by Aysegul Koc

March 2002

AK: When we say hand-made I think of the craft as well as the art using the hands and the labor involved.

PH: It’s sort of having control of the whole process and at the same time you are out of control. You have a pact with the process… with the world, that it has some say in what the film will be. You have great control in, for example, hand processing the film yourself… you don’t have to give it to the man with the white lab coat any more… and all your money along with it.

AK: When we talk about hand made film it’s not necessarily hand- processed film.

PH: No but it’s kind of a nice metaphor for it. In the hand processed film you are actually putting the film in the developer, swishing it around and putting it into different processes. What’s great about hand processed film is that you are never in total control. So it’s again being in control and at the same time relinquishing control because within a few seconds you can lose a beautiful image you love by leaving it in a chemical too long or not long enough.

AK: Has that happened to you?

PH: Oh sure, it happens all of the time. …it’s odd because that image still lives on in your memory. I have a lot of those… That beautiful image you saw in the dark room… gone… That’s life, right? These things move in time and when they’re gone they’re gone. This way you go against the idea that the film is precious and understand that the process is more important.

AK: But when you make a film you keep something as opposed to losing it?

PH: Well the film’s the residue. I’m talking what excites me. When I am not in control and I don’t know what’s going to happen and something does… that’s the fuel.

AK: Is there a project about which you would think ‘This can only be handmade’?

PH: It’s the way of living, the way of working, I think in the beginning I thought someday I’d make a big feature with real actors and all that, but then I came to realize that this is not the way that I work. The project that I am on now is called Commute. I can’t say anything useful about the film at this point. I started working on it in 1995… and in 1996 Marian died. I put Commute on the shelf. And now it resurfaced and it’s funny because now I am clear on how I want to work with it, whereas in 1995 it was vague. So I think after finishing Destroying Angel and What these ashes wanted, I was reminded of the way I want to work …it may be with some actors, or at least friends, but it will still be hand made. Well probably get a pile of people together and a pile of film and video together and start working. I’ve got the structure somewhat worked out, and the various threads of the story, but I’m not always sure what road will get me home…

AK: What exactly is hand made film? What would you consider a hand made film?

PH: I wouldn’t limit it to anything. There are many different ways.

AK: If you make a totally digital film would it still be a hand made film?

PH: I haven’t done that yet. I don’t know what that would look like. I would like to say no in some ways. And yes in other ways. I can’t really give you an answer to that. I haven’t made a completely digital film so I don’t know. But I do know that the incorporation of different elements like film footage, video footage, working on a Steenbeck, then working on a computer digitally for the editing then going back to the Steenbeck is a process I know from making What These Ashes Wanted. So because of necessity, because it’s so wonderful to work with almost seventeen, maybe twenty years, of material as I did with Ashes, on a computer, because you can call up things so fast and so easy, I’d like to think that handmade film incorporates different materials. With digital editing you have some headaches of course but… it works just like memory… boom it’s right there… I want it. In What these ashes wanted I was working on a Steenbeck and on the computer at the same time… shooting with a digital camera off the Steenbeck screen and then dumping it into the computer to work out my ideas… back and forth. It was a bit crazy because I had footage which was processed and printed way before digital editing was invented and so it wasn’t reasonable to do a keycode transfer.

I worked out my whole soundtrack, including many adjustments to the narration, on the computer which was wonderful. I found all the images I needed (super8, 16mm hand processed, still photos, video) by working out the ideas on the computer, and then I just had to master, through optical printing and video to film transfers, all of the material back to 16mm neg. In the early 1990’s I used a similar process for Chimera, using digital editing to work out the flow of images, and the frame rates, and then I went back to the optical printer and step printed the super-8 up to 16 mm negative.

AK: And you wouldn’t call that hand made?

PH: Sure, I suppose, but there is something about the physicality of hand processes that is different than mouse-made works.

AK: It wasn’t an aesthetic choice it was something that helped you work out the material.

