Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) here

Mike Hoolboom on `Somewhere Between…’ Here

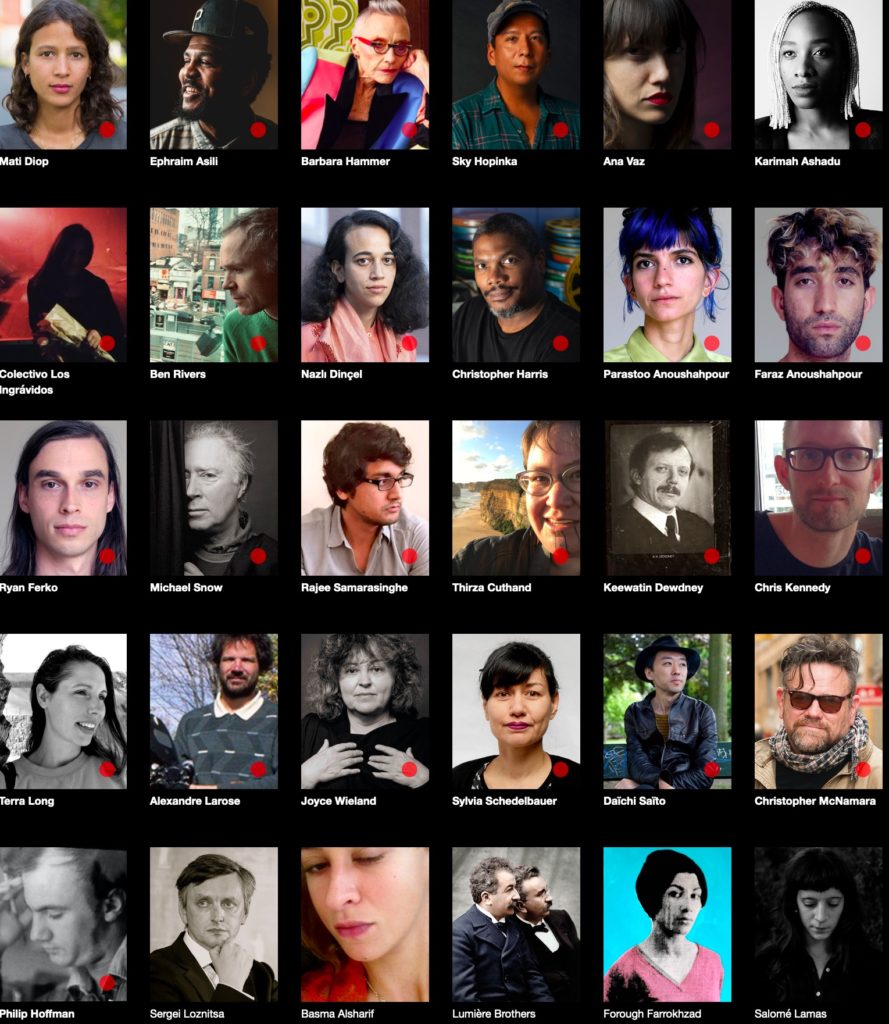

1000SunsCinema Streaming Program at Media City Here

July 2001

Dear Phillip Hoffman

RE: Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan & Encarnacion

The same movie but “Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion”(Philip Hoffman’s ) is short movie clip and ?O, Zoo! is longer movie is fiction thing. Can you send me the copy of special movie “Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion” and ?O, Zoo!”? are the free movies home video cassettes? My parent from Jalostotitlan, Mexico. I am born in Mexico City. I am surprise you were filmed in small Mexican town called “Jalostotitlan” in 1984. I want thank You did filmed in Jalostotitlan because many Tourist people come visit in Jalostotitlan, Mexico. Can you send me the free Catalog? Also Can you make copy of VHS for :”Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion” and ?O, Zoo!? Because I not find the Home Video (I Need Rent a Movie) from Blockbuster Video (Popular bigger Video Store in United State of America and Mexico). I am just ask you about should add closed captioned on “Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion” and ?O, Zoo!” on new release home video? Because I am Hard Hearing should watch the two movie called “but “Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion” and “?O, Zoo!”?

