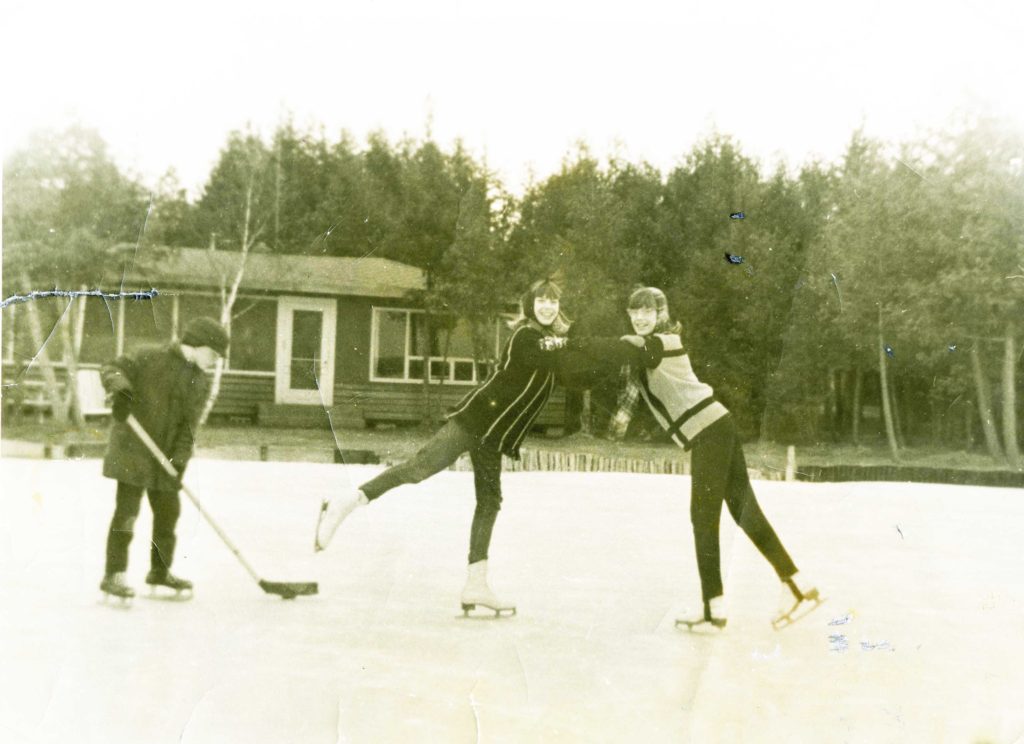

On the Pond (1978), Hoffman’s first film is paradigmatic of the importance of this insight in his work. This is certainly the film where the role of the photograph as an organizer of memory and as an index of an irretrievable past, the that has been that Barthes speaks of is the most prominent. The central structuring element in the film is a series of black and white family photographs of Phil, his parents and three sisters which are all thematically related to winter recreation, mainly ice skating and playing hockey at a pond in front of the family cottage. The sound is entirely non synchronous. Mapped onto that divide between sound and image, moreover, is the irreparable gap between the past of the images and the present of the auditory track which is filled with the family’s shrieks of recognition, delight and unabashed nostalgia. At one point, Franny, Phil’s sister laments “I want to go back” and it is precisely that desire and its ontological impossibility that structures the emotional content of the film. The voice of the filmmaker, however, is rarely heard in the family chorus yet he implicates himself in this nostalgia through a visual recreation featuring a young boy playing hockey on a pond. In this repeated image of the boy, it is as if Hoffman takes up that desire articulated by his sister, dissolving the veil between past and present through an act of imagination and filmmaking that restores a memory to the present. But it is a false and impossible note, a fantasy of a return to boyhood that can only be realized through the intercession of a fictional signifer as removed from the contemporary real as the family archive of family photos are.

