by Monica Nolan

Indie Circuit, March/April 2004

Category Archives: Films

Living as Filming- Interview (by Barbara Sternberg 2004)

Philip Hoffman interviewed by Barbara Sternberg (2004)

BS : Hi Philip – When I saw What these ashes wanted (which I was almost afraid to see: would it make me cry over our loss of Marian; might I feel you had exploited Marian’s death for a film?), I felt it was your most successful film—most complete, most fulfilled in its methods and purpose. I mean that form and content were synthesized. (Of course, to be reminded of Marian’s liveliness and bravery in life as well as facing death brought sadness.) The film had a looseness, an openness (reduced use of the first-person voice-over, passages of silence, different types of footage and shooting styles, a relaxed episodic structure) that gave Marian, yourself and the audience respectful space. The film breathes, it’s organic-it moves forward, yes, but there are detours, meanderings in its progression. You have always done beautiful camerawork, but I could connect to this shooting and how it figured in the totality of the film more than in any other (Opening Series and Chimera have shooting I also love and seem to mark a change in approach). After the film I came home thinking how all your films carry forth certain inter-related themes: autobiography (film as constructed memory) which has been constantly examined since your first film On the Pond; the ethics of filming, most clearly stated as problematic in Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion; and death. The fear I had had of exploitation, a question of ethics, was addressed in the film’s dialogue:

PICTURE: SILOUETTE OF MARIAN ON HOSPITAL CURTAIN

MARIAN: …if you could have a ritual for death what would it be…and would it be private or shared.

PHIL: ..I think it would be shared.

CAMERA TILTS TO MARIAN’S EYES…THEN TO THE LIGHT

Opening Series dealt with authorial control, an ethical problem for you, by handing over the sequential ordering of its parts to the audience and to chance. I remember you’ saying, “Why should I have total control?” (One might also think of new music’s compositional principles of indeterminancy and chance.) The choice of order of the rolls gave an element of random chance and loosened the strength of narrative line.

PH : It was also to create a space where the audience, myself and the work could come together and manifest something. Each screening would be different not just because of the order of the work, but the order would reflect its audience. For example, I had shot some footage in Egypt of this Dutch companion that we met along the way who was filming Berber people holding up their tools and crafts. My filming of him, filming the Berber man, became kind of a critique because I included the photographer in the shot. That was shown at an event where he was present in Holland. So, not only did this become an issue when we discussed it after the screening, but there was also some kind of psychic manifestation that happened in the ordering. The way the other elements proceeded and followed this problematic image forced a particular reading of the situation. This was quite surprising. It’s like divining with the I-Ching. So, in Opening Series I was also trying to deal with these sort of invisible links between people, objects, in and out of art making.

BS : In Ashes you make editing choices and yet retain an openness. Space. This new openness is not only a strateg, but a place from which to make a journey, a film. (Is there a difference for you? Is living filming and vice versa? )

PH : I approach every film differently, so I’m not sure the next one will have the same kind of openness, though I think this is something that I have been developing since the early 90’s in films likeOpening Series (1992-95), Chimera (1996), Kokoro is for Heart (1999), and most recently What these ashes wanted (2001) I suppose there is not the same need to say things so overtly as in ?O,Zoo! (The Making of a Fiction Film) (1986), or in some of the collaborations I made in the 90’s where it seemed the process of collaboration and its outcome was more important than developing my own voice in the way I did in the ` looser films mentioned above. The 90’s for me was a time to try different ways of working but the most common element was collaboration, whether it be an aleatory collaboration with the audience who helped to place Opening Series in an order, or my `directorial’ collaborations with Wayne Salazar in Destroying Angel (1998), Sami van Ingen in Sweep (1995) or Gerry Shikatani inKokoro is for Heart.

BS : The story (made up? I had assumed) of film kept in the freezer, unprocessed in ?O, Zoo! is told again, in What these ashes wanted, but this version and this time, it’s true – right? In Somewhere Between Jalostotitlan and Encarnacion (1984) you questioned your right to film the death of a Mexican youth—at least text over a black screen told us this seemingly true story.

On the road dead lies a Mexican youth

I put the camera down…’

(excerpt of text from Somewhere Between)

In “…Ashes…” you say that just before Marian died you two slipped out of the hospital at night down to the lake’s edge, and here’s the photo of the lake you took.

I took a picture, you skipped a stone

(excerpt of text from What these ashes wanted)

But just prior to this we see a similar scene from a TV soap opera! Ethics, authority of the filmmaker, veracity, credulity, autobiography… So much of your filmmaking and teaching favors personal story-telling and yet you question both the ethics of film and the possibility of truth. Where does Ashes stand in relation to these terms and in relation to your previous films—and where do you think you place the viewer?

PH : The fallen elephant story in ?O,Zoo!, in which I film a dying elephant and then feel badly about filming it, exploiting the elephant for this sensationalistic act, and subsequently I put the film in the freezer—is a metaphor for what actually happened in my youth as the family photographer, when I filmed my grandfather in the casket at the request of my uncle. Subsequently, in horror at what I had done, I put the film in the freezer. I think when I wrote the story for ?O,Zoo! in 1986 I didn’t realise that unconsciously I was expressing this repressed traumatic experience. I found it quite curious that I had written a fiction, that had its source in a true story, which had happened, but that I didn’t know I was creating a stand-in for this difficult experience. The unconscious was pulling at my shirtsleeve, saying look here, remember this.

In Ashes, the Baywatch scene at the beginning of Part 3 mirrors the personal story of Marian and I leaving the hospital the night she found out she had cancer. The TV soap represents the way, through mass media, our culture presents grieving. Ashes offers another method. Some of Marian’s last writings, which I cherish, came after our final walk on the beach. She wrote in a way that told me that this was not just for her, but the writing should be passed on. In her grief, she had found out something that night and was offering it up. I was the one who could release it to the world through film.

TEXT ON SCREEN (black text supered over window):

The night we had our last walk

she wrote these words:

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

We come together separate

cry and look wide eyed bewildered…

I want to be near the water

We bundle up and leave the hospital for the beach

Beautiful clear crisp blue skied night

we mourn together

laughing at intervals

clinging madly to some sense of life

The open sky water makes me feel

part of something immeasurable

larger than me

and it is consoling

STILL PHOTOS OF MARIAN’S ROOM

(excerpt of text from What these ashes wanted)

So in a way, my films blend fiction with real life experience, and the fiction is usually grounded in lived experience. My sense is that once these expressions are mediated through the filmmaking, they are fictions anyway. I feel fine with this as long as what is made up is somehow a reflection of, or is based on, or comes out of a lived experience-which usually happens naturally. I try to let the experience of filming or photographing or recording audio, happen out of an authentic process of trying to find something out, or communicating something to someone. The residue of this process finds its way into my films.

I think Somewhere Between and ?O,Zoo! are dealing with ethics, but the starting points were traumatic moments that occurred while filming. I feel my calling is a filmer of life. A death occurs in front of me so I have to do something about the experience. During the filming of Somewhere Between I remember sitting on the bus with the camera on my lap, feeling the whole horrible experience. I chose not to film, perhaps more as a gut reaction, but when I returned to Toronto the aura of the boy’s death laid over me like a blanket. I wanted to still make a film about this sacred moment, which I had witnessed, without the so-called crucial image.

reaching out,

the white sheet is pulled over the dead boy’s body

the children wept…

the little girl

with big eyes,

waits by her dead brother

big trucks spit black smoke

clouds hung

the boy’s spirit left through its blue

(excerpts of text from Somewhere Between)

BS : So, in a way, all your films exist to have the audience at some moment wonder: what is truth? What is fiction? What is film? Is this truth? All of those things are floating around. As audience we go in and out of being sucked into the film the way mainstream films tend to operate on us, and then we’re conscious that this is a construct, that there are certain clues within it that make us say, Wait a minute… and give space to interact with the film. Reality is the interaction between us and this thing you’ve put out called a film.

PH : You asked me earlier if I brought the camera to the hospital to film Marian. The answer to this question expresses something of how I work, of my process. Marian was in the hospital. It was the fall of 1996, `the days of protest,’ and she was mad as hell at the Harris government and all the cuts that were occurring to the social programs. This also effected her directly `on the floor’ in the hospital she was in. She was trying to write a story about all this and she was taking pictures of herself in the hospital.

After Marian’s death, I developed the roll she had taken in the hospital, and found this picture of her, in silouette. She took it of herself in silhouette against the hospital curtain. She also filmed the same curtain from the same angle, and left herself out. Blank. The picture made me shudder. Most often, the powerful personal images, which I use in my films, have had other purposes.

Sometimes I do find it necessary to ask family or friends if I can use a particularly `personal’ recording. In an earlier work, passing through/torn formations (1988), there is a sequence about my uncle and his daughter, who had not seen each other for sixteen years. I met him in his pool hall hangout and told him his daughter wanted to see him. He said he’d flip if he saw her so instead he gave her a present. I followed him into the drugstore and he found this mirror that was in two parts, that folded into itself – a ‘corner mirror’ he called it. He felt it showed you the ‘real’ reflection of yourself, ‘the real you.’ It technically does this since it is constructed as two separate parts, the image of yourself, though severed, reflects into itself, thereby rendering your portrait normal, like a photograph. Your face isn’t reversed in the way a normal mirror reverses your features. In exchange for the corner mirror his daughter wanted to send her father a recording, so I taped her message to him. It was my idea to also tape her looking into the ‘corner mirror,’ describing her own facial features. I found him again, and we listened to it in my car. He was deeply moved. A few years later when I was finishing the film I asked her if I could use her voice from the recording and the film we shot of her looking into the corner mirror, and she agreed. As for my uncle, we spent some evenings looking at different cuts of the film, while he played music to it. I used his music in the film. Later I showed him parts of the finished film, though he was most interested in the music. I had thought the film could be a vehicle for me to get to know my uncle again, who used to take me fishing and teach me accordion when I was young. I guess it did somewhat, but it was a bit romantic on my part because film can only do so much. Anyway, I find that this kind of material works well for me as it rings true. It is the residue of lived experience which I can best learn through. When I start imagining something that I should film, and then I carry it out, it often seems contrived and it’s often not as useful as working with what comes along spontaneously.