Thank You,

Juan Antonio De La Torre

From: Philip Hoffman

Sent: Tuesday, July 10, 2001 7:16 AM

To: Johnny De La Torre

Hi, I can send you the movie “Somewhere Between”….there is only music so you can turn it up loud… ?O,Zoo! would be much harder as there are alot of words in it…”Somewhere Between”is about an experience I had in 1983, on a bus (between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion) when a boy was killed on the road…I decided not to film him out of respect for his soul and the people…I was troubled by the event so I made a film from other images of Mexico, Colorado and Toronto…hope you like the film…it is a poem and so it would never be in a place like Blockbuster Video store….

bye for now,

Philip

Hello Phillip Hoffman

I was sent you my address already.. I Love Mexican town called “Jalostotitlan” is very popular because Big Celebration for Mother of God “Virgin” for Birthday on August, On February for Celebration Spanish (Now “Mexico”) Explored was settlement (1530) in Jalostotitlan in Mexico… I want thank you did Filmed. You always become Famous who films in Jalostotitlan for “First Time” You are first Canadian who filmed in Jalostotitlan in the world. No On American who came in film in Jalostotitlan.

Thank You,

Johnny De La Torre

by Donnalee Downe

23 November 1984

DD: Can you tell me a bit about how you went about shooting and editing Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion?

PH: I had been reading some Haiku poetry at the time. Haiku is a Japanese form of poetry which is very simple, yet complex in its simplicity. In fact, when I went down to Colorado that was a poetry convention of sorts. So I decided what I wanted to do in Mexico was shoot in a similar fashion, borrowing from the form of Haiku poetry. I tried to think of the Bolex camera’s twenty-eight second wind as a structure rather than a limitation. Most of the shots in the film are twenty-eight second takes: the “breath” of the Bolex camera.

I tried to make each shot sparse in its content: the coke sign, the donkey, the open road, the mother and child running, (c) simple, uncomplicated shots. In shooting The Road Ended at the Beach, I had a lot of expectations… about “the big trip”. I felt I had to make the film, it was my first since school. There was a lot of pressure and tension and not much fun. So it was important with Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion to shoot when I felt like shooting so it would be more like writing poetry.

DD: But it wasn’t until you returned that you decided it would revolve around an image you didn’t have.

PH: Right. So in a way it was a lot of little poems. On the trip I kept a journal and I tried to write little phrases based on the haiku form. Not that it was at all like traditional haiku. I tried to develop a style, to let a form develop out of an idea. When I came back from the trip I didn’t know what the film would be about. I hadn’t shot that much film—about seventeen minutes—and the film is only six minutes long, so it was pretty economical. When I came back, the experience on the bus was still on my mind. I didn’t have the footage and didn’t regret not having it, it was something I just didn’t want to do at the time. I remember putting the camera down and thinking no, I don’t want to do this.

DD: The sparse images you described facilitate open interpretation. The emptiness opens to the missing image.

PH: They’re open but there are still some things that were on my mind while shooting. I kept going back to the churches.

DD: Are the religious images linked to the boy’s death?

PH: No, they’re a reflection on my own experience as a Catholic. Religion is most visual in Mexico. I was interested in icons and in the beat people—beatific in the Kerouac sense—sympathy to humanity. I see more spirit in the people than in the icons, let’s put it that way.

DD: How do icons function in the film? We talked earlier about film language. The meaning of the images is largely defined through the film itself through their relation to the death, and yet the icons have such strong connotations.

PH: Yes you can interpret an icon in many ways. For me it was a way of working through Catholicism. You’ll see more of it in my next film.

DD: Did you decide to tone the black and white footage to facilitate a less dramatic contrast with the colour footage?

PH: From a formal standpoint it helps blend the high-contrast shots with the colour. I also wanted it to look old—but not the way we are used to seeing representations of the past in film. Hollywood uses sepia. My first text states “looking through the lens/ at passing events,/ I recall what once was/ and consider what might be.” The first shot is of a black band. We hear the music of a saxophone and see a trumpet. There’s a sort of visual/aural pun there. We’re used to sync sound, but in the last line of the preceding text it’s clear that, well, with film we can do whatever we want.

DD: In the text you changed tenses. For example in the third text: “The white sheet is pulled over the dead boy’s body/ the children wept.” It’s almost like looking at someone’s memory. The temporal connections are unclear but we’re content with ambiguity.

PH: I believe in an open form where you’re not told what to think. I suppose it is a metaphor for memory. I honestly didn’t think about the different tenses in the text, I went with what sounded good to my ear. It jumps around and that’s in keeping with putting myself in the past while making, finding myself on the bus again, while I’m really at home in my Bathurst Street basement.