As other writers in this collection are providing detailed readings of Phil’s middle works, I want only to linger on the opening images of Passing Through/Torn Formations as an additional indication of the thematic which I see running through all his work. Passing Through/Torn Formations opens in silence as a handheld camera continually pans over the face of Babji, Phil’s maternal grandmother, who lies dying in an institutional setting, a hospice or hospital whose cool institutional veneer has been somewhat humanized by the family photos, mementoes and cards pinned to the wall by her bed. Phil’s mother is feeding Babji, whose face, without her false teeth, is ravaged and skeletal. The camera lingers over the protruding veins in Babji’s thin arms, her stiffened hands, her gaunt cheeks, her eyes black with pain. Her “creatureliness,” as Sobchack puts it, foregrounded by the palpable fragility and vulnerability of her all too human body. Here again, Hoffman finds himself in a room recording a death. The trauma, however, is acted out by the persistence of movement, by the repetitions of that pan which refuses to rest in a final composition, which continually moves toward the curtain on the window as if to escape the claustrophobia of a room of the dying and of death. The eerie silence of the sequence confounds the sequence’s location in a real time and sends it, reeling, into the future-an image “catastrophe” in which the knowledge of certain death is already vested in the present/past of the image.

In Camera Lucida, while Barthes claimed that the cinematic image (as opposed to the still photographic image) avoided this sense of catastrophe through the continual unfolding of one offscreen space into another, it is clear that he is referring to the shot/reverse shot grammar of classical cinema and not to any particular ontology of the moving image. Indeed, in an essay which might in some respects be seen as the Ur text of Barthes’ insights in Camera Lucida, André Bazin, in his famous essay, The Ontology of the Photographic Image (first published in 1945)[7], already argued for the inextricable connection between photography and cinema precisely through their mutual capacity to “embalm time” against the certainty of death. In that instance, the difference between cinema as a time based medium and the photograph is erased in the more profound consideration given to how both are produced (through the photo-chemical action of light on film) as traces of the real.

A crucial distinction needs to be made, however, between fictional and documentary signifiers in film and photography. Vivian Sobchack argues that this difference inheres, not so much in the property of an image, as in the phenomenal experience of a spectator. As spectators, we have an entirely different relationship to the representation of bodies we understand share the same world as we do. Unlike the fictional signifier of death or of bodily destruction which figures solely for its entertainment value, the indexical qualities of the body represented in documentary (and in experimental documentary) call forth “an ethical space” that is, the visible representation or sign of the viewer’s subjective, lived, and moral relationship with the viewed. [8]

That is why, for me, the image of Phil’s mother feeding Babji is so moving. It calls forth a flood of memories of feeding my own parents on their deathbeds. And while using all of the experimental cinematic codes that defy realism: repetition, overprocessed stock, silence etc., the sequence, nonetheless, conveys the past/presence of an actual lived body, one that solicits our profound empathy.

If the indexical quality of that body in the opening sequence anchors the film in a relationship to the real and to the acknowledgement of impending death, the remainder of the film proposes memory, storytelling and retracing the past as defenses against that inevitability. As rich and layered as a dream, the film voyages between Poland, the land of Babji and his mother’s birth and Kitchener, home of his Uncle…… If family history was registered as overly bucolic in On the Pond, Passing Through/Torn Formations delves into the other side, the dark histories …..abandonment and depression, the stories that the public archive of family photos does not tell. Supported by the richly textured pans of stones, crumbling fences and pavements, Passing Through is metaphorically associated with an archaeological dig through history but the result, in this instance, is not a seamless whole artifact but a jagged and disjointed assemblage of multiple shards of stories. Like the dream, these stories are layered, like the images themselves, one on top of the other to form a palimpsest of memory, memory as palimpsest. No coherent gestalt or linear family history can be forged from these fragments. What is left to the filmmaker is to bear ethical witness to that impossibility, to continually record and photograph life, hunting and collecting images of everyday life against loss and against forgetting.