PH: To me it was great to blend these different ways of working, these different tools. You learn something at the intersection. I think when we cross boundaries we bring what we have learned from one medium and apply it to another, and something new is discovered. Within independent film, experimental film, video art… there are many practices…ways of working. Artists find things out in their work, pass it on…this movement expands and contracts. Old movements influence new movements, new movements influence old ones…and bring it along. I remember when Jeffrey Paull was first asked to teach Photoshop, to basically move out of still film and onto computers….he was sort ordered by the administration to make the transition, and he had to teach in one of these computer labs… very un-Jeffrey Paull. So what he did was turn off all the florescent lights and bring in some nice lamps and placed them around the room… to me that’s a hand made solution. He just said: “Well wait a minute let’s not just take what’s being shoved down our throats… resist this corporate way of working…”

The term that came to being in the 60s was “living cinema” and that’s like hand-made film. In hand made making you don’t light the breakfast table… you film your loved ones, or they film you on the spot… you don’t make them pour the orange juice again… and again… and if you miss a shot, you get the next thing that comes along… light glistens off the apples on the table… the kids playing…

AK: Is this not more possible with the video camera? More people have access to it now and can do amateur work.

PH: I would say that it is but it’s different because there is usually the sound attached whereas with a Bolex it’s always just the image. In video it’s, ‘What are you doing with that toy, Jessie?’ The words become important so there’s a difference and I don’t think it’s always better though it can be… it’s how one works with it. Access is great of course, yes. For me it has less to do with technology and more about working ‘from your hand’…working ‘from your heart.’

AK: What about all the difference between mouse and hand?

PH: We have to develop ways to work with computers that isn’t so draining. For myself I find it just as exciting but sometimes I get a hollow feeling when I sit in front of a computer for ten hours whereas I just feel exhausted sitting in front of a Steenbeck… to me there is a difference. We have to work out how to get the best out of the various technologies and practices…. My body of work contains video all the way through, though it often ends on film but I try to use video and film for good purposes. So I think that integration is sort of happening and will continue to. You can take ‘a hand made perspective’ on it.

AK: When you use mixed media video, film, Steenbeck, media 100 AVID…. Instead of the actual process it shifts to a mentality.

PH: Let me ask you. You started shooting film and fell in love with it. So tell me why.

AK: It smells, it’s the very basic things. The way you like food or sex, it’s the same thing. Like sweating over the dark bag. Dealing with film macaroni when you open the magazine lid, the reward of capturing moments.

PH: (laughs) Yeah it’s good. We make a trade off. We get this wonderful memory machine, the computer. We use it. But we don’t give up the hand made philosophy and the hand made techniques you know.

AK: What you are doing, mixed media, is very important. Is this unavoidable in the future? Is this the path your work is going to take? Somehow it makes our life easy, you’re sitting in front of a computer now. You can’t go back?

PH: You hate it and you love it. I hate it and I love it. I think it’s a matter of how to make it palatable. You have to say ‘enough is enough.’ It’s like too much sugar. It’s seductive. It’s become this octopus with arms all around you, this open access. I get hundreds of e-mails a week from students, admin, strangers, filmmakers…. It’s all wide open. I think in the next five years I will be working out how to deal with this incredible communication overload. Everybody needs to do that or else there’s going to be a lot of sick people around.

AK: Is it why there is so much interest in the projects like film farm?