BS : When I used to be the photographer for a friend’s wedding or anything like that, it kept me at a remove, this in-between space of the camera, between the event and me.

PH : It is the event. Everyone is using images, looking at pictures and video. It’s not once removed, and it is as authentic a moment as any other. The question is how to position it within your experience.

BS : It’s how you interact.

PH : It’s how our culture interacts.

BS: Your first film On the Pond (1978) starts out with you and your family looking at family slides, and on the soundtrack we hear your family commenting and reacting.

PH: Yes, to me this is a continuation of an oral tradition I learned from Babji, my grandma. She would talk to us about our dreams at the breakfast table. The difference is I use a tape recorder and transport conversations through my films.

BS: I want to go back to the term “autobiography”. You’ve made a home movie, a road-movie, a making-of-the-movie movie. I guess your films are autobiographical in that they represent the truth of how it is for you, subconsciously, psychically, spiritually, as well as materially. Do you feel the term autobiography is applicable to you?

PH : I don’t use it much because autobiography assumes that it’s just about yourself. My films are about people and places around me, though strained through my perception. When a writer uses material from their life in a novel, we do not call the book an autobiography. I suppose we might say there are autobiographical elements in the work, but that is common with most art. It is only that the photographic or electronic image is a good stand-in for the real, so we cannot get around the fact that people depicted in a `documentary’ are actually and fully ‘on the screen!’ But we know it’s still an expression or reflection of the person, of the originating moment. Films are constructions, and in my work I construct characters out of the residue of real life experiences.

BS : As Godard says: Film is truth at 24 frames per second, all film is fiction. Do you think the focus on death in your work is because of your personal experiences with your grandmother and Marian?

PH : Everyone experiences a death close at hand but not all filmmakers deal with death so directly, or so often. Maybe it was this initial experience filming my Grandfather in the casket. You know we spend our lives working through this mess…. whether it be a difficult birthing or a difficult family relationship. I’ve said before that childhood is so traumatic, most of us sleep through it… maybe the next part of that statement is that we spend the rest of our time consciously or unconsciously shedding this inevitable pain. I’m glad I have filmmaking because it seems to be a good place to put all this stuff. Maybe I was marked by that experience and I have to keep pushing the rock up the hill—my karma?

BS : Do you think it has something to do with your Catholic upbringing (we saw you at your first Holy Communion in both On the Pond and Kitchener/Berlin)?

PH : What I think my Catholic upbringing taught me was that bread can turn into body and wine can turn into blood. The material and the invisible (spiritual?) are interchangeable, certainly one isn’t more important than the other. My films, like many experimental films, take on a form that honors what we can’t see with our eyes. I work with the photographic image, this art that can represent real material objects/beings most precisely, but eventually my intent is to shed light on the things we can’t see.

BS : …or your German ancestry? The reason I mention the German ancestry is because a couple of times, in passing, you’ve made a comment to me about your name Hoffman, and that the name Hoffman is German… and I thought, perhaps, you were saying it to me because of my Jewish background.

PH : Right.

BS : And that was a link between us to that history.

PH : Yeah.

BS : And what to do with that? The burden of that history.

PH : Yeah. Yeah.

BS : So, the reason I mention it here is because, certainly recent past German ancestry calls up the Holocaust, and the Nazi period. I don’t know if that’s on your mind at all, as a burden.

PH : Well, it’s in passing through. It’s easier to deal with on my mom’s side, which is Polish—the occupation her family experienced in their homeland by the Germans. There are two stories in passing through, but it’s not dealt with directly, only as a part of the family’s shared history. I also have some old 1/2 “tapes of my German grandma looking at photos from her past and talking, so they may be a vehicle to deal more deeply with this subject.

BS : Films to come?

PH : Maybe.

BS : Are the encounters with death the catalyst for making the films? I recall Bruce Elder pointing out (in a class he was teaching) how Michelangelo Antonioni’s protagonists are separated from others and the flow of daily life by an encounter with death which gives them a different awareness.

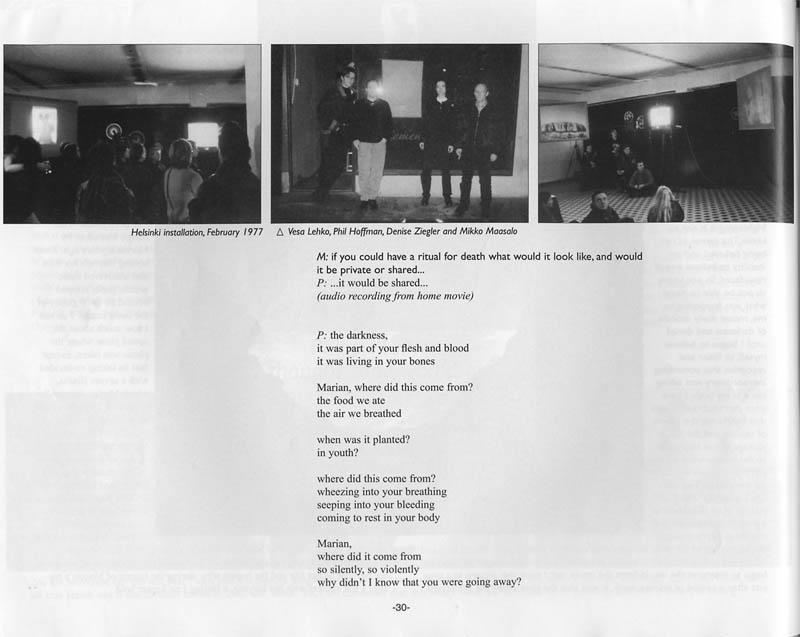

PH : When the death of a loved one occurs you do go into a different space, and I did film some moments within that space after Marian passed away. However, I am not only in a movie, I’m also looking at my own experience from the outside as I construct the film. Certainly as time passed, my own state changed. As I make my films I’m dealing with people directly, my filmmaking is social, I’m sharing it with the world. I’m making this work and I’m showing an installation of it in Finland and Sydney. I’m not separated from the culture, I’m embracing it, trying to find a ritual to deal with death which makes sense to me, and I hope others. This makes more sense to me than the funeral parlor, the casket, and going into a room with all the flowers and everyone afraid to say anything.

BS : I remember at Marian’s memorial service. I was really enriched, and felt I had gained so much from it. But my initial reaction when you showed a film during the memorial was, I was taken aback. I thought, he’s showing a film at her memorial?! But by the end of the whole service, with everyone contributing in their own way, I felt that I had been enriched, and educated, and moved.

Ph : Well, I felt it was the only thing I could give because I couldn’t talk. It was just a poem about her first coming to the farm, and a kiss.

BS : With Opening Series and Chimera and now Ashes your shooting has changed. The camera is much less stable, more fluid and animated with shorter takes. Where did this come from? Do these signal filmic and/or philosophical developments?

Ph : I started shooting in short bursts in Chimera (and in some sequences of Ashes) around the time the wall was coming down in Eastern Europe, and the Internet was going up everywhere. My drive to fragment came from a perception that something was breaking down…well so was my reliance on the photographic image as document, as opposed to expression. I think in Ashes I maintain a better balance between these two aspects which I hold a high regard for. When free association becomes the mode of perception, which is the only sensible tool when so much is up in the air, making a mosaic film is more apt to navigate this space we live in, as opposed to the page-turning form of linear narrative. You’ve also been working in this way, evoking a kind of present-ness…

BS : With presence. When I started shooting in short bursts and single frame it was to achieve a simultaneity of place and time I think of as reality, a relatedness, which I had approached in earlier films by superimposition. Now I was trying ‘editing’ closer and closer bits. It also came from a view of myself/filmmaker as observer rather than master or in control.

PH : There have been some great developments in this kind of work, like Brakhage. Trying to develop a spiritual space for living/filming in` the now. I love his film Black Ice and the Arabic Series, and in your work I love the present-ness in Like a Dream that Vanishes. As a viewer we’re not thinking about what has happened, or what might happen. We’re right in the moment.

BS : Part of my thinking about that was if you get past the identification of what the image is, or what the narrative information of that image is, then you can get closer to a sense of being.

PH : And the flow of time.

BS : Yes, yes. That it keeps going, and you can’t stop it and hold it, and study it.

PH : “Time goes…” as Aunt Katie says in one story in Ashes. In Like a Dream that Vanishes you break it up with observations of the philosopher, John Davis, who you filmed. I think it really works, because you weave these rushing images throughout, and then we’re back listening to him talk about the `mess’ of experience…and of course we realise it’s a mess because it can’t be controlled….because living in the present is the roller coaster you can’t control.