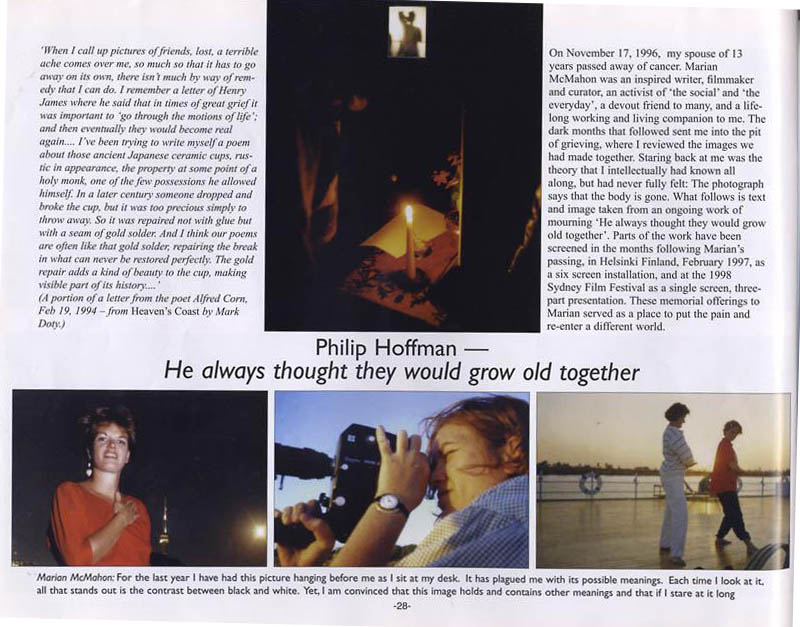

Phil Hoffman’s new film, (untitled as of this writing) also opens with a long silent sequence featuring his late partner, Marian McMahon frolicking in the snow at their farmhouse in eastern Ontario. Marion, as she was in life, is full of spirit and mischief playing to the camera with that goofy quality that Canadians take on in the dead of winter. There is something so fundamentally idiosyncratic about her image: the funny red ear muffs, the vintage stripped scarf, the thickness of those wooly socks pulled over her jeans, those stubborn details that affirm the irreducible uniqueness of the individual, that persist despite the inevitability of human mortality. They are what Barthes defines as the punctum the accidental, the coincidental, the telling detail which “pricks the spectator.” For Barthes, this is the order of love:

the Photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially. In the Photograph, the event is never transcended for the sake of something else: the Photograph always leads the corpus I need back to the body I see; it is the absolute Particular, the sovereign Contingency, matte and somehow stupid, the This …in short, what Lacan calls the Tuché, the Occasion, the Encounter, the Real, in its indefatigable expression. The off centred detail…the materiality of the particular that. ..won’t and cannot be named.[9]