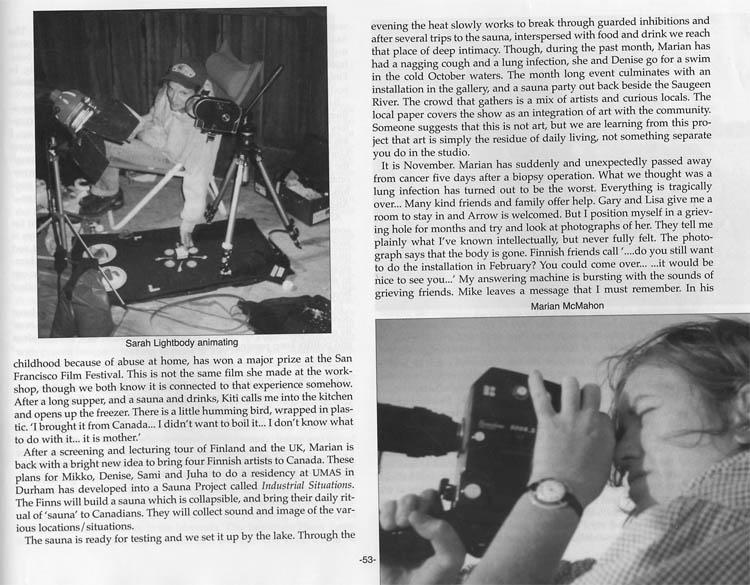

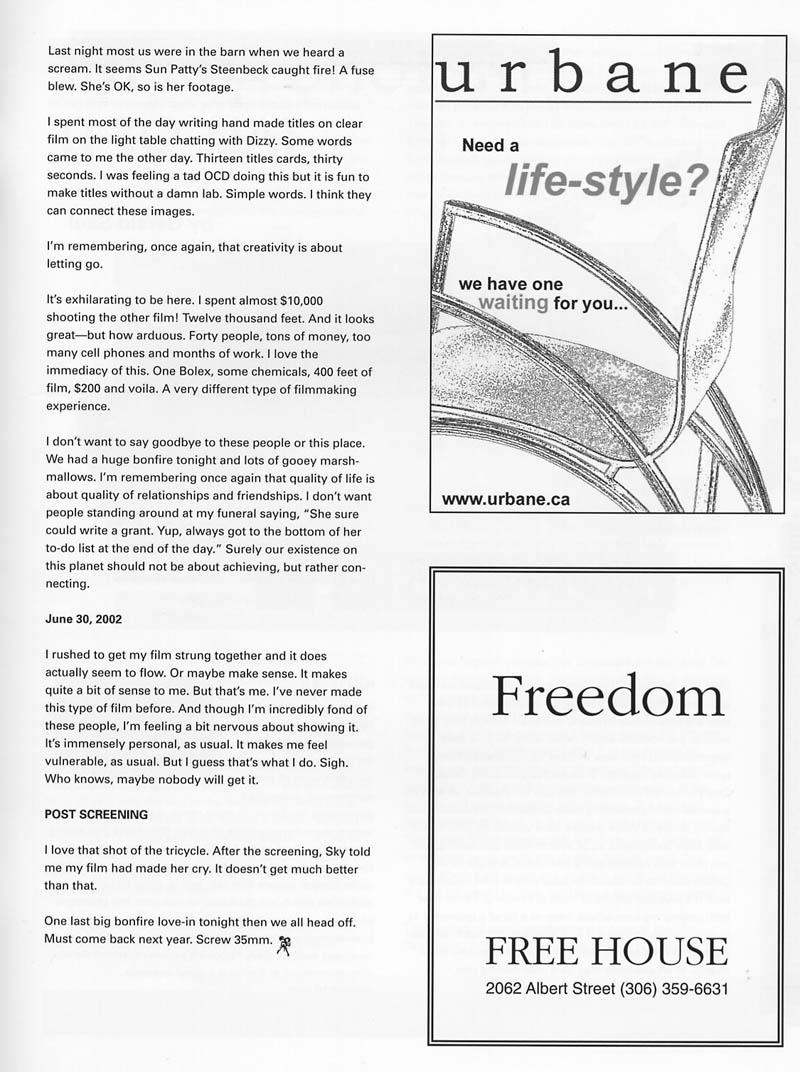

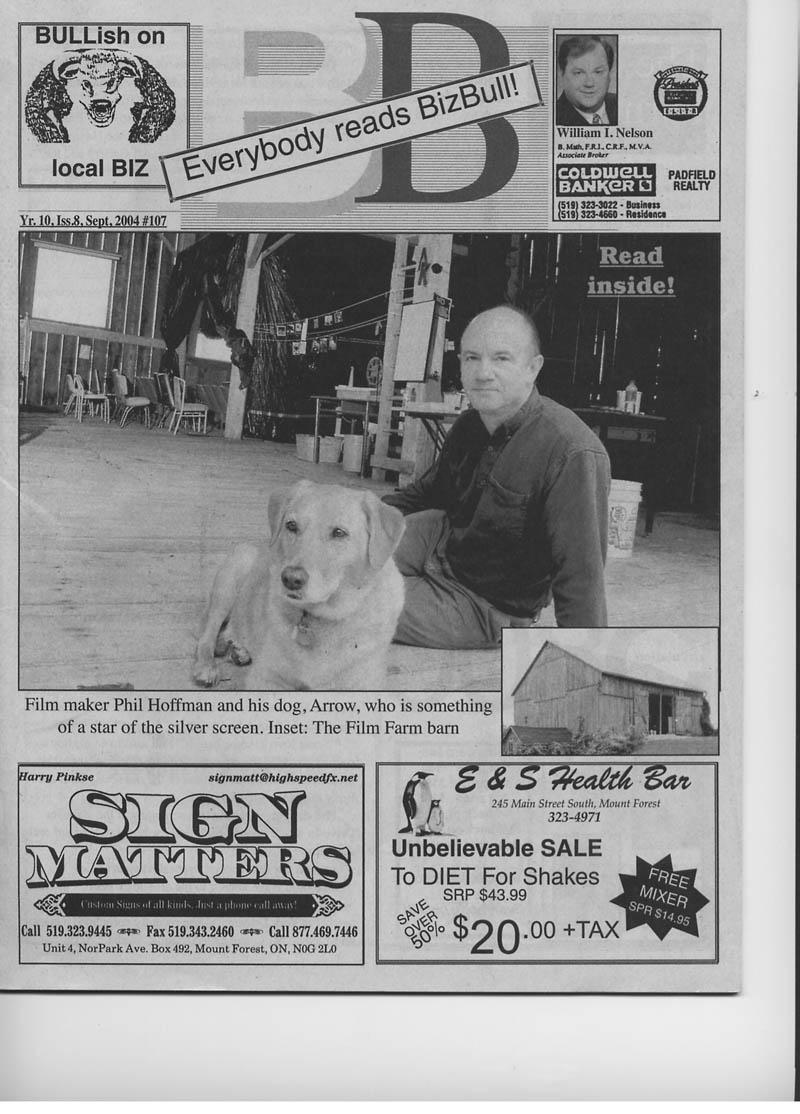

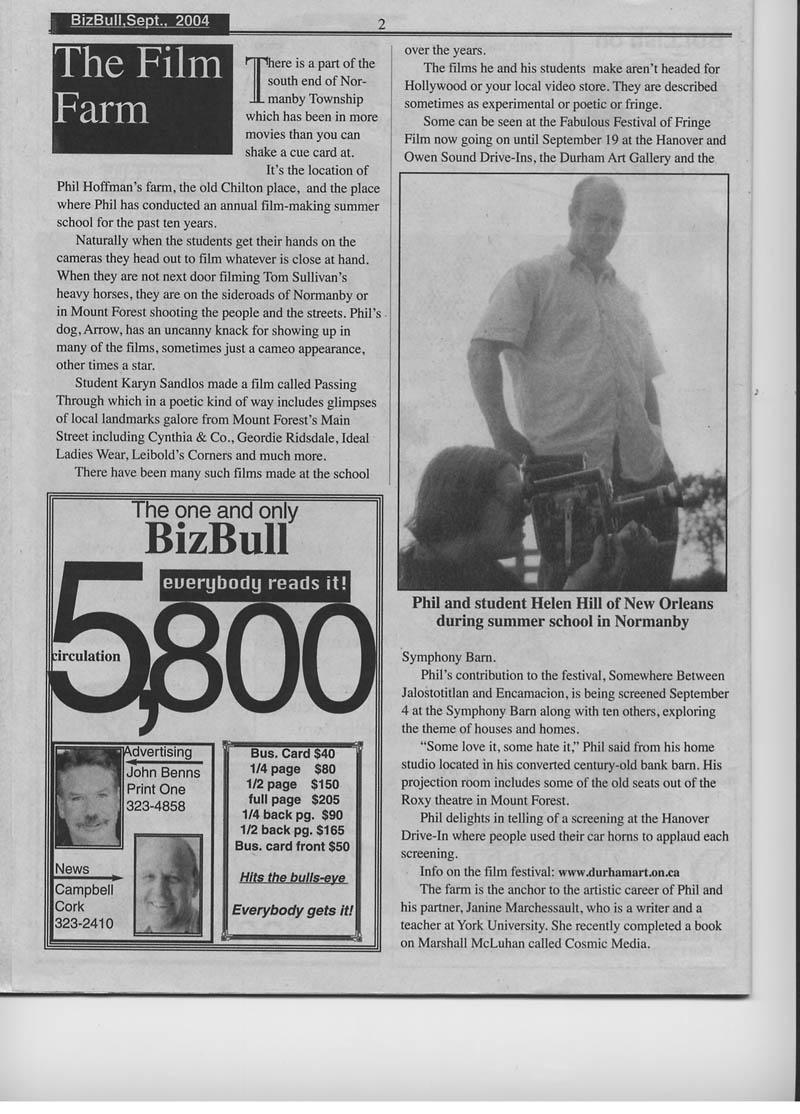

PH: First off it’s a retreat… you have people staying together, talking to each other about film & ideas… for a full week… quite intense… we create a very powerful energy.

AK: Don’t they come to the farm to learn hand made?