BS : This way of shooting and making allows the complexity and wonder in. I’ve been thinking of the structure of Ashes which is more episodic than earlier works. Sequences sometimes have a loose connection, (besides being different shooting styles), but aren’t firmly attached to the preceding one. The connection isn’t justified with causality, although they seem to belong. Some were little detours and gave a bit of relief from the story of Marian’s passing. Like the Egyptian interlude. The sequences stood on their own, and yet they seemed to fit together into a whole. I felt there was a whole-ness to it, despite the fact the sequences could be quite independent. I’m wondering how you determined the structure, how you selected what to put in, and how you ordered it?

PH : It was a long and organic process that started in 1989. I was shooting single frames—zooming on each exposure to create a splayed image There were a number of projects that came out of this way of shooting: Opening Series, Chimera, and some installation works. When you are shooting without a plan, just collecting images from your life, there tends to be an organic connection between life and work.

BS : There is a unity in all your work, because you’re you.

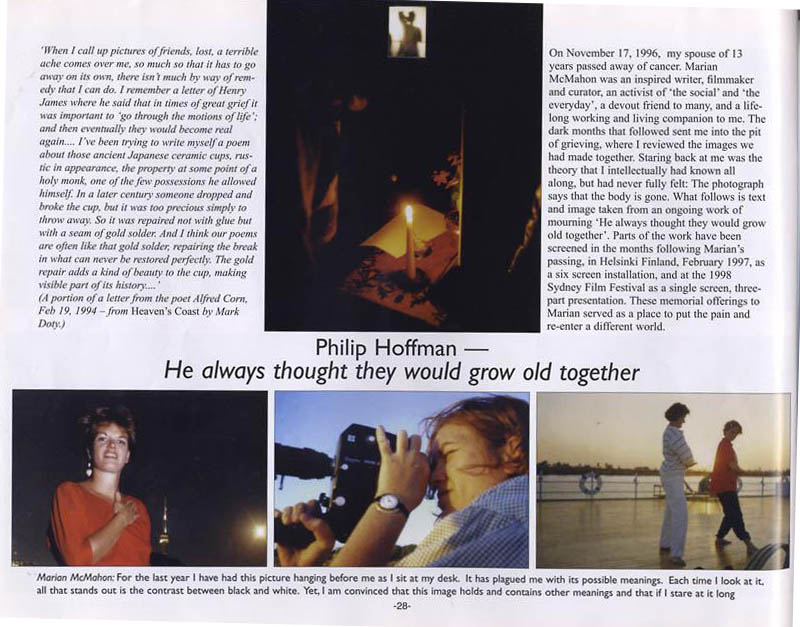

PH : Rather than because it’s a project you are working on. As the 90’s moved along, I started working on Destroying Angel with Wayne Salazar, which Marian assisted through her talks (and recordings) with Wayne. Suddenly in the middle of it Marian tragically died. After a time, Wayne, who had a strong connection to Marian, asked me if we could use some of Marian’s story in our film, which I agreed to. At the same time, I had been asked to construct an installation in Finland. When Marian passed away, I felt I couldn’t really make the trip, but my friends there called me up and suggested I come, they’d take care of me. Since I was spending so much time going through all of the images we had together over our life, why not create something out of it? It seemed to be a positive space for me, so my friends in Helsinki helped me make a kind of offering to her, a six screen circular work, in which many of the ideas for What these ashes wanted developed. My process of finding the structure for Ashescame out of these projects which I was immersed in after Marian’s death. It just seemed to be the way I wanted to spend this grieving time. At the beginning of Ashes, there is a recording from my answering machine from Mike Hoolboom, who gracefully relays to me a story about the repairing of a precious piece of pottery, and I thought that I was trying to do the same thing with the film, with my life. To show something of beauty from a life that had been shattered through her death.

HOME MOVIE (SLOWED DOWN) OF A WOMAN (MARIAN) WALKING PAST COLUMNS IN FRONT OF EGYPTIAN MONUMENT

SOUND (TELEPHONE ANSWERING MACHINE):

MIKE: Hi Phil, I found this in a book and thought you might like to hear it, hear goes.

When I call up pictures of friends, lost, a terrible ache comes over me, so much so that it has to go away on its own, there isn’t much by way of remedy that I can do. I remember a letter of Henry James where he said that in times of great grief it was important to ‘go through the motions of life’; and then eventually they would become real again…. I’ve been trying to write myself a poem about those ancient Japanese ceramic cups, rustic in appearance, the property at some point of a holy monk, one of the few possessions he allowed himself. In a later century someone dropped and broke the cup, but it was too precious simply to throw away. So it was repaired not with glue but with a seam of gold solder. And I think our poems are often like that gold solder, repairing the break in what can never be restored perfectly. The gold repair adds a kind of beauty to the cup, making visible part of its history….

(Taken from a portion of a letter from the poet Alfred Corn, Feb 19, 1994 from the novel Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty.)

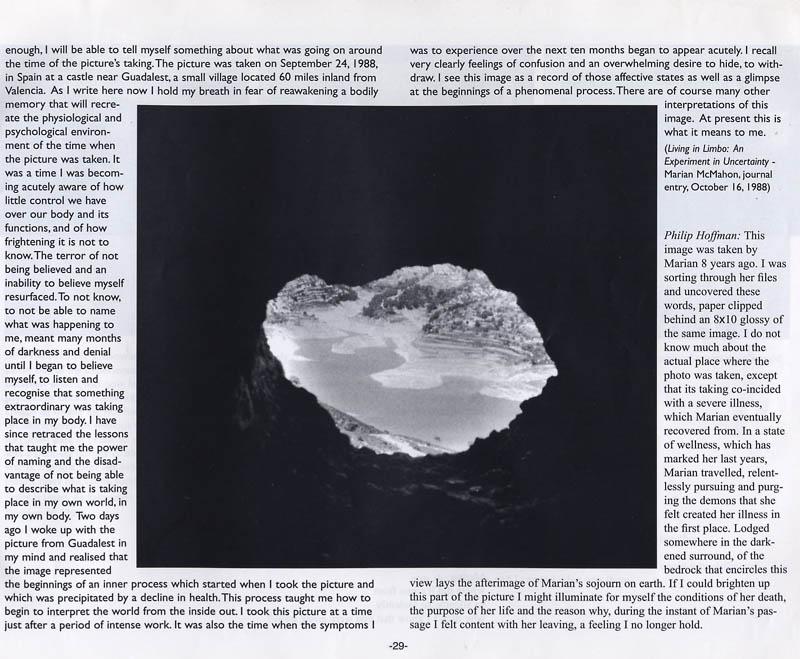

OK I guess that’s it. See you later.

At times I think this could come off as crude, using filmmaking as a process for grieving but felt it was a way of honoring her. I went to Spain to try to find the rock opening which is seen at the start of the film, with her text superimposed, where she realizes her illness. I found this text paper clipped behind a still image of this hole, which seemed to be a cave in Guadelest, Spain. I journeyed there with her friend Belinda and we had great trouble finding it. I felt they must have removed it some how, until I looked down on the ground and saw this tiny opening, exactly the same shape as the photograph she took. We had a laugh imagining her down on her stomach trying to take this picture.

The film’s structure came after Marian’s death when I was spending this time remembering her, and bringing this film work around to friends and strangers.

BS : There was one sequence in the film, where you’re in the back seat of the car taping Marian while she works as a nurse visiting people’s homes. I thought it was a very interesting scene for its mixture of realities. Marian’s a nurse, she’s going into people’s homes, and yet this is being filmed, so is this staged for the film? No, this is real, and we’re seeing it being filmed. This scene sets up the whole question of veracity, what is real and where is the real located?

PH : Yes, that’s the synch scene where I sit in the car with this huge 3/4 inch camera, circa 1983, filming her reactions to what she has just seen on a particular home visit. She was giving up nursing so she asked me to videotape her on her last day on the job.

BS : At one point, as I recall, Marian chastises you, or gets mad at you, because you’re not answering her question.

PH : Mike Cartmell remarked that what is strong about the film is that it honors not always only her good side. You know, she was a pretty tough cookie. And it doesn’t show her necessarily in the best light, which of course, is the best light, because it was part of her. I’m in, probably, my late-twenties, and I’m saying. Yea it’s hard, the camera’s heavy. And she says, that’s not what I mean, it’s hard emotionally. It’s hard for me to be filmed, and she chastises me, and in a funny way, makes fun of me.

BS : And leaving this in gets more at this question of, where is the real in a situation? She’s saying that you answered in a superficial way. It’s an awkward situation because the camera is heavy, but she was trying to get at something below the surface. I think it’s very typical not only of your process of filming, but of Marian’s whole project of digging beneath the surface. How do we come to knowledge? What forms our sense of what’s real and true? This episode functioned on a lot of levels. I’m wondering how you see this scene functioning in the film.

PH : Well, it introduces her ‘in the flesh,’ because it’s sync sound. One of the ways that I want to represent her is as a physical being, closer to, let’s say, a realist representation of her.

BS : So it’s Marian. But its also any of us, in a sense. I mean, the film is about you and Marian, and what happened, but what if I don’t know Marian?

PH : If you didn’t know Marian, now you actually see her in the flesh. So it’s serving this purpose in the film… you are introduced to the loved one who has been lost. This is why I like to blend various forms, for example, synch sound with a more impressionistic sequence. These are different aspects of how we perceive.