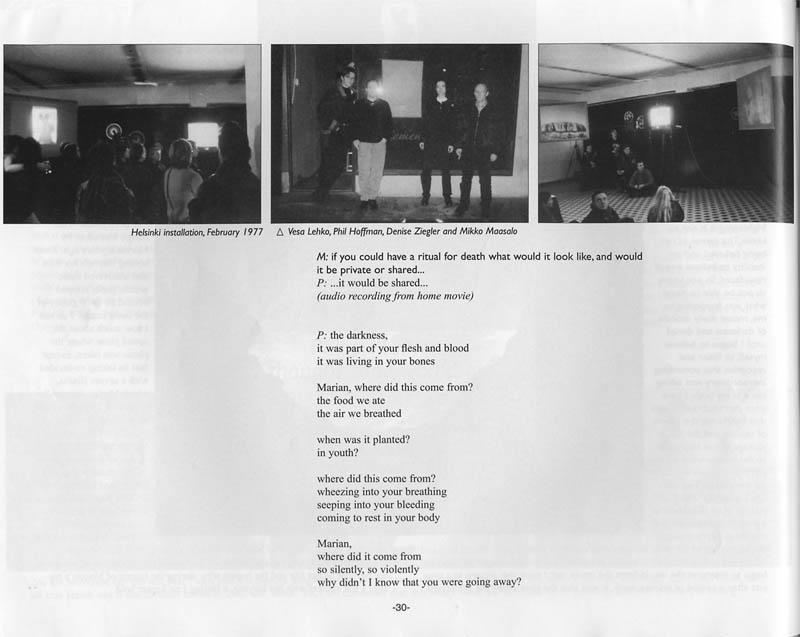

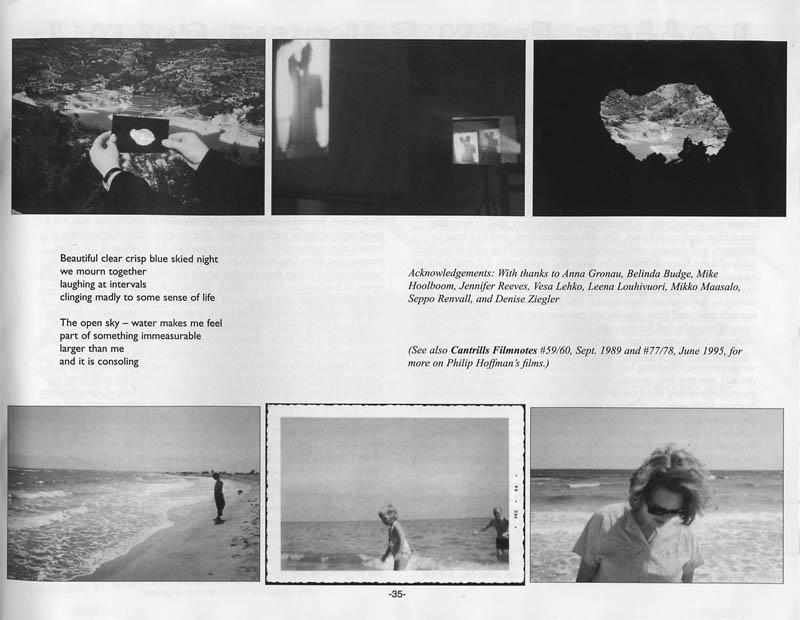

If so much of Phil’s work involves a meditation on death and the image, that meditation has its most personal articulation in his new work. It is a film explicitly about death, about the particular death of Marian, lover and life partner and about the emotional fallout experienced by the filmmaker as a result of that loss. It is a film about mourning, about how to mourn, about styles of mourning. In the latter part of the film a question is posed by Marian in voice over: “What ritual would you invent for death, would it be public or private ?” Hoffman responds “Public.” This film is his public elegy and while intimately and achingly sad, it is also a film, to borrow a strange word from Peter Harcourt, about redemption and the redemptive possibilities of that mourning.

In “Mourning and Melancholia” Freud described mourning as process “so intense” that it resembles a temporary psychosis. Overcome with grief, unable to reconcile oneself with the painful actuality of loss, the subject clings to the lost love object “through the medium of a hallucinatory wishful psychosis… Each single one of the memories and expectations in which the libido is bound to the object is brought up and hypercathected” (253) but each is met by “the verdict of reality” that the object no longer exists.[10] In normal “successful” mourning the narcissistic satisfactions of the ego win out and, though a painful and slow process, libido is eventually withdrawn from the lost object and transferred onto a new one. Proper mourning, then, according to Freud, is like a narrative, it has a beginning, middle and end (and in that order) and its goal is to restore order, to reintegrate the subject to back into the world and into the reality principle.