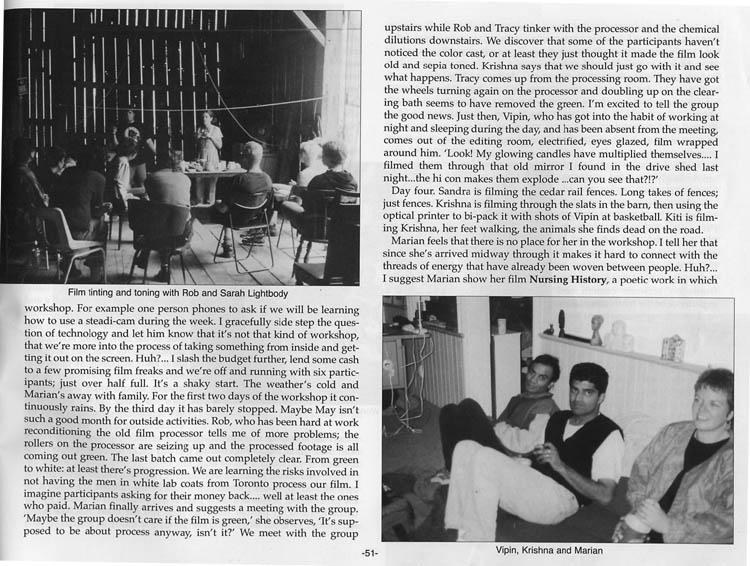

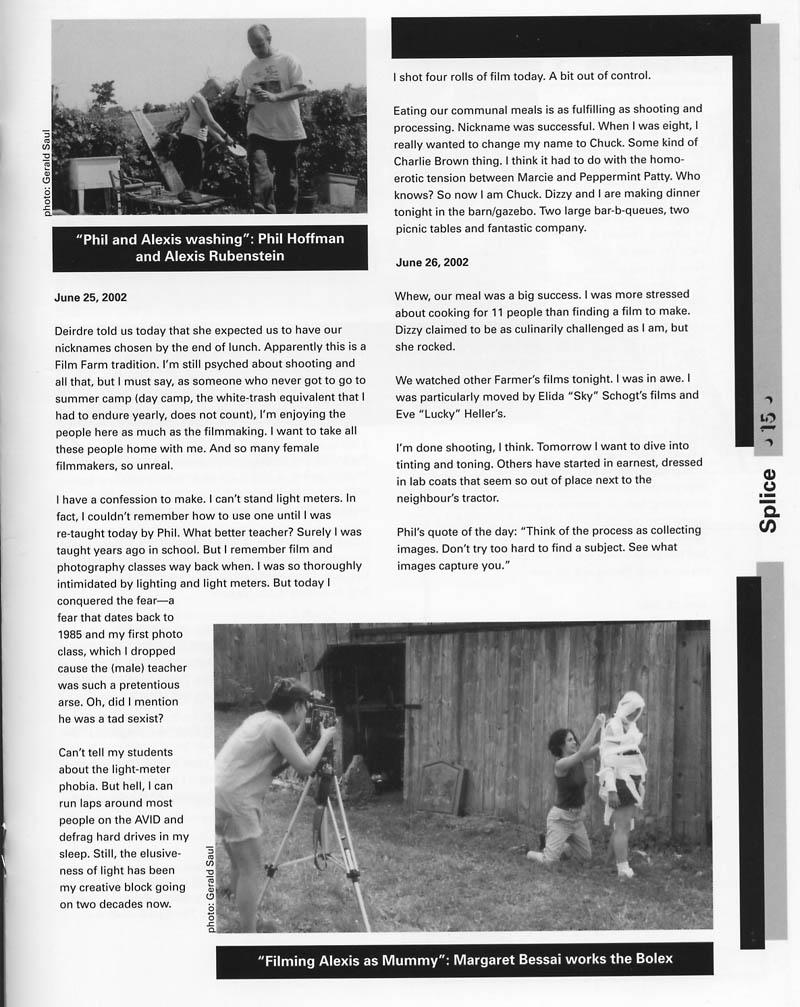

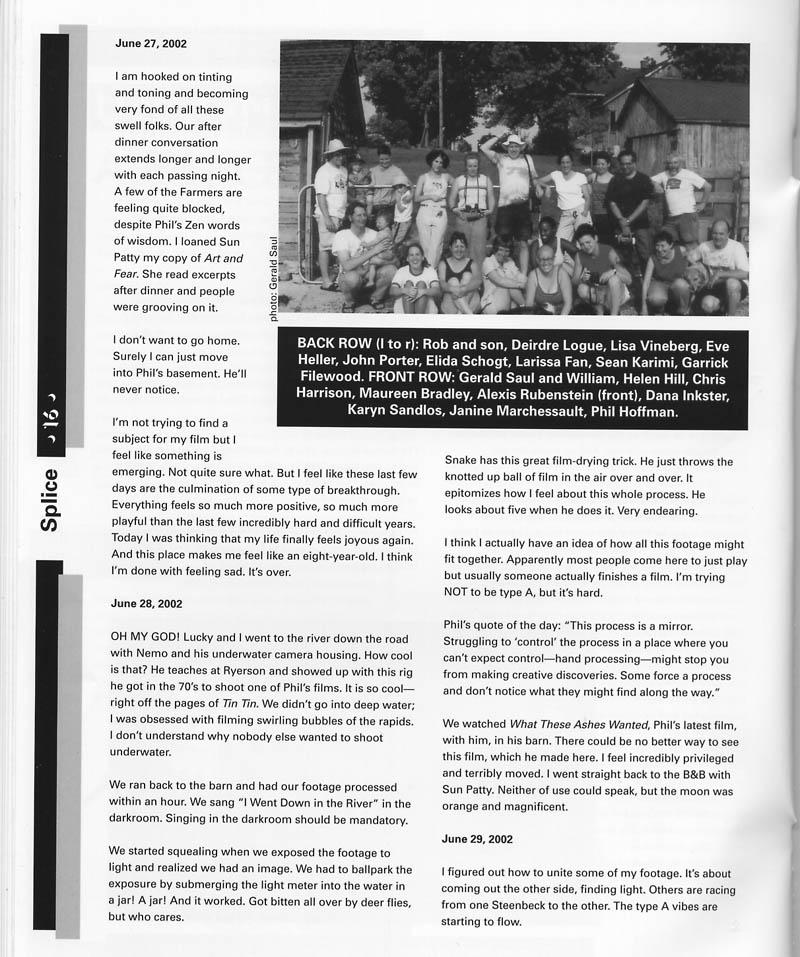

PH: Yeah, but they could do it in LIFT (Liaison of Independent Filmmakers of Toronto) workshops as well. I think it’s something else… a few years after the film farm began, some guys from a television station asked if they could come and follow the workshop for the week, for some kind of cable broadcast… and I said no because the taping process …the crew and all that… would create a rupture in the space we try to make… the workshop would become something else so I try to protect this little thing that’s kind of grown, but is still pretty small and intimate… the problem that we get into at film schools is that everything needs to be big… We need the newest technology so we need more money….so we need more students… so we get government cuts… and we can’t run this big thing that’s been created. It gets out of control. So we started the Film Farm, tore away some of that film school infrastructure so we could get back to the things we like about working in this art form The film farm is democratic… here, Karyn Sandlos and Deirdre Logue do the tinting and toning cooking show.

AK: Do they call it that?

PH: That’s what I call it.

AK: How did you start making hand made films?

PH: It came out of photography. I had a dark room.

AK: So you were already close to the chemistry.