DD: The shot with the Coke sign and the donkey cart has temporal ambiguity too. The sign is obviously modern and the cart so primitive.

PH: Again, there are many ways this can be taken and the ambiguity is important. For example, the last text: “big trucks spit black smoke/ clouds hung/ the boy’s spirit left through its blue.” What is that blue? Is it blue smoke from the trucks? The blue of the brick wall?

DD: It brought me back to the wall.

PH: It did? That’s one of the things I liked about the line. It is ambiguous and I don’t profess to have an answer. To end on a line like this ” the boy’s spirit left through the blue” it’s almost like a traditional religious experience. I suppose this brings us back to my Catholic history and the icons in the film. The line is directly from the journal and was written on the bus. I suppose it was the blue sky that I saw at the time.

DD: I’m comfortable with ambiguity. I guess it’s partly because the second text tells me that there’s no footage of the central image. I don’t have expectations. I don’t wonder how the boy died.

PH: It was the second death I’d seen on the trip. The first was a terrible car accident in Colorado. I didn’t film that either. The windshield was the movie screen and the camera was right there, but no way.

DD: Do you remember deciding not to film the Mexican boy?

PH: I remember my hand on the camera and it would have just been a matter of leaning out. I guess all the media footage we see every day flashed through my head.

DD: I think the absence of the footage is more striking. We’re saturated with media-like images.

PH: Well, the media images are striking, but I think in this case actual footage wouldn’t leave any room for analysis of death and our feeling towards it. Media images are too overpowering. That’s why I put the camera down. I think it’s more successful as a meditation in its absence. There is another text which I think is awkward, yet perhaps one of the most important: “I should have a bible,/ you suppose I lent it to someone/or someone stole it.” Most people ask, “Is that poetry?” It brings us back to the first person that’s having this experience. For me, it symbolizes a loss of religious faith in the Word, in the icon, in what we’re taught in religious classes. Today the Bible seems irrelevant. People take whatever meaning they want and use it for their own cause… and yet the Bible (like the film) is an open form. Its ambiguity facilitates many interpretations.

DD: I guess it’s a question of how didactic one is about a particular interpretation.

PH: Perhaps that’s how it should be read. Let people read it and take out of it what relates to their experience… rather than Jim Baker and the P.T.L. Club saying what it means.

DD: For me, the music really helps define my proximity to the central image. When the tempo is upbeat, in the shots of the two bands for example, the boy is almost forgotten. When the music slows I feel closer to the tragic event. Can you explain how you and the musician decided upon the music?

PH: I showed Mike the film and we worked on it together. I left the film with him and he worked with it and soon certain riffs started to develop, and then it was just a matter of getting it right. We did six takes and I edited the first version which I wasn’t really happy with. Because it was edited it didn’t seem continuous, it didn’t seem to flow, so we tried again. This recording went directly to 16mm magnetic tape. There were things that he did that, if he was three frames off, it would change the mood completely. We did seven new takes and finally we felt we had it. We were both really tired but decided to try one more and we got it. Only one section was edited, I took that whole section from the sixth take. I think it’s hard to write the music down, it’s certainly possible but perhaps it’s not as direct. I like to work in a way so that everything comes out of experience.

DD: The diarist of The Road Ended at the Beach expresses frustration and disappointment at the failure of events to live up to expectation. One has a strong sense that the camera comes between you and your fellow travelers, thatit distorts what you want to record.

PH: At one point in this film I state: “The best time for me is when I’m on my own with the camera.” Later there’s another reference to how the camera gets in the way. At this point the spectator realizes that the camera is part of the event. In the first part of the film we are painting the van, it’s very mysterious. The guys are preparing for the trip west. It’s very linear at first, setting up the form. I suppose one of the first references to the camera is in a shot in the cabin. Rub Chan asks me if I want some whisky and starts to get up. Richard says, “No, No, No, don’t get up.” And I get out from behind the camera. It’s the first filmic reference to the camera. There are a lot of problems with directly autobiographical films. It seems that when a film is too direct, too personal, you meet a lot of obstacles. I tried to use my personal experiences as a vehicle for something more universal. In Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion the universal experience is death. It’s an analysis, not just of personal experience, but of how this experience is incorporated in a much larger context.

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

looking through the lens at passing events,

I recall what once was and consider what might me

ENTER UPBEAT MUSIC – SOLO SAX

(black and white)

A man plays a trumpet in an outdoor street mall in front of some shops in Boulder, Colorado. He is wearing dress pants, a white golf shirt and a top hat. To his left are two men sitting, one playing on a makeshift drum set and one playing a banjo. In the background a few pedestrians stroll by paying no attention to the black street band.