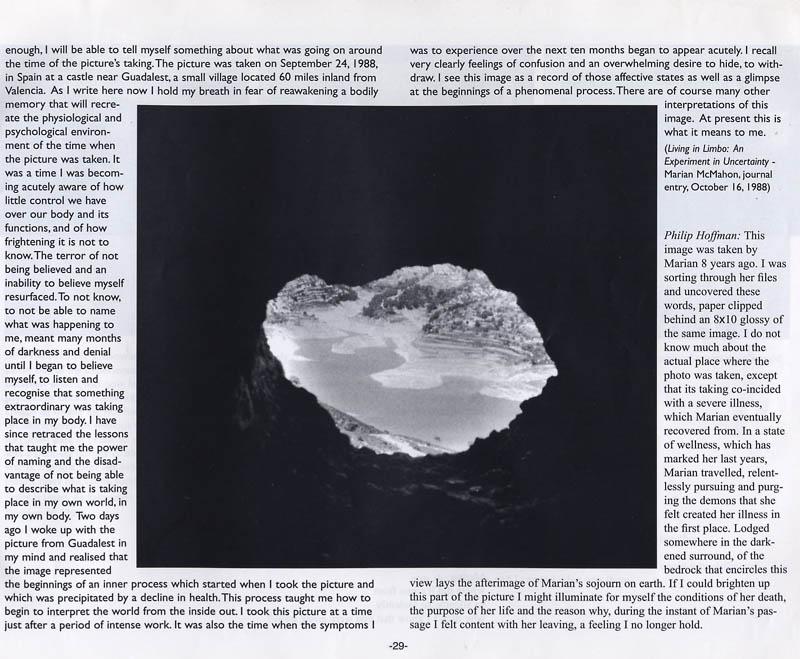

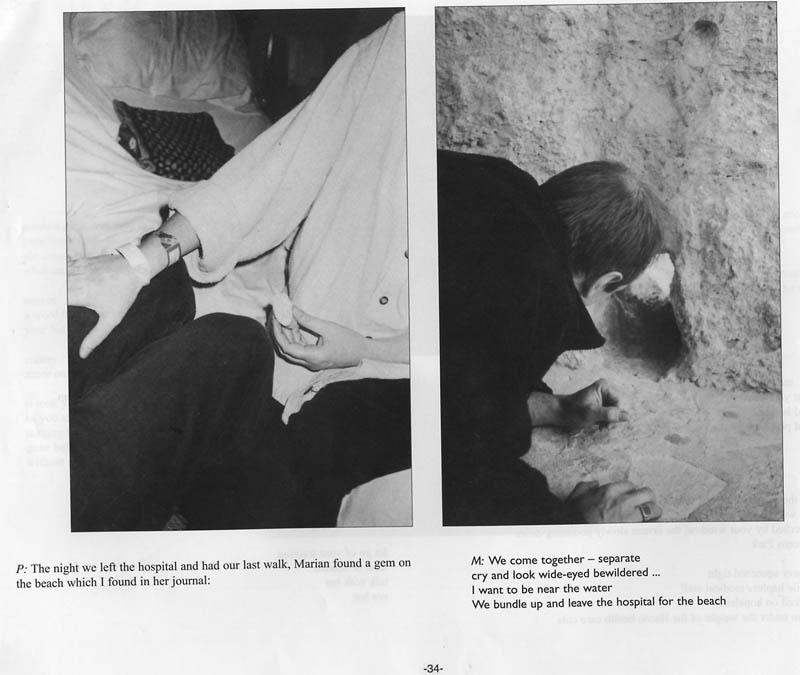

But what if the proper is resisted and the subject refuses to disassociate affective connection with the lost loved one ? In one of the most lyrical sequences in the film, a text by Hoffman dissolves in over a photo of a seaside landscape taken by Marian in Spain: “If I could brighten up this part of the picture, I might illuminate the conditions of her death, the purpose of her life and the reason why, during the instant of Marian’s passage, I felt content with her leaving, a feeling I no longer hold.” His body still longs for her, he confesses, his mind still imagines her, his soul still aches. The loss remains fully present.

In Mémoires: For Paul de Man,[11] Derrida puzzles as well with this issue of “proper” mourning. Within the classical Freudian conception of the term, successful mourning is equivalent to the assimilation of the object into the self and to an eventual forgetting of the loved one. But does this assimilation, this “eating of the other,” Derrida asks, not eradicate the irreducible altereity of the other ? This is a profoundly ethical question for Derrida : how to honour the otherness of the other while at the same time acknowledging that within the act of mourning, the other is always an object “image, idol, or ideal” that one constructs oneself.

For me that is the resonance associated with the second long sequence in the film which uses video footage of Marian working in her day job as a VON (Victoria Order of Nurses). In the footage, she is the most punky and weird of VON’s with her butch haircut, smoking cigarettes, speculating philosophically on the issue of touching a stranger’s body. At one point, however, she confronts Phil (hiding behind his 3/4 inch video camera in the back seat) accusing him of not understanding how difficult it is to be filmed and how much the camera mediates and makes strange their relation. It is an important moment precisely because it honours the otherness of the other. The only synch sequence in the film, it anchors Marian in her lifeworld, not simply as an image, idol or memory but as a sensate and intentional subject in her own right and one, furthermore, who explicitly defies the naturalness of a camera recording her image.

What one misses in mourning, speculates Derrida, is the response of the other, the voice of the other, the return serve in the dialogue that has structured the couple. Making the film in her absence, with the bits of images and audio fragments left behind, allows Hoffman, the filmmaker, to reconstitute that dialogue. In one sequence, for example, images of a trip to Egypt, to the view from their hotel window fade in as the voice of Marian, waking up from a siesta, recounts a dream: “We went back to Canada. Everything had changed but everything was familiar. What I most remember was walking in the snow with you.” What the film does is implicate itself in this dream, remembering and imagining for Marian, allowing her vision to call forth images. The recounting of this dream lends a retroactive meaning to the opening sequence of Marian in the snow and is linked, associatively, with later sequences of shadows of two people falling on a snowy lane.