But I think the purpose of this scene coming at the beginning of the film is so that there is ground to stand on for the rest of the film. We are introduced to this person in this way, twice. She comes back again, `in the flesh,’ in synch-sound talking in front of the palm trees, and again she is questioning, but mostly I like that scene because we can see her mind working…..she is constantly discovering something for the camera, which brings her to life for a brief moment.

BS : And it would seem that the process of making a film is the questioning part of the experience for you.

PH : Yeah that’s right.

BS : We’ve talked about Chimera in terms of it having been a film in three parts, and used in an installation, and now parts of it finding its way into Ashes. I just wondered how you saw that footage functioning in this film.

PH : Well, the single frame zoom footage is carried forward into Ashes, because it carries the three deaths that occurred when I was filming that way. In the early 90’s, three times death came in front of me. This occurred in 1991, 1993, and 1994. I found it strange that this kept happening, and that it was always connected to my filming. I brought these stories and this shooting forward into Ashes, because they seem to serve as a kind of premonition of death, and though one cannot really be ‘prepared’ for the death of a loved one, it seemed to make me aware that something was coming. I am troubled by these thoughts because two people died, and one nearly, which is horrific and sad. I still do not have an explanation for this so it sits in the film unresolved, like so many things in our lives….

BS : The style of that shooting, for me, points to the ephemerality of life. Each second is over, it’s not something we can hold in our hand. Whereas a still photograph gives you the illusion of having something, but really you have something out of time, and so very death-like, whereas this is alive, this is present, and yet you can’t have it.

PH : Now you see it, now you don’t. It is like that.

BS : There’s also image-to-image speed, because it’s not a single image that you zoom into and out of.

PH : Past, present and future exist at the same time, which is maybe what death is, or what happens after death. There is no form, no linear time.

BS : I also want to talk about the slow motion sequences.

PH : The first part of the film is book-ended by a shot of Marian running in slow motion, first in colour, then in black and white. As if she keeps fading, but is also eternally returning. These are representations of the dream space one is in when one has psychic trauma. She did keep coming back in dreams, or in waking life, or absurdly through the ladybug form. Just like a photograph which actually reminds me that she is gone. It is often said that photos, films or sound recordings help us to understand the past. Well, I think they also help us get through the present. Diving into this kind of footage after Marian’s passing seemed a good place for me to be.

BS : Between teaching at Sheridan College and now York University and at the Film Farm workshop, are you creating a movement within experimental film with a manifesto or credo that you espouse?

PH : I try to create a place where people can meet and be together. If it’s a movement it’s a movement of sympathy towards each other, or a place to be, where people are working together instead of tearing each other apart.

BS : Competing.

PH : Competing, or spending so much money to make a film. A place where making something is the most important thing. So I wouldn’t say that is a manifesto, but it is a place where I feel right. The farm workshop is set up so that people need to be there for the whole time, so it’s a retreat. They need to come without a script, and part of the idea is that there is a film inside and no matter where they are, it can be coaxed out. In the time they spend at the workshop they can make a start on that, or finish it, wherever they end up at the end of their stay. Participants learn certain processes, working with a Bolex, with light, with hand processing and tinting and toning. They don’t have to worry about getting it exactly right, sometimes the accidents help them find their route. It’s a bit like cooking, tasting what you’ve done, adding a few more spices here and there.

BS : I thought we could call this interview “Man with a Movie Camera” and use the photo of your silhouetted torso with swinging arm suspended by a Bolex-holding hand. I think you’ve had an image of you-with-camera in every film you’ve made. Is this honesty (this film is made by someone, it’s not objective truth) or autobiography (and that someone is me)? Is your life lived through making a film of it?

PH : Isn’t it something like a signature? Though this moves against the idea of giving up authorial control. But I think there is something important for me about being able to see where I’ve been through my films, and my life, and the people who have taught me things.

What these ashes wanted (Script)

by Philip Hoffman

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black)

What these ashes wanted, I felt sure,

was not containment but participation.

Not an enclosure of memory,

but the world. ‑ Mark Doty

HOME MOVIE (COLOR) OF A WOMAN (M) AND MAN (P) AT A SCHOOLHOUSE…PLAYING IT UP TO THE CAMERA IN HOME MOVIE STYLE

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

What these ashes wanted

MAN’S HANDS (P) ATTEMPTING TO PUT BROKEN POTTERY BACK TOGETHER – CUT VERY RAPIDLY (COLOR)

HOME MOVIE (SLOWED DOWN) OF A WOMAN (M) WALKING PAST COLUMNS IN FRONT OF EGYPTIAN MONUMENT

SOUND (TELEPHONE ANSWERING MACHINE):

MIKE: Hi Phil, I found this in a book and thought you might like to hear it, hear goes…

When I call up pictures of friends, lost, a terrible ache comes over me, so much so that it has to go away on its own, there isn’t much by way of remedy that I can do. I remember a letter of Henry James where he said that in times of great grief it was important to `go through the motions of life’; and then eventually they would become real again…. I’ve been trying to write myself a poem about those ancient Japanese ceramic cups, rustic in appearance, the property at some point of a holy monk, one of the few possessions he allowed himself. In a later century someone dropped and broke the cup, but it was too precious simply to throw away. So it was repaired not with glue but with a seam of gold solder. And I think our poems are often like that gold solder, repairing the break in what can never be restored perfectly. The gold repair adds a kind of beauty to the cup, making visible part of its history….

(Taken from a portion of a letter from the poet Alfred Corn, Feb 19, 1994 ‑ from Heaven’s Coast by Mark Doty.)

Ok I guess that’s it …see you later…

VISITING NURSE (M) ON DAILY CALLS, SHOT FROM BACK SEAT OF CAR BY (P).

M- It’s almost as if I’m experiencing the stress of the contradiction. A stranger going into someone’s home, touching their bodies and you don’t know what their name is. Going into your private part of your life experiences but you’re body is public property and it’s being treated by the medical profession. That to me is very strange. 253, Christ… (LOOKING FOR HOUSE ADDRESS).

M LEAVES CAR. DOG WALKS ACROSS ROAD. BOY `DIRECTS’ CONCERT ON FRONT PORCH. M RETURNS. DRIVING CONTINUES.

M- You can’t even go to the bathroom there’s just so much junk around. I go into the bathroom, and there’s a pair of poopy underwear soaking in the sink . Where am I going to wash my hands? I kind of run my fingers under the tap and wet them.

M- A camera isn’t human but it performs the same kind of act…. except it’s not working on my physical experience, but on my psychological experience.

P- it’s working on my physical experience.

M LEAVES CAR. M COMES BACK. DRIVING CONTINUES.

M- 57, 57, 74… 57. Bingo. Okay, see you in a minute….bye…(SHE GESTURES AT P BEHIND CAMERA) …Philip kiss me (laugh).

M LEAVES CAR. M RETURNS TO CAR

M- It’s really hard for me to do this. I feel like I have to entertain you. That’s not what I really mean to say.

P- It’s forcing you.

M- I feel like I ‘m not really talking about things that I’d want to talk about, things that I’d want to talk about with you.

P- Yeah, because you are talking to the camera.

M- Yeah.

P- Well, it’s hard for me, too.

M- Maybe, we should have somebody filming us. Someone

filming you filming me. Why is it hard for you?

P- It’s hard.

M- Because it’s heavy!

P- Yeah.

M- Oh, Philip, here I am talking about psychological difficulties and you’re talking about physical ones. You’re nuts, you really are nuts. Sometimes I think you are so insensitive, honestly.

P- What I’m saying is I’m concentrating on this which makes me not able to concentrate on what you’re saying or interact…

M- That’s a little different than saying that it’s hard for me because the camera is heavy. It’s a little different, you know? Do you understand the difference?

M LIGHTS UP A SMOKE AND STARES OUT THE FRONT WINDOW

TEXT ON SCREEN (White on Black):

He always thought they would grow old together

DISSOLVE TO

PHOTO OF SEASCAPE SEEN FROM A DARK CAVE (GUADALEST, SPAIN)

TEXT ON SCREEN – (black text superimposed on photo seascape):

I found this photograph

which she took 8 years ago

it was in her desk

paperclipped behind this text:

TEXT ON SCREEN – SUPERIMPOSED BELOW CAVE OPENING (white on black):

For the last year I have had this picture hanging before me as I sit at my desk. It has plagued me with its possible meanings. I was convinced that this image held and contained meanings and that if I stared long enough, they would tell me something about events around the time of the picture’s taking. I took this picture on September 24, 1988, in Spain at a castle near Guadalest, a small village located 60 miles inland from Valencia. As I write here now I hold my breath in fear of reawakening a bodily memory of that time. It was a time when I had begun to relax after a period of intense work. Simultaneously, the symptoms I was about to experience over the next ten months began to appear acutely. I began to become intensely aware of how little control we have over our body and its functions, of how frightening it is not to know. I came to experience, once again, the terror – of not being believed and hence, not being able to believe myself. There were many months of darkness and denial until I began to believe myself, to listen and recognise that something extraordinary was taking place in my body. I have since retraced the lessons that taught me the power of naming – more evidence of the logocentric universe we inhabit – and the disadvantage of not being able to describe what is taking place in my own world, in my own body.

Two days ago I awoke, realising that the picture of Guadalest represented the start of an inner process. This process taught me how to begin to interpret the world from the inside out. I see this image as a record of the affective states of that time, of the confusion, the desire to hide, as well as a glimpse at a phenomenal process, that I will attempt to expand through my writing.

CAVE IMAGE CONTINUES

TEXT ON SCREEN – (black text superimposed on photo seascape):

I do not know much about

the actual place where the photo was taken

but that its taking coincided with a severe illness

which we thought she recovered from.

In a state of wellness which marked her last years

she travelled and purged the things she felt

created her illness in the first place.

Lodged somewhere in this darkened surround

lays her afterimage.

If I could brighten up this part of the picture

I might illuminate

the conditions of her death

the mystery of her life

and the reasons why

at the instant of her passage

I felt content with her leaving

a feeling I no longer hold.

M AND P WALKING IN THE SNOW…KISS (COLOR)

HI-CON B&W AND HANDPROCESSED IMAGES

SOUND: MUSIC/SOUNDSCAPE, TELEPHONE MESSAGES DESCRIBING FLOW OF A LIFE:

…and thanks……if you could get in touch with us, and

just wondering how you fellas are getting on, haven’t heard from you in some time, bye for now

its not far out of reach at all….this number is…

This is the culture Lab at Toronto General confirming your appointment for Monday, January 23 at 10:10. If you are unable to attend, please call 310 404-0216… Please remember to bring your Hospital Health Card. Thank-you

…I can offer an alternative situation. If you would like to ring Betty Litkey…. Betty and I’ve worked together in this office, and she’d be able to give you answers to your questions. Thank you so much, good-bye. The time is ten o-clock…in the morning, I’ll try to get you by 1 o’clock this afternoon, and I’ll try again before five.

…Parallelogram, Students Against Censorship, This Ain’t The Rosedale Library, if you could please call me that would be excellent… Just calling to say hi and whether you want to put up posters before the meeting, or…anyway

Okay, see you. Hope you had a good day, bye….

Yeah, Arrow does a little nervous yawn during that, when you give your message… that’s quite nice…Anyway, It’s four o’clock, I’m going into class.

Honey I love you, bye.

Marian. I’m thinking about our paper here alot, and I’m…one of the things we didn’t talk about was… schooling as a site of depravation. Would you mind calling me? Bye.

…looks like you got did rid of the fire alarm…and what are we thinking about…

I was wondering if you come and stay with me, sleep over.

Good-bye, love ya….I survived last Wednesday….tried to phone you, um…

Marian…

thank you, can you come in Friday? 10 am tomorrow. That’s Friday…

…your application seems to have gone awry, I tried to call you at half past ten this morning, don’t know whether your bringing it back or whether… I’ve been trying to get a hold of your lawyer, he’s not there. He’s in Palmerston, so I don’t know if you set up anything with him….I’m at the office… here in Flesherton… I’ve been across to Mt Forest and the offer is now with the vendors, so I’ll get in touch with you tomorrow and let you know how it goes.

I got your name and want to organize some kind of benefit for Danica House, if you could give me a call back, I would really appreciate that.

Hello? Hello, hello this is Denise…Oh hi, hi Denise

I’m calling to say your drum is ready…Hi….

I felt like I… I hung on to your stone very tightly. ..Oh, good.

I felt like I… I talked to my mother in ways that I wanted to….

It’s Saturday night and I just remembered that you said you’d be in Toronto. Just called to say…

…my blood test is back, so give me a call, bye…ok. Love you both, bye now, happy new year.

The short message is…it’s a girl! Talk to you later

…Done…we’re $84.00 over-budget that’s about … the bill is five hundred…

…calling from London, it’s about the article for Feminist Review

I wondered if you got my letter….thought you’d be able to do the changes in time for this issue? Just wondering how you’re getting on?

Mr. Hoffman?

He’s not here, can I take a message?

Is this Mrs. or…?

No, there is no Mrs. Hoffman.

Are you a daughter or….

Hi, it’s me, um

Phil…Phil…it’s a girl …we’re so happy…

..whatever is convenient. take care, bye, bye

I love you, bye

I got your card from Amsterdam … it’s a riot

had a great time … come to your place… I want to talk to you, I’d love…

Friday

I should be passing through Toronto with a bloody quick transfer … arriving from Halifax at Pearson Airport at 12…Heathrow at…1700 hours….

What are you doing tomorrow night? I thought I’d make dinner

…Is acceptable… well, it has been widely unacceptable in the academy

…I might go…I wanted to speak with you about the proposal.

we haven’t got any wood …. you know…

what happened….

yeah… well, my mother…..

it’s me again

drive me to the show

I don’t know what else to say…but I want to you to be home

…okay, hope you had a good day, bye, bye

COLOR IMAGES IN GARDEN AND AROUND STONE HOUSE

Hello. Will you please call Wilma Rouse at 323-3429. I still have a blouse here that I don’t know what to do with. Thank you.

…Oh, Good…Its hard to…. Its really hard to…Its about 3:34, and um…

Are you there? I was wondering where you were? It’s me…

I won a competition…and

I don’t know where you’re going to be. Anyway, I’ll call you

… Here’s a very short message from a really long way away…. I just called to say that I miss you, and I wanted to hear your voice, but I didn’t hear much of it… ok, bye.

I’ll call again… I’ll talk to you later on tonight. I think I’ll call you later tonight, ok? Bye.

I don’t know what else to say?

…but I want you to be home.

I hope you’re well…

I keep trying to get a hold…

I was wondering where you were?

How did it go?

It went, it went well.

Yeah?

…Or give me a call before…. I’m making dinner.

People said things to one another…like they hadn’t done before…

….I just called to say thanks for the weekend…..

…a nice tropical island….

LADYBUG MOVES SLOWLY ACROSS LEAF OF PLANT

IN SLOW MOTION (B&W HI-CON FILM) WOMAN (M) DANCES PLAYFULLY… OFF IN THE DISTANCE SPINNING AND LAUGHING DISSIPATING INTO THE SNOW… CLEAR WHITE SCREEN…DUST

LADYBUGS CRAWL AROUND HEART-SHAPED PENDANT, AND STONES.

CHILD’S HANDS MAKE SHADOWPLAY IN WARM MORNING LIGHT

YOUNG GIRLS TALK:

m-we have all different kinds…one we found was black with yellow spots…

j-last summer were there as much ladybugs as those flies…

m-they were crawling all over the window sills…

j-and I accidentally killed it…

m-they’re all flipped over right now…

SILOUETTE OF M ON HOSPITAL CURTAIN

M- …if you could have a ritual for death what would it be…and would it be private or shared.

P-…I think it would be shared

CAMERA TILTS TO MARIAN’S EYES…THEN TO THE LIGHT

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

Four Shadows

FAST MOVING IMAGES FROM CANADA, EGYPT, ENGLAND, RUSSIA, AUSTRALIA. EVERYDAY HOME IMAGES, SNOW & STREET SCENES.MUSICAL WOVEN SOUNDSCAPE OF POPULAR SONGS, PROCESSED SOUNDS, AND VOICES OF DIFFERENT LANGUAGES.

P- Ladybugs. They hung together like bees on honeycomb, attached to the ceiling in the hallway adjoining your room. Eventually the spread themselves through every corner of the house, as if trying to replace your presence…. I followed them closely.

FAST MOVING IMAGES AND SOUNDSCAPE CONTINUES

M- (faintly) I dreamt that…I dreamt that we decided to go back to Canada…and when I came back everything had changed, but it was still familiar…mostly I remember walking through the snow with you Phil…

FAST MOVING IMAGES AND SOUNDSCAPE CONTINUES

M- (faintly) there’s no way any of these hotel employees would ask us what we are doing because it looks like we belong…..I’m not sure how to figure all this out…..

P- Not long before you died, death scenes crept into my life. We watched a course of events that cast me as witness, each encounter making death less strange. I wondered why this was happening.

EGYPT. M IS IN FRONT OF QUEEN HATCHEPSUT’S TEMPLE

P- This is the footage we shot in the Valley of the Kings, at the Great Temple of Amun, at Horus Chapel, and at the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatchepsut. These are sacred sites and visitors are asked not to photograph on the inside. We followed this request and photograph them from the outside.

She films the broken bodies strewn on the ground, and the scratched out figure of Queen Hatchepsut, the female Pharaoh who reigned for more than 20 years. We listen to the tour guide’s version of history: Theology dictated that in order for the spirit or soul to live forever, the body, the image, or at least the name of the deceased must survive on earth. After Hatchepsut’s death a campaign was mounted against this unconventional female king whereby her name

and image were defiled, and she was physically removed from the Pharaoh lists, written out of Egyptian history. In the 19th century with the decipherment of hieroglyphics pieces of her story gradually came to light and her memory was reconstituted, but her body had been removed in antiquity and her royal tomb lays empty to this day.

M TALKS TO CAMERA IN FRONT OF PALM TREES

M-I don’t really want to say anything while you’re recording. Are you testing it out now. There is no way that any of these hotel employees would come and ask us what we were doing here because we look like we belong, sort of.

P-Why?

M-Well, because we’re white, because we have blue eyes, because we dress the way we are. Because we just look entitled in some ways. I’m not sure how to figure this out. It doesn’t fit into the categories I have to understand money and wealth and things like that. It’s just confusing.

M IS IN FRONT OF QUEEN HATCHEPSUT’S TEMPLE

P-By late afternoon on this, the first day of filming, the zoom barrel on the camera jammed. By early evening the trigger seized up and the camera became non‑operative.