MUSIC SLOWS ITS PACE

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

Somewhere Between

Jalostotilan and Encarnation

There is a static shot (color) of a street corner in a small Mexican town. The sky is blue with a few clouds. The street is vacant except for a man sitting in his buggy drawn by a donkey. The street scene is dwarfed by a huge Coca Cola sign. A white taxicab with green stripes drives down the horizontal street followed by a yellow pick-up truck (frame left to right). A child, followed by mother, jog across the vacant street, to the opposite side of the road. They begin to walk down the sidewalk of the street.

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

on the road dead, lies a Mexican youth

I put down the camera

the cop car passed right by

MUSIC SOFTENS

A shot, framed between two pillars, shows the partial view of an interior of a church. Moveable chairs sit in rows facing frame right. There is an isle between them, making two sections. Two children enter frame left and sit on the two chairs on the outer sections at the edge of the isle. They talk amongst themselves. A third, smaller child enters frame left and walks down the isle to the row ahead of the two who are sitting. The child looks back at the two and tries to climb up onto the seat. Unable to do this, she looks back at the pair and attempts the climb again.

A hand-held dolly shot (frame right to left) exposes the degrading walls of a Mexican street. The camera pans right to include the alley being traveled upon. On the opposite side of the road is a line of parked cars in front of some two-story houses with white windowpanes. The camera tilts up the paint chipped wall towards the clear sky. Above the wall towers the steeple of a church.

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

reaching out, the white sheet

is pulled over the dead boy’s body

the children wept

In the distance a group of people are gathered just outside the pillared entrance to a Roman Catholic church. They all face away from the camera, kneeling on the cobblestone walkway outside. A few people enter frame right and join the Mexican worshippers.

A hand-held dolly shot (frame left to right) faces the bare walls of the exterior of some houses. As the camera turns a corner, the alley can be seen, as well as two lovers embracing in the corner. At the end of the narrow alley is a ‘T’ junction created by another building.

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

i should have a bible.

you suppose I lent it to someone

or someone stole it

SOLO SAX MUSIC PICKS UP TEMPO

PARTIAL DISSOLVE ENCOMPASSES 2-3 LAYERED IMAGES

A painter sits on a chair in front of a painting of Jesus. He is painting a copy.

A close up shot of painter. He continues to paint a copy of the face of Jesus.

Cars pass by on a roadway, a blue brick wall covers the frame.

A close up shot of a brush paints Jesus. The camera pans down the brush to the painter’s hand.

In a profile shot, the painter paints the brow of Jesus. The `original’ painting faces the camera.

An extreme close up shot of the religious painting.

A static shot of a blue brick wall.

THE SECONDARY IMAGE 2 IS CUT

A religious procession, ` The Feast of Fatima,’ makes its way up Bathurst Street in Toronto. A girl in a white dress and veil walks past and looks towards the camera (right to left).

A pair of kids dressed in angel-like costumes walk in front of the camera and out of frame (right to left).

THE THIRD IMAGE 2 IS CUT

Cars pass through and intersection where the kids crossed as two more people walks past the camera in religious costumes and look at the camera.

A low angle shot films the top of a house and an overcast sky masked by power lines. The statue of Jesus rolls through the frame (right to left).

(Secondary Image 3) The camera tilts down to a group of Portuguese worshippers walking dressed in religious attire, carrying the statue. Some look at the camera.

A close up shot of ladies faces cross the frame (right to left). They looks into the camera. More people cross the frame.

*****Shot Altered from Dominant Primary Image 5 to Secondary Image 4

An extreme close up of the bottom of a woman’s white dress crosses the frame (left to right). The camera pans to the right and exposes a line of people walking down the street (left to right).

CUT SECONDARY IMAGE 4

*****Shot Altered from Primary Image 6 to Secondary Image 5

Dominant Primary Image 7

A low angle shot of a Mary statue clasping her hands passes through the frame (right to left).

SOLO SAX MUSIC LIGHTENS AND THEN BUILDS THROUGH NEXT SHOT

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

The beggars stopped me

A voice through the window.