The recovery of the loved one’s voice is also undertaken in the sequence featuring the photograph Marian had taken in Spain, although the voice can only be present in its absence, as a printed text superimposed over the image. In many ways, this sequence in which texts by Marian and Hoffman both endeavour to tease out a meaning ostensibly hidden in the photograph, act as a key fulcrum in the entire film. For Marian, the image, taken at a castle near Guadalest, 60 miles from Valencia “reawakens a bodily memory,” and reminds her of a point in the past when she was becoming acutely aware of extraordinary changes happening in her body which, retroactively, seemed to signal the return of a disease that she felt she had been cured of. Going through her affects after her death, Phil discovers this text paper by Marian clipped to the back of the image. His text introduces and closes the sequence, reflecting on Marian reflecting on this image, seeing in the photograph a mysterious and cryptic relic that might reveal “the conditions of her death” and “the purpose of her life.” The photograph itself is banal, a seaside landscape, a tourist image, conventional and undistinguished, as “boring” as looking through another person’s photo albums. Yet, the photo functions as a blank slate, a void whose meaning is produced associatively (ie. not referentially) entirely through personal memory and projection. In that, the sequence acts as a kind of condensation of the series of questions that I’ve argued are central to Phil’s work. How does meaning adhere to an image ? How do images organize and create memory? How does death and the absence of the loved one imbue the image with its beauty and its mystery?

In Mourning and Melancholy Freud experiences some difficulty in definitely distinguishing between the two psychic states. In one instance he posits melancholy as a an unresolved form of mourning where instead of assimilating the other into the ego, the ego identifies with the lost object, as he puts it: “the shadow of the object fell upon the ego [and] the ego is altered by identification.”[12] For Derrida, this is precisely the formulation of love where the other is taken into oneself, not in the service of obliterating difference but of preserving otherness, an otherness whose effect is to alter my being. While I do believe this is the style of mourning and love that Hoffman proposes in his film, let me suggest that Freud’s alternative conceptualization of melancholy may be of some use here. In the second formulation, melancholy is without a specified object. The subject experiences overwhelming sadness but without being able to attribute it to any particular cause: it is a generalized sense of loss. This generalized sense of loss has an uncanny resonance with a thematic that I have argued is central both to Barthes’ formulations in Camera Lucida and to the cinematic oeuvre of Philip Hoffman. In those instances, melancholia has to do, not with the particularity of this death, but perhaps with Death itself, its inevitability and the appraisal of the fleetingness and ephemerality of life. It is this emotional quality which makes photography and experimental film among the more melancholic of arts.

References

[1]. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983).

[2]. Barthes, 92.

[3]. Amos Vogel as quoted in Vivian Sobchack, Inscribing Ethical Space: Ten Propositions on Death, Representation, and Documentary, Quarterly Review of Film Studies, vol.9, no.4 (1984), 283.

[4]. Perhaps only the Aids crisis and the politics of representation it has generated has forced images of death and the dying body again into public consciousness.

[5]. Sobchack, 286.

[6]. William F. May, as quoted in Vivian Sobchack, 288. (Original citation: The Sacral Power of Death in Contemporary Experience, in Death in American Experience, ed. Arien Mack (New York: Schocken Books, 1973), p.116.)

[7]. Andre Bazin, The Ontology of the Photographic Image, What Is Cinema?, trans. Hugh Gray, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967).

[8]. Sobchack, 292.

[9]. Barthes, 40.

[10]. Sigmund Freud, Mourning and Melancohia, On Metapsychology, vol 11, trans.James Strachey (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1984), 253.

[11]. Jacques Derrida, Memoires: For Paul de Man, trans. Cecile Lindsay, Jonathon Culler Eduardo Cadava, and Peggy Kamuf. Ed. Avital Ronell and Eduardo Cadava.(New York: Columbia UP, 1989). Much of my argument re Derrida is drawn from Penelope Deutscher, Mourning the Other, Cultural Cannibalism, and the Politics of Friendship (Jacques Derrida and Luce Irigaray), differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol. 10.3 (1998), 159-184.

[12]. Freud, 258.