Upon returning home I was anxious to see how the footage we shot in Egypt turned out. I telephoned the printer in Montreal to see if the optical work was ready. Carrick had done printing for me before and I found his work to be flawless. His wife answered the phone and she went to get him, but soon I realized there was something going on at the other end of the line. There was panic in the woman’s far off voice, and she didn’t come back to the phone so I hung up. That evening I called to see what had happened. Carrick’s wife answered and told me that he had a heart attack and passed away.

FARM BUILDINGS. CANADA. DUSK. CLOUDS PASS QUICKLY.

MUSEUM OF MOVING IMAGES. LONDON. FAST MOVING IMAGES.

P- I spent about 2 hours shooting this footage in the Museum of Moving Images in London, where, in just a very short visit you can witness what is recognized as the whole history of cinema. Blurry eyed I left the museum and got onto the bridge to cross the Thames. When I was about 1/3 across the river, a man, looked me in the eye, hopped up on the railing and jumped into the cold February water. Down through the grill of the bridge I could see his head under water and his arms limp, and he didn’t make any attempt to find the surface. A business man approached and asked if what he saw was the same thing I saw and then a woman, running from the middle of the bridge shouted that she would go to the south end to get help. Running all the way to the north end I met a police women and I asked her to radio in the tragedy…. then I saw two policemen approaching the river who told me that the report had already come in, and that a pleasure boat had picked the man up ‑ he was in the boat. They took my name and number. I would be called as a witness if the man died…. Later in the afternoon an officer left me a note at the place where I was staying: `the chap that jumped into the river is alright’ .

STILL PHOTOS OF WATERLOO BRIDGE. LONDON.

CHILD’S FINGERS AND LIGHT CARESS CRAWLING LADYBUGS

FAST MOVING IMAGES. HELSINKI, FINLAND. RUSSIAN MARKET & PHOTO EXHIBIT.

P-Sami and I hurried to catch the 8am train to Pori at the Helsinki train depot. We were travelling to the west side of Finland to present a program of Canadian and Finnish films in a small port town. While we waited for the train to leave we noticed that an elderly man behind us was in some despair. His wife was trying to find something in his pocket, perhaps his medication ‑ he was a very big man and was breathing heavily. After a few minutes a train attendant arrived and asked the woman a few questions as the old man sat shaking.

As the attendant made his way down the aisle to stop the train from leaving and call an ambulance, gears engaged and we slowly pulled away from the Helsinkistation ..it would take 7 minutes to get to the next station. The passengers returned to reading their papers, occasionally they peeked overtop the print to check the man’s condition…. eventually a voice in Finnish came onto the overhead speakers, presumably to request a doctor for the sick man. Sami said that the announcement stated that a lunch cart will soon be arriving with refreshments and sandwiches. We got up to give the woman some comfort but her attention was on her husband who was passing away before her eyes. Soon we arrived at Passila station and paramedics boarded the train, walked to where the old man lay slumped, and asked the woman a few questions. They quickly dragged his enormous body down the narrow aisle, and laid him by the door of the train. Samiwent back to find out what had happened. The man had a heart attack and was dead. As the train pulled away from the station, we watched through the window. As the train pulled away from the station, we watched through the window. The man was hoisted into the ambulance and the doors shut.

SNOW SCENES. M AND P ON A WINTER WALK. SHADOWS IN THE SNOW.

KIDS SKATING IN SUNSHINE.

SOUNDSCAPE ENDS.

BLACK SCREEN

NURSE REPORT (audio): The lung biopsy itself can lead to some collapse of the lung…this is often seen after these types of procedures, and the person is short of breath for awhile, but this does tend to resolve after a few days or so…

BREAKING WAVE IN SUPER-SLOW MOTION

TEXT SUPERIMPOSED ON WAVE:

antiseptic fictions

invade the living room

every story is ours

MUSIC: One is the loneliest number that you ever have. Two can be as bad as one it’s the loneliest number since the number one…..

` BAYWATCH’ SOAP OPERA. MAN WAITS BY WOMAN, SLEEPING IN HOSPITAL BED. HE KISSES HER. MAN CARRIES WOMAN TO BEACH.

NURSE REPORT (audio over above images): We know that the disease was extensive on x-rays as well as on the biopsy that they did…they also did echo-cardiogram. Which showed that there was fluid around the chest….around the heart area as well. Our assumption tonight is that this may have re-accumulated. We did draw back some fluid from the pericardia area. Now the echo-cardiogram showed that she did have some dysfunction of the right side of her heart and this may have been secondary to the ongoing lung problems that she was having. Over the past couple of days it seemed that she was having more and more shortness of breath….a couple reasons……

MUSIC ENDS

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

17

STILL PHOTO OF GRAMPA IN CASKET

P-Grampa died when I was in the midst of making my 1st film. As the family photographer I was asked to photograph him in the casket. I arrived before thegrievers, my uncle greeted me and showed me into the room. It was as if I was on an industrial photo assignment to film living rooms or something. When I saw him he really didn’t look like himself yet I knew that what I was doing was important for some of the family. I took 6 shots and left. So shocked with what I had done, I put the film into the freezer and left it there for almost a decade. I often wondered why my uncle never asked me for the photographs, as if the act of organizing the filming was all that was necessary. Years later I developed the film.

BRIGHT ROAD SHOTS (B&W HI-CON)

P-(softly) …17’s the number…1 + 7 is 8 …7 is doing, 8 is infinity…17’s the number….she was born on May 17 and died on November 17…(continues faintly under following narration)

P- My first encounter with death happened when I was 8. We visited Grampa’s brother, uncle Hans. He was my Godfather and I remember him from the smoke filled card games Grampa had in the rec-room where wine flowed like water and German music blared amidst the hollering. Uncle Hans had lung cancer, I was told, because he smoked. Mom took us up to the hospital and with sunshine streaming in I heard for the first time the death gargle.

P-(softly)…my dad was born April 17, my uncle was born on April 17 and my grandfather was born on April 17……my sisters were born on June 17…..1 is 1…7 is for doing and 8 is infinity…my seat on the plane was 17…(continues)

P- Aunt Katie was the widow of Uncle Hans. Every Christmas I would visit her, 1st with mom, and later on my own. She spoke little English and I spoke little German but we spoke. She was happy that I was working in film and television: ` Just the other day the TV repair man charged her a bundle for only a short visit’, so she was assured that I had chosen a lucrative career. On my last visit she complained about a nagging backache, and whispered to herself `time goes’, over and over `time goes’….A call came from my uncle in the summer, asking if I could help move Aunt Katie’s things. When I asked if she was moving he told me that she had died 3 months ago.

P-(softly) My sisters were born on June 17th, in 1953…after spreading her ashes in England, Finland and Spain, my seat number was 18… my dad was born April 17, my uncle was born on April 17 and my grandfather was born on April 17…(continues)

P- My mother carried her first pregnancy 9 months but the foetus was born dead. Apparently the doctor new that the foetus was not living weeks before the delivery, but they didn’t want to upset my mother with this terrible news. My parents had already named him Phillip after my father and grandfather. They buried him at the family plot but the priest refused to partake in the ceremony and bless the grave claiming that the foetus was born dead, and therefore the spirit had already left for limbo. My father still sites this event as the reason he stopped going to church on a regular basis. After the triplets were born my mother got pregnant again and had me. I remember sitting on grampa’s knee as he proclaimed that Phillip the third would take over the family business, but I think he really meant Phillip the fourth.

HEALTH CARE CUTS PROTESTERS IN TORONTO. DRUMMING. CHANTING.

(B&W HI-CON)

RADIO ANNOUNCER 1 (audio)- …and really that is all of it, because other then protest areas all the other major routes lighter than usual, in town we are running accident free. Help change the problems and challenges and headaches of running a business, into profits. Call AT&T Accounting Systems…

RADIO ANNOUNCER 2 (audio)- We’re just at elm Street now where a group of probably several hundred Health Care Workers are protesting outside of heQueen Elizabeth Hospital. They’ve just marched up from Front Street, they were a couple hundred when they started, other protestors have joined in, other people besides Health Care Workers, people on bicycles…

M IN FRONT OF DESK, IN STUDY. CAMERA MOVES TO WINDOW. (B&W)

P- autumn came this year in strange colours

your breath was short

a cough persisted through November

what used to go away didn’t

cancer

STILL PHOTO OF HANDS. FOOD. (B&W)

a word that stayed carefully off

your list of possible causes

cancer

arose out of your 3 hour a night sleeps

when the doctor said it might be cancer

and you should prepare yourself for surgery

you asked me to take you to the beach

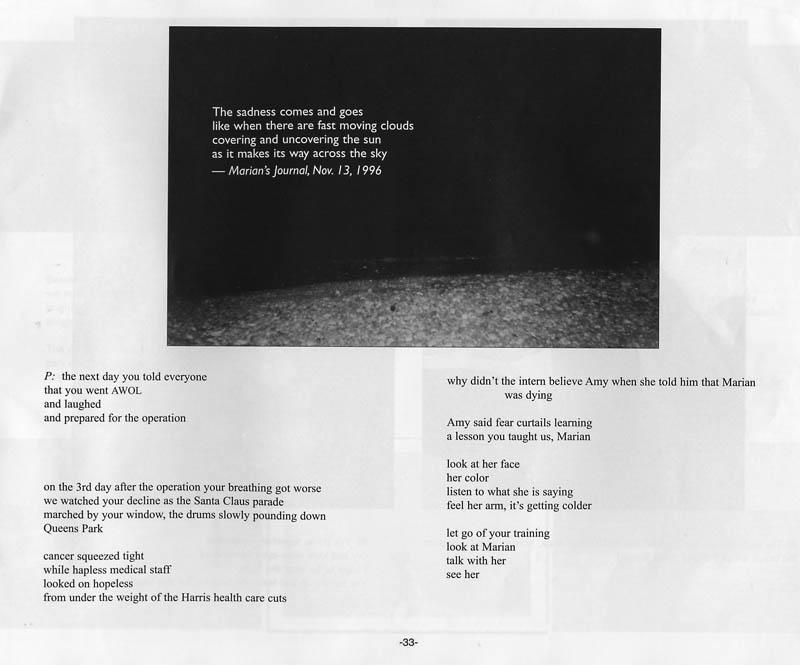

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

The sadness comes and goes

like when there are fast moving clouds

covering and uncovering the sun

as it makes its way across the sky

P- your coat covers the strapped‑in cardiograph machine

we sneak out of the hospital into the night

a dome of clouds circled above

the water was black and rippling

STILL PHOTO OF BEACH AT NIGHT (B&W)

P- you skipped a stone

and I took this picture

STILL PHOTOS, HOSPITAL (B&W)

DOCTOR (faintly)- she’s in the recovery room…..all the changes in her lungs are cancerous….it appears….

STILL PHOTOS OF SANTA CLAUS PARADE (B&W)

P- On the third day after the operation

your breathing got worst

We watched your decline

as the Santa Claus parade

marched by your window

A- He wanted to know what we expected, and I that they find out what was wrong,

because there was no explanation of why she was deteriorating. I really don’t remember what I said but he said there’s 70 patients on this floor that we are responsible for….

MOVING SLOWLY PAST HOSPITAL (B&W)

PROTEST MARCH (B&W)

A- I felt that the nurses were there..I felt that they were very good at co-operating around her care. I think Marian was relieved to have it over and, veryconnected with people.

FARMHOUSE HALLWAY, SUNLIGHT DISSIPATES (pixillation)

A- Letting herself just be cared for, so Philomene started to rub her feet with lotion and she just said it felt so good..and she washed her face with a hot wash cloth and she just loved…..

CLOSEUP OF HANDS PACKING AWAY HER BELONGINGS.

MANY LADYBUGS CRAWLING ON WINDOW

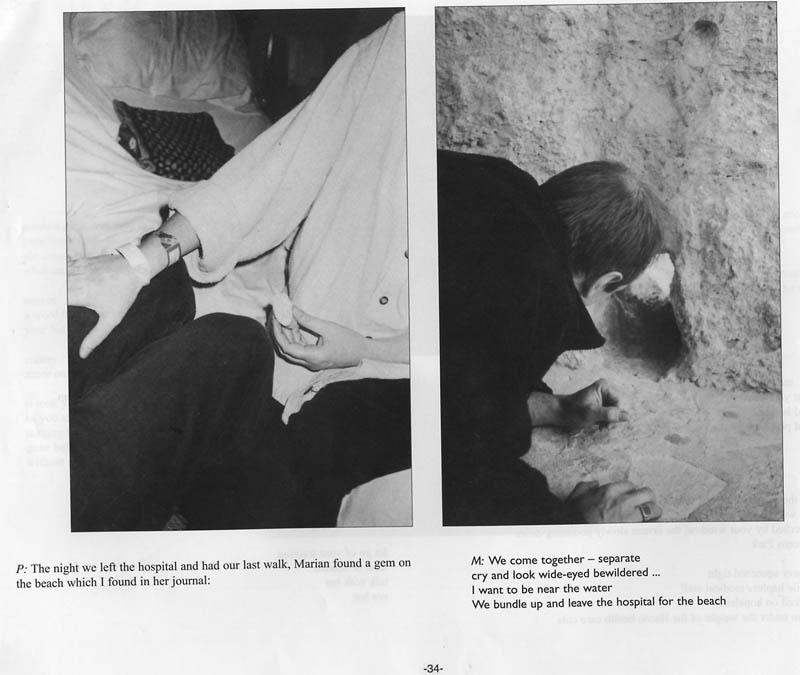

TEXT ON SCREEN (black text supered over window):

the night we had our last walk

she wrote these words

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black):

We come together ‑ separate

cry and look wide‑eyed bewildered …

I want to be near the water

We bundle up and leave the hospital for the beach

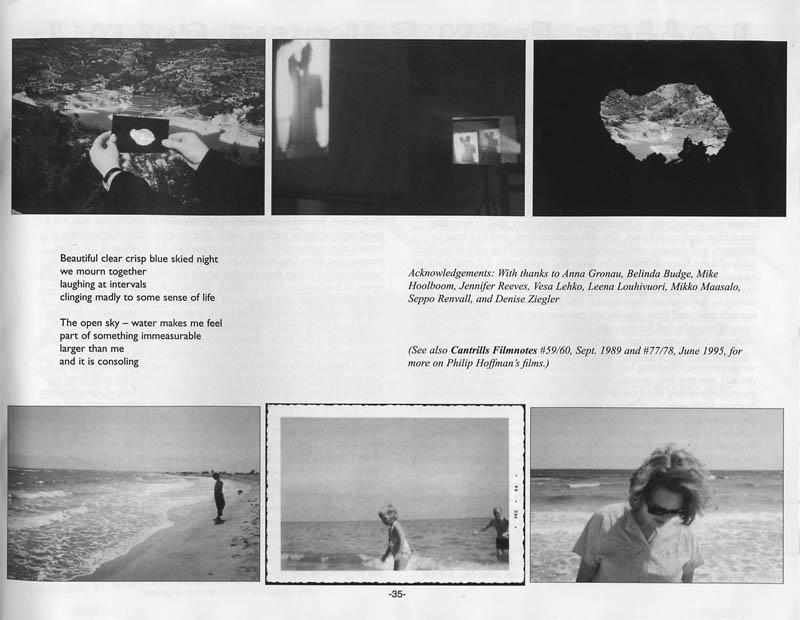

Beautiful clear crisp blue skied night

we mourn together

laughing at intervals

clinging madly to some sense of life

The open sky ‑ water makes me feel

part of something immeasurable

larger than me

and it is consoling

STILL PHOTOS OF M’S ROOM: BAGS, LILIES, WRITING, FAMILY PHOTOS,

DESK, CD (P.J. HARVEY), PHOTO OF M’S GRANDMOTHER

TEXT ON SCREEN (white on black – end credits):

A self to which it would be

worth her while to be true

Marian McMahon

May 17, 1954 – November 17, 1996

assistance in

conceptual development & editing

Anna Gronau

Philomene Hoffman

Vesa Lehko

Janine Marchessault

music composed & performmed by

Tucker Zimmerman

sound mix by

Tim Muirhead & Teresa Morrow

titles & assistance in optical printing

Marcos Arriaga

assistant picture editing

Eric Yu

kind assistance along the way

Belinda Budge

Lisa Freeman

Marg Gorrie

Mike Hoolboom

Gary Popovich

Amy Rossiter

Karyn Sandlos

Roberto Ariganello

Mike Cartmell

Ryan Feldman

Joohyun Kwon

Sarah Lightbody

Brenda Longfellow

Susan Lord

Wayne Salazar

Rick Hancox

Colleen Hoffman

Frannie Hoffman

Sue and Phil Hoffman

Graham Jackson

McMahon Family

Jeffrey Paull

Leena Louhivuori

Mikko Maasalo

Ilppo Pohjola

Perttu Rastas

Seppo Renvall

Juha Samola

Sami van Ingen

Denise Ziegler

institutional support

Graduate Programme in

Film & Video, York University

Media Arts Department

Sheridan College

Liaison of Independent Filmmakers

of Toronto (LIFT)

Helsinki Elokuvapaja

produced with the assistance of

The Canada Council

Philip Hoffman 2001

A Dream for a Requiem

Filmmaker documents pure emotion

REVIEW

WHAT THESE ASHES WANTED

Peter Vesuwalla

Philip Hoffman’s What These Ashes Wanted is one of those films that forces you to rethink the medium. There are pictures, yes, and movement, light, and sound. There is, however, no narrative, and yet there is emotion. Both of these last two points are remarkable.

To make a film that is genuinely non-narrative is no small accomplishment. At a recent exhibition of short films, I listened as budding visual artist Victoria Prince attempted to explain that there was no narrative link among the images in her latest experimental video, despite an audience member’s insistence that he had been told a story. Last year, soi-disant “guerrilla projectionists” Greg Hanec and Campbell Martin were forced to concede that people will find a story in their work provided they look hard enough: audiences tend to do so. The fact is, there is something hard-wired in the human psyche that forces us to find continuity where there is none.

What makes What These Ashes Wanted unique and interesting is Hoffman’s ability to override our inherent expectation of being told a story. We learn that his longtime partner, Marian McMahon, has died of cancer, and that the film is an expression of his grief, but that’s only what it’s about. Nothing actually happens in it, just as nothing in the physical universe happens to us while we’re sitting and reflecting on the past. It’s assembled from nostalgic pieces of video footage, bolex film, still pictures, words, music, poetry and seemingly random micro-montages that fade into obscurity like fragmented memories.

“In times of great grief, it was important to go through the motions of life,” he narrates, recalling author Henry James. “Eventually, they would become real again.”

Hoffman edits these motions together the way that Jackson Pollock paints. He expresses his grief over his lost loved one not through the images themselves, but through the physical act of filming them. The images such as an empty room, an inventory of mementoes, and a field of sunflowers, coupled with a mournful monologue and a montage of unanswered voice-mail messages, carry all the weight of emotional brush strokes. If Pollock was an “action painter,” then Hoffman, I suppose, ought to be called an “action filmmaker;” that label, however, might cause confusion. Instead, call him a documentarian of the human soul.