I gave the young girl a peso

A hand-held shot travels from left to right down a sidewalk. A young child wearing a white dress stands in front of a paint chipped stone wall. She has one hand to her mouth and the other holding out a silver shiny tray. The camera continues to travel towards a group of Mexican street musicians. A man wearing a dress shirt, dress pants and black cowboy hat plays a trumpet. To his left are two young kids. The one in the foreground is standing still looking away from the camera, the other stands against the wall in behind the first playing a drum that is harnessed around his neck. To their left, a man is playing a large drum.

SOLO SAX MUSIC LIGHTENS

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

the little girl

with big eyes

waits by her dead brother.

(Black and White)

In an outdoor street mall in Boulder, Colorado is a large snail sculpture with a massive shell which faces the camera. On top of the `snail’ sits a young girl who is pushing down on the shell, in rhythm to the music

(Black and White)

A rippling pond sits before a forested area that leads to a street with bypassing cars

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

big trucks spit black smoke

clouds hang

the boys spirit left through its blue

SOLO SAX MUSIC ENDS

END TITLES

(an excerpt from a larger article publication forthcoming)

by Janine Marchessault

I was still a young boy when I saw my first film. The impression it made upon me must have been intoxicating, for I there and then determined to commit my experience to writing…. I immediately put on a shred of paper, Film as the Discoverer of the Marvels of Everyday Life, the title read. And I remember, as if it were today the marvels themselves. What thrilled me so deeply was an ordinary suburban street, filled with lights and shadows, which transfigured it. Several trees stood about, and there was in the foreground a puddle reflecting invisible house façades and a piece of the sky. Then a breeze moved the shadows, and the façades with sky below began to waver. The trembling upper world in the dirty puddle—this image has never left me.

— Siegfried Kracauer (Ii, 1960)

We can see the development of strategies based on coincidence, accidents, indeterminacy, endlessness, and contingency in documentary and experimental filmmaking of the post war period expressly in this light. As a means to work through some of Kracauer’s insights around cinema and the “whole world”, let me turn to a specific work—the short ‘travel’ film Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) by Canadian filmmaker Philip Hoffman. The film was shot under the influence of Jack Kerouac and inspired by the Beat Generation. Kerouac went on the road in the fifties to wander and to have experiences, to create a scene across cities, New York, San Francisco and Mexico. ‘On the road’ refers specifically to a mode of writing that is quite literally writing while en route. It is after The Town and the City and through On the Road that Kerouac developed his art of ‘spontaneous prose’, an improvisational method of writing in time connected to the flow of life like jazz. Famously he used a full roll of Teletype paper that matched the road and typed the novel almost continuously over three weeks. The roll enabled him to write without stopping, without interrupting the flow of words, essentially mirroring the experience of driving. Kerouac like Gertrude Stein before him, associates writing with a phenomenology of the mind, a writing that is “composed on the tongue rather than paper” (Ginsberg 74). Kerouac’s writing does not seek to transcend mediation so much as it does to document its actions so that writing becomes a record of the connection between inner and outer structures of perception, binding bodies to places through time. As much as it pushes the boundaries of presentness, writing like film, is always in the past. Although the fact of mediation between word and image is altogether different as Kracauer would stress.