PH: I was close to the idea of an image coming out of nothing. It’s magic you know. It’s now you see now you don’t. The image appears in the developer and that’s enough for me. I can stop right there. That moment when something is appearing you get a kick. That’s what I try to maintain in filmmaking. I don’t get a kick out of it as much when I know what’s going to happen.

AK: And video in a sense is very predictable?

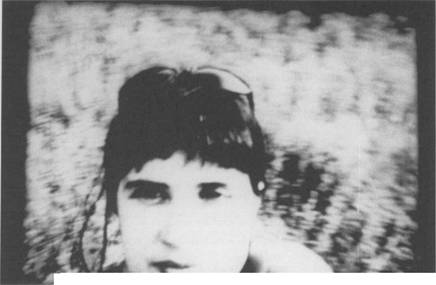

PH: With video you get these moments where there is interactions with people. You get sound and you get people saying beautiful things. That’s why I use video in my films. In What These Ashes Wanted Marian is in the car talking about what she just saw behind the closed doors along the roadway during her visiting nurse calls… There is no way I could have received those moments, in the same way, with a film camera. I would have controlled it, if I used the film image, without sound. She is kind of in charge there, not me, even though I might have thought I was in charge. She is performing, and she turns things around by making me look at what I’m doing.

AK: Directly addressing you or ignoring you or looking at the traffic.

PH: Yeah, and even so much as saying, ‘This really feels uncomfortable, you’re pointing the camera at me.’ Suddenly the lens shatters because it makes you aware of the apparatus, makes you look at the construction… the filming process. Marian was so good at that, always stepping outside of the frame. That’s fantastic… I was just learning from her in some ways.

AK: It’s a process of learning handmade film… I just want to know more about the limitations and the freeing aspects of the hand-made. It sounds good to make a hand-made film but it must have limitations.