Philip Hoffman will be on hand to present What These Ashes Wanted, along with his pupil Jennifer Reeves’ We Are Going Home, on Thursday, May 17, (2001) at 7:30 p.m. at the Cinematheque, 100 Arthur St.

No Epitaph

by Karyn Sandlos

from Landscape with Shipwreck: The Films of Philip Hoffman ed. Hoolboom/Sandlos, YYZ/Insomniac Press, 2001

When Ann Carson writes “…death lines every moment of ordinary time” (166) she suggests that mortality resides in the quotidian details of our lives. Time, as we know it, is a progression that is measured by clocks, calendars, the passing of days, the changing of seasons. When a loved one dies, the knowledge of time passing may allow us to hover over the chaotic reckonings of the present and imagine an afterwards; a prospective view that makes the immediate impact of loss bearable. But in the midst of bereavement, ordinary time is a view from the proximate clutter of a present that can’t envision a future, a heightening of the minor drama of death that permeates the everyday. For Carson, the kind of death that “lines every moment” doesn’t quite amount to an event, to the actual fact of Death. The problem is that rather than surviving death, we live it.

What took place every day was not what happened every day. Sometimes what didn’t take place was the most important thing that happened.

— Marguerite Duras, Practicalities.

Death is a recurring fascination in Phil Hoffman’s oeuvre, a body of films that seem to rehearse a penultimate death that will take Hoffman to the outer and inner reaches of grief. In the film cycle that concludes with Kitchener-Berlin in 1990, be it the figure of a young boy lying dead on a Mexican roadside or an elephant falling at the Rotterdam Zoo, death is an indelible presence that is often left out of the frame. After 1990, by undertaking a series of collaborative works (Technilogic Ordering 1994, Sweep 1995, Destroying Angel 1998, Kokoro is for Heart 1999) and inviting audiences to order the progression of his Opening Series films (1992 ongoing project), death becomes a method in which Hoffman as maker is displaced. Phil’s latest work, What these ashes wanted, documents the death of his late partner Marian McMahon from cancer, and the film is a declaration of insurmountable grief. But the death that Hoffman has been rehearsing since assuming the role of familial custodian of memory at the age of fourteen is his own.

What these ashes wanted is populated by the familiar – even banal – images of home and family that I have come to expect from Hoffman, but here he makes use of the ordinary to evoke a profound experience of loss. Hoffman’s iconography is that of the immediate material that surrounds him: a garden alive in summer and dead in winter, the view from a hotel window, highway traffic signs, the brick wall of the farmhouse where he lives. Ashes finds a gentle rhythm in the unexceptional that acts as a refrain throughout the film, proposing a way of seeing how extraordinary loss illumines the daily practice of death-in-life. The film is not a story of surviving death, but rather, of living death, of making life hospitable to the prospect of mortality. It is through Hoffman’s carefully crafted attention to the minor details of loss that the presence of death in the ordinary fabric of life is acutely felt.

If you can read this you are standing too close.

— Epitaph for Dorothy Parker.

Bereavement has become a thriving industry in Western culture, replete with therapeutic approaches and self-help strategies that instruct on how to grieve well and for discreet periods of time. Many forms of bereavement counseling treat life after loss as a healing strategy, a way to reach toward a time when grief will be less shattering, when the pain of loss will be less present. Funerals also act as occasions for shaping and articulating grief, and for marking the distinction between the mourner and the mourned; a kind of reality check that affirms what the mind at once understands and resists knowing. And it may well be the case that loss is far too amorphous and terrifying without the containers of formality into which we are compelled to pour it. Hoffman’s project is, however, less committed to protocol and more concerned with a practice of bereavement that mixes psychic disintegration with the provisional solace taken through secular therapies or devout rituals of mourning. Early in ashes we partake of a playfully private moment shared between Phil and his late partner Marion McMahon, the first of several sequences that will draw us into the small circle of their relationship throughout the film. Heavily bundled against the cold they frolic, home movie style, in the yard outside their Mt. Forest home. The camera moves erratically across the brick wall of the farmhouse at close range; an uncomfortable proximity is felt in observance of an intimate game from which the burdens of the world seem to fall away. Phil touches the wire fence, feigns electric shock, and laughs. Filming this moment, the couple play at death while reaching for posterity – for permanence – bringing the underlying tension that haunts ashes to the surface.

People may die and be remembered, but they only disappear when they are completely forgotten, when no one ever uses their name.

— Adam Phillips, Darwin’s Worms.

It was Freud’s observation that dreams are populated by incidental images and fragments of experience from conscious life. The death of a loved one, he noted, is often obliterated from the dreamscape only to return to memory with unusual force upon waking. (78) Perhaps, then, in the midst of grief the unconscious makes itself known through a heightening of the minutae of waking life, like a long, slow swim under deep water where every movement, every sound, and every glimpse of color and light is attenuated. The irreconcilable clash between psychic longing for the lost loved one and the reality of absence is less an event than a palpable emptiness, a heightened view from the jumble of experience that has fallen out of step with the continuity of time. In ashes, the brick wall of the farmhouse contrasts the brick facade and pillars of a more monumental structure, a relic of ancient history. A figure walks slowly past an Egyptian temple, appearing, disappearing and reappearing from behind the columns. When the body is absent, this sequence implies, the shadow remains.

A person will walk through a hundred doors to carry out the whims of the dead, not realizing that he is burying himself away from the others.

— Michael Ondaatje, Anil’s Ghost.

In the days approaching her death Marian asks, “If you had to make up your own ritual for death what would it be? And would it be private, or shared?” Phil responds that it should be shared, and his tone resonates with the force of this deeply held conviction; for Phil, death is a lived practice that must necessarily be shared if one is to live at all. It is often said that funerals are for the living; but how, precisely, does ritual help us grieve and move on? With this question in mind, I often visit cemeteries and wander amidst gravestones belonging to people I have never met. Something troubles about the tone of epitaphs. The words say that the loved one is gone. Etchings in stone mark the finality of death, but they don’t account for how life is lived as the practice of death. The severing of attachment and the abruptness of absence may be life’s most shattering experience, yet loss itself has a lingering presence in life. Lovers leave, but the inevitability of death, if not desirable, is wholly enduring.

Death, although utterly unlike life, shares a skin with it.

— Ann Carson, Men In the Off Hours.

Ashes is no epitaph, no tribute to the solace of monuments or the passing of time. In his latest work, Hoffman remains in his own time, a daily practice of loss lived precariously on the margin between disintegration and ritual. A voice on Phil’s answering machine enjoins that “in times of great grief it is important to go through the motions of life until eventually they become real again.” When Phil films Marian making calls on her route as a home care nurse, he rides in the back seat and watches her face in the rear-view mirror. Caught up in the demands of the everyday and the immediacy of the task at hand, Marian thinks out loud about how peculiar it feels to provide intimate physical care to complete strangers. In illness, she observes, the body becomes public property. The conversation takes on a heightened anxiety as Marian describes the awkwardness of the situation, and her inability to talk with Phil about things she really wants to talk about while he complains about the weight of the camera. The nuances of Phil’s response are missed in an exchange in which Marian teases him for failing to appreciate the gravity of her insights. The conversation becomes a speculation on the daily minutae of loss; the disappointments, missed connections, and absences that act as small rehearsals for the larger drama of death.

Although I never met Marion McMahon, I remember her in a very particular way. I was a new graduate student waiting for a meeting in the hallway outside a professor’s office. Wanting to absorb the culture of collegiality and ideas I studied my surroundings. The walls were plastered with memoranda; posters advertising political rallies, calls for papers, and cartoon strips ¾ the clutter of academic life. What I recall most vividly is a poem that was taped to the door directly in front of me. Reading that poem, I felt a momentary break in time that I have yet to understand.

Perhaps there are no accidents. I had skimmed the eulogies on e-mail, and heard fragments of conversations in the hallways about a colleague who had passed away. She was a doctoral candidate, and she died of cancer just as her dissertation was approaching completion. The poem was written by one of Marian’s professors, but it read as if her hand was urgently tracing his words…I am still here.

She might have spoken the words, or whispered them.

It is a common clinical experience that bereaved people fear that talking about the person they have lost will dispel their contact with them.

— Adam Phillips, On Flirtation

Ashes speaks most profoundly through a story that Hoffman struggles to put to words, not only because he cannot bear to articulate his loss directly, but because language itself can only approximate the void that is absence. In ashes, loss is evoked through a reordering of referentiality, a fragmentation of the details Hoffman depends upon to order his world. A window provides the only source of light for a darkened bedroom. Although the light fluctuates, it is impossible to determine when it is morning and when it is evening. The camera hovers on time lapse. Are seasons passing, or merely hours? Formless images, shapes, and shadows are intercut with lush scenes of the garden awash with the color of emotion, with the vividness of an image one might wish to have shared with a lover. Anecdotal remnants of Marian contained in answering machine messages procure the flavor of shared lives, recount daily events, confirm appointments, and announce the birth of a baby girl.

A nurse calls, wondering what to do with a blouse left behind at the hospital.

It is possible that we have no idea what secular grief is; what grief unsanctioned by an apparently coherent symbolic system would feel like

— Adam Phillips, PromisesPromises.