Hoffman made Somewhere Between, after attending a conference devoted to the legacy of On the Road in Boulder, Colorado. Yet Hoffman’s film is not so much on the road (the highway) as it is on the street, featuring two cities (Boulder and Toronto) and towns somewhere between the cities of Guadalajara and León. The film cuts across various scenes in these places with lengthy (often twenty-eight seconds) unedited sequences of action and black leader as “measured pauses” (Kerouac’s silence or breath) between sequences. These juxtaposed moments play out a reflexive rhythm that foreground the randomness and stubborn indeterminacy of the images of everyday life, and of their placement in the film. We are presented with situations that are delimited without being explicated. The film opens with a text on the screen: “Looking through the lens/ at passing events/I recall what once was /and consider what might be.” Two early sequences in the film give image to these words. The first is an image of what is now a cliché of globalization. The static camera poised on a street corner in the centre of a small town in Mexico, frames in long shot, a mule and buggy parked beneath a large red Coca-Cola sign, a tangle of telephone wires above low rise dilapidated buildings. The only movement in the frame is the cars, driving in and out of it, and a woman and child crossing the street. Yet movement and layers of interaction are implicit in the juxtaposition of the mule and the global corporation, which co-exist in this place. This image is preceded by another static shot of a church down the street, doubly framed between two pillars of a Catholic arch. Looking in, the camera reveals someone deep in prayer. After a motionless few seconds, a child interrupts the stillness of the sequence, enters the frame and begins a game of crawling up and down on chairs. The child’s sudden appearance is precisely that kind of “unexpected incident” that Kracauer delights in—“the stirring” of nature and people that the Lumiére films first captured. The kind of “spontaneous writing” that we often find in experimental ethnographies favors a self-reflexive methodology[1]. In this instance, focusing on the physicality of the scene to include the temporal structure imposed by the camera (i.e., the spring wound Bolex’s 28 second take) and the filmmaker. The acts of “looking through the lens” as Hoffman’s text tells us, calls upon a time-based aesthetic where past and future co-exist beyond the edges of the frame. Yet it is not only the film strip/ flow of life analogy that foregrounds this temporality. It is also the reoccurring themes of religion and children, of tradition and horizons that Hoffman finds across the different places in the film. Given that the film concerns the story of a Mexican boy run over by a truck somewhere in Mexico, these themes resonate throughout. The boy’s death is an event that the filmmaker refuses to film (or include in the film) but instead conveys through a poetic text on the screen that is intercut throughout the film. Filled with black holes overwritten with the poem that remembers the boy’s death, the film’s architectonics are structured by the words that never conflate the commonalities between the situations. The poem embeds the boy’s death in all of the images of the film so that it is not inconsequential to the corporate sign, the superstructure in the opening images but rather stands in a contiguous relationship to it as to all the images in the film. The melancholic saxophone that draws the line from Mexico to Colorado to Toronto, seems to synchronize momentarily with the musicians and children holding out cups to collect money in these different places but then separates and floats over them from an off screen space that leaves the frame open to a multiplicity of found stories: children playing games on different streets in different cities, a crowd kneeling outside a church, the Feast of Fatima procession in a Portuguese neighborhood in Toronto, little girls dressed as angels and streets lined with telephone poles, the beautiful patina of pealing walls aged by the weather, graffiti palimpsests in different languages, a paint brush sketching a likeness of Jesus from a painting of Jesus, a child crawling up and down on a large sculpture of a sea shell in an outdoor street mall, a pond surrounded by trees at dusk. The camera stages situations from a distance and in long shot; sometimes the movements of bodies are slowed. But it is the materiality of the built environment that is framed to equalize the human and the non-human (trees, benches, windows, sidewalks, statues, cars, signs) which are counter influencing and interpenetrating processes. We see here the manifestations global cultures, national and urban idioms and technologies that the film stages as commonplace.

In the study of localities, filmmaker and anthropologist David MacDougal points out that it is not singularities but interconnectivities and flows between particular cultures that lead to the cinema’s capacity for deeply phenomenological and pedagogical gestures. Somewhere Between gives us the interval or the interface between places where identities and experiences take up their meanings in Hoffman’s memories of a shared world. Yet it is also the characteristic of the “found story” that it remains open, fragmented, that it burn through myths and clichés. It must resist the “self-contained whole” that would betray its force by casting a tight structure with a beginning, middle and end around its anonymous core. The found story Kracauer explains arises out of and dissolves into the material environment, often in “embryonic” forms that reveal patterns of collectivity (Theory 246). The found story comes from the aesthetic of the street and we should add, holds infinite possibilities for the psychic investment in the whole even as it takes it apart. In the end, Hoffman may well have broken with Kracauer’s prescriptive visual aesthetics by staging reality with word, image and black leader in a way that actively petitions the dreamer to envision what was and what might be. What holds the spectator’s interest in Hoffman’s film is the gap, the place of imagining: the black smoke from the truck, the children weeping, the sky and the boy’s spirit as it “left through its blue”.

[1] Take for example the films of Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Jean Rouch, Agnes Varda or Chris Marker who use the camera as an intrinsic aspect of performance. We could also include some of the more self-reflexive documentaries by the Unit B directors at the NFB of Canada. Cf. Catherine Russell Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video (1999).

Read whole article here

by Jeremy Rigsby

Travelogues are films made by tourists. They are defined by their creators’ decision to remain on unfamiliar terms with unfamiliar surroundings. These are not documentaries, which presume or strive for some unmediated relation to their subjects. Unless they can demonstrate that they are provisional and selective, documentaries are prone to be mistaken for the truth. Unless they can demonstrate that they are art, travelogues are largely the product of hobbyists who can afford vacations. Travelogues may affirm their artfulness by appealing to an aesthetic derived from the lyrical avant-garde, or, more frequently, by adopting the discursive strategies of fiction films. Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion takes the latter route, all the way to a Mexican crossroads of the Real and the Imaginary.