PH: It’s hard… maybe harder than working with a script. I collect images, over a long period of time, and then I have to figure out how all the pieces fit together. It’s a long process, What These Ashes Wanted took nearly five years, but actually I used footage dating back almost 20 years. passing through took six years. Road Ended at the Beach took seven years. Chimera took six years. I usually need time to think about it.

AK: One more thing, the hand made films (I’ve seen) tend to be experimental, do they always go together?

PH: There are some filmmakers working hand made and their films are more narrative. They’re working with actors. It depends… I think anything can be hand made. It’s just that hand-made is likely not to be on TV, although you say Carolynne Hew’s Swell was on TV… that’s was shot at the Film Farm… great! Just think …a hand-made film channel…

AK: (laughs)

PH: Put that at the end… ok?

AK: But what if next year at the film farm there are TV cameras wanting to watch you twenty-four hours…

PH: I won’t let them in. They have to stay at Tim Horton’s in town …they have to wait there….and we will make daily appearances when we come for coffee….(laugh) But anyway, we protect what we have. It’s really a matter of how you work and good work comes out of that. You work in a way so that you are still having fun…. you’re with people you want to be with… if the pressure gets so great that you’re not having fun, that’s not hand-made film. (laughs). Actually, it doesn’t always have to be fun but you’re learning and you’re sharing these things with people.