The fictive convention relied upon by Somewhere Between establishes an artificial contiguity between the film’s two discrete components: intertitles alternating with images (of Mexico, mostly). This convention is associative editing, a neat version of the so-called Kuleshov effect, whereby details noted in the intertitles are presumed to refer to the images they immediately follow or anticipate by the simple virtue of proximity. The dead youth is nowhere seen or implied in any of the footage. The titles state that Hoffman “put the camera down.” But the cop car that sped by his corpse must be the very one just seen passing the Coke billboard. Likewise the beggar girl who was conceded a peso is identified as the beggar girl who then appears. And the girl with the big eyes awaiting her dead brother? There she is, her imputed lingering iterated by symbolic association with a concrete snail. Much of the film’s remaining footage is neutral and irrelevant to the text, but marshaled to support a funereal aura through melancholy slow motion or sepulchral, greenish-black tints.

That the film’s apparent coherence of text and image is a construction of cinematic artifice should be obvious, but the film condescends to underline the point. The soundtrack, a plaintive sax solo, twice jars incongruously with footage of musicians playing visibly different tunes, prompting suspicion of any facile congruence between events and their remains in the picture world. And in a sequence quite exceeding the credulity that associative editing might sustain, a funeral procession plods down conspicuously non-Mexican (i.e. Toronto’s) streets, a near-parodic intrusion that must be rationalized as a metaphorical digression on the universality of death, or some such thing. All these contrivances and retractions cumulate in a film whose reliability as documentation is severely undermined by its imperative to simulate fiction. Somewhere Between thus exploits a special tension inherent to the travelogue as a genre. Conventions that would affirm the continuity of narrative films, or the veracity of documentaries, are here destabilized, indeterminate, somewhere between… where, exactly?

Clearly not the poles of a debate concerning the film’s ethics, which it suffered when it was first exhibited in 1984. Its supporters regarded the omission of the child’s death as a noble refusal of spectacular and exploitative documentary practices. Its detractors, conventional ‘journalistic’ documentarians, considered the film irredeemably deprived of the potential impact conferred by such a powerful image.

Both these arguments assume the film’s images support the text, signifying only the conclusive absence it describes. But the latter position does implicitly contain a more incisive interpretation: footage of the accident or its aftermath would confirm that it actually happened. This shopworn raison d’etre of the journalistic documentary finds application here; an appeal to evidence validates the skepticism this film seems designed to provoke. Its issues aren’t ethical but ontological. Did the dead youth exist, or did Hoffman invent him? Given the film’s lack of positive evidence, coupled with its protracted insistence that it be acknowledged as a synthetic construction, the question remains. There are two plausible answers. In the first instance, Hoffman sifts through a large amount of Mexican vacation footage to find a few shots that, by chance, contain imagery similar to details he recalled of the accident and to the text he wrote to describe it. Or he returned from Mexico with a relatively small amount of attractive but disparate, mismatched footage which he united into coherent form by fabricating the accident as a kind of plot device.

Occam’s razor might suggest the second option, but that’s not the rub. As film critic Rita Gonzàlez writes “…international filmmakers have been drawn to the notion of Mexico as a transgressive or mythic space, an eidolon that they have done their part to perpetuate.” [1] As the avant-garde film canon attests, south-of-the border has been a popular destination for filmmaking tourists, the special condition of their alienation in Mexico circumscribed by this imperative to solicit visionary experience. The roster of sojourners include Bruce Baillie, Bruce Conner, Richard Myers and Chick Strand, who made most of her career around Guadalajara and once confidently decared “Mexico is surrealism.” The Mexican travelogue is almost always their projected phantasmata. The ‘reality’ of the death in Somewhere Between is akin to the ‘reality’ of, say, the quintessentially Mexican peyote hallucinations in Larry Jordan’s Triptych In Four Parts: that is, as real as permitted by illusory circumstances. The virtue of Somewhere Between is to be conscious of its complicity in this tradition of cultural mystification. It inspires and permits doubt. It doubts the authenticity of the particular experience it describes, the authenticity of Mexico as an experience of the ‘mythic,’ perhaps ultimately even the authenticity of experience in general. Typical of the traveler’s tale is a tendency to embellish. Rarely is it so evocative, or so obliging, of the tendency to disbelieve its